Museum of Modern Art and Western Antiquities, Section II Department of Carving and Modeling: Form and Volume

Department of Carving and Modeling: Form and Volume is the third and last chapter in the series of exhibitions curated by Jens Hoffmann, aimed to be displayed at the fictional institution of the Museum of Modern Art and Western Antiquities Section II. This final exhibition takes place within the Cristina Guerra gallery in Lisbon. The exhibition stages an investigation into contemporary sculpture, showing how quickly the medium has changed over the last years.

Deconstructing the traditional idea of sculpture as a three-dimensional object, Jens Hoffmann invited sixty artists to give birth to an exhibition that perfectly fits with the expanded notion of the sculpture as theorised by Rosalind Krauss. In fact, the exhibition is composed of everyday objects, paintings, text-based pieces, textiles, rubbings, ceramics and so on.

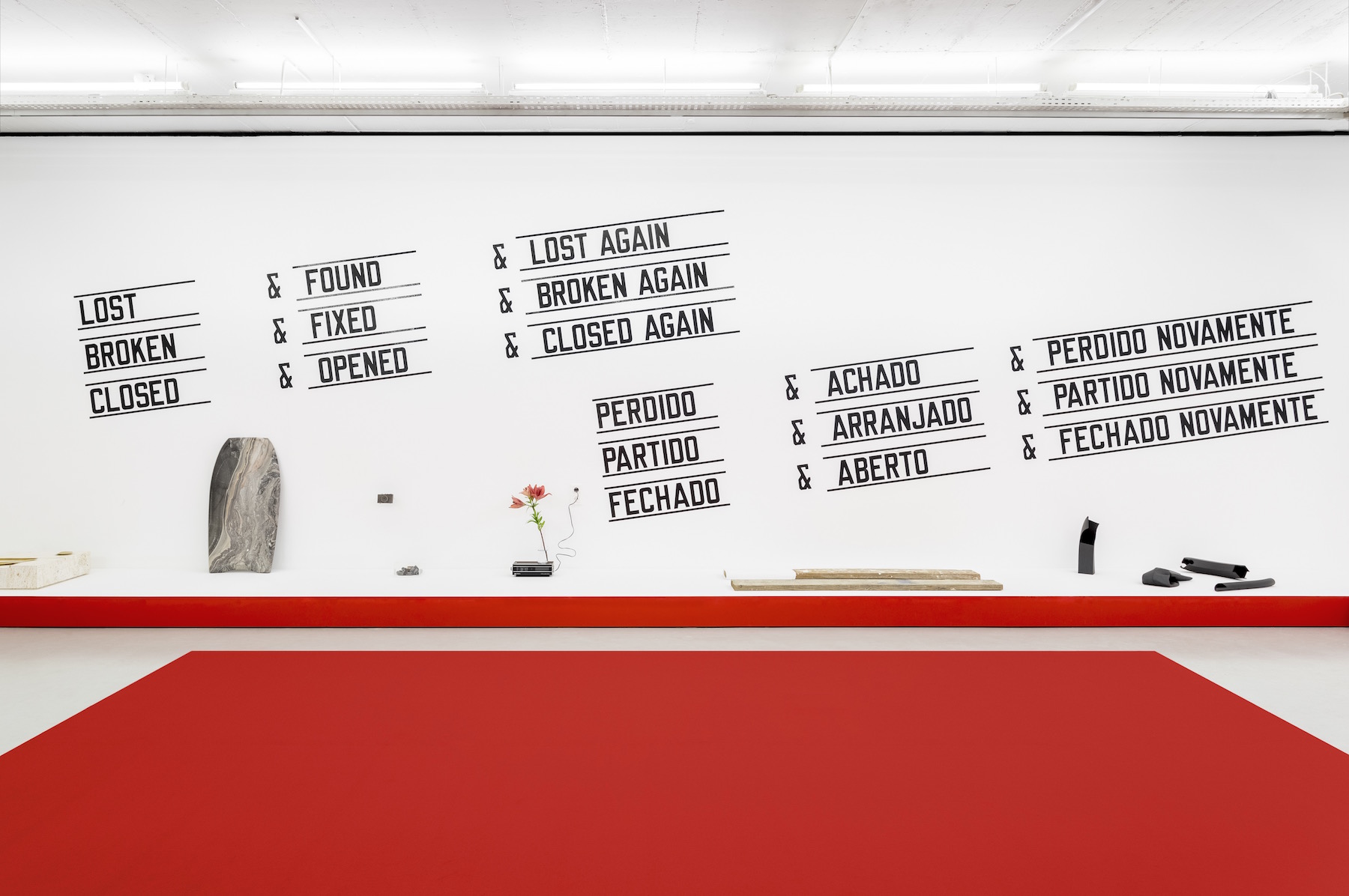

Trying to create an order and a sort of categorisation system, the Department of Carving and Modelling Section II shows its best museal side. The display conceived by the curator is a set of structures which are clearly influenced by the most traditional methods of showing artefacts within an archaeological or ethnographic museum.

A massive red wall receives the visitors, and golden letters announce the name of the exhibition. On entering the gallery everything's made to look institutional.

All the sculptures are placed upon a long unique platform that runs around all the walls of the gallery.

The unusual high density of artworks is aimed to overwhelm the visitor, while simultaneously making it possible to clearly recognise each work. Each sculpture is brutally abstracted from the context of their creation and, as if inside a museum, they are completely crystallized in an eternal present, becoming similar to relics of an ancient and remote age.

In this environment some artworks, no matter which shape or size, are placed directly on the platform, like Looking for John Connor (2019) by the American artist Kathryn Andrews; some of them are hung to the walls like Soft Marlboro Cigarette Box (2019) by Al Freeman; others are displayed with different supporting structures like Atlas (2018) by Marlon de Azambuja, exhibited in a glass cabinet with replica structures from the Museum of Modern Art of New York.

Any kind of display, from the simplest to the most complex one, tries to shift the visitor’s point of view to an undefined future. Here, the viewer is not anymore in the presence of a contemporary art exhibition, but in what resembles an archaeological site full of rubble.

This same strategy was used in the previous two chapters as Department of Pigments on Surface Section III: Very Abstract and Hyper Figurative, at the Thomas Dane Gallery in 2007, appeared as an overview of recent paintings. The second one, Department of Light Recording Section IV: Lens Drawings, took place at Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris in 2013 in what pretended to be an investigation of the photographic medium.

Forcing into these exhibitions the idea of institutional display, the result is a device that gives the public the possibility of critical distance, creating a history of the contemporary era.

Structuring his museum, Jens Hoffmann has always underlined the link to the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, one of the most emblematic “fictional museums” opened in 1968 by Marcel Broodthaers. Inspired by the political protests, within a climate of scepticism of the social and political system, the Broodthaers museum was aimed to question the internal mechanisms of institutions of the arts; the Belgian artist let the museum structure collapse through a plenitude of images and contents. Bringing some aspects of everyday life inside the museum he avoided the objectivity of scientific categorisation. Creating his own museums, he arrogated to himself the right to determine what is art and what is not. In this way, he literally tried to extend the art field.

However, the Broodthaers’ legacy is more present in artistic operations which focuses on the expansion of the notion of art. Such projects include: Cátedra Arte de Conducta (Behavior Art School) (2002 – 2009) by the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera, who in the lack of existing academic centres in Cuba structured an artistic project as a real academy of fine arts; or like The Incest Museum (2008 – ongoing) by Simon Fujiwara, an architectural/performative project composed of a fictive institution that explores the erotic origins of humankind, proposing incest as part of humankind’s ancestry.

Unlike these examples, the Jens Hoffmann museum seems to operate in the opposite way. Exasperating the institutional dynamics, bringing them into commercial galleries, he proclaims the artworks’ death, transforming them into archaeological artefacts. Joining the heritage of the institutional critique, the Museum of Modern Art and Western Antiquities is also an open question of the Modernist idea of linear progress.

Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art

Vincenzo Di Marino is an italian curator based in Lisbon. He obtained his MFA in Curatorial Studies at Naba in Milan. In 2018 he co-founded the curatorial research project Bite The Saurus based in Naples. In the last few years he worked with Umberto Di Marino gallery, Naples; Prada Foundation, Milan and Madre Museum, Naples.

Department of Carving and Modeling: Form and Volume é o terceiro e último capítulo da série de três exposições com curadoria de Jens Hoffmann, concebidas para a instituição fictícia — Museum of Modern Art and Western Antiquities Section II [Museu de Arte Moderna e Antiguidades Ocidentais Secção II]. A exposição final tem lugar na galeria Cristina Guerra, em Lisboa, onde se encena uma investigação sobre a escultura contemporânea, mostrando de que forma este medium foi-se modificando ao longo dos últimos anos.

Desconstruindo a ideia tradicional da escultura enquanto objecto tridimensional, Jens Hoffmann escolheu sessenta artistas para criar uma exposição que encaixa perfeitamente na noção de campo expandido da escultura tal como foi teorizada por Rosalind Krauss. A exposição é composta por objectos do quotidiano, pinturas, têxteis, cerâmica, entre outros.

Tentando criar uma ordem e uma espécie de sistema de categorização, Department of Carving and Modelling apela à sua componente mais museal. A exposição consiste num conjunto de estruturas que são claramente influenciadas pelos métodos mais tradicionais de exibição de artefactos no contexto de um museu arqueológico ou etnográfico.

Uma imensa parede vermelha recebe os visitantes e letras douradas anunciam o nome da exposição. Ao entrar na galeria percebemos que tudo foi pensado para parecer institucional.

Todas as esculturas estão colocadas em cima de uma longa plataforma que percorre todas as paredes da galeria. A invulgar densidade de obras pretende arrebatar o visitante, permitindo simultaneamente o simples reconhecimento das peças. Cada escultura é abstraída do contexto da sua criação e, como se estivessem expostas num museu, encontram-se completamente cristalizadas num eterno presente, tornando-se semelhantes a relíquias de uma época antiga e remota.

Neste ambiente, algumas peças, independentemente da sua forma ou tamanho, são colocadas directamente na plataforma, como Looking for John Connor (2019) da artista norte-americana Kathryn Andrews; ou penduradas nas paredes como Soft Marlboro Cigarette Box (2019) de Al Freeman; outras são exibidas com diferentes estruturas de suporte como Atlas (2018) de Marlon de Azambuja, exibida num armário de vidro com estruturas réplicas do MoMA: Museu de Arte Moderna de Nova Iorque.

Qualquer display, do mais simples ao mais complexo, tenta deslocar o ponto de vista do visitante para um futuro indefinido. Aqui, quem vê não está já na presença de uma exposição de arte contemporânea, mas sim no que se assemelha a um espaço arqueológico cheio de artefactos.

Esta mesma estratégia foi utilizada nos dois capítulos anteriores — Department of Pigments on Surface Section III: Very Abstract and Hyper Figurative, apresentado na Thomas Dane Gallery, em 2007, como uma panorâmica de reflexão sobre a pintura recente. O segundo, Department of Light Recording Section IV: Lens Drawings teve lugar na Marian Goodman Gallery, em Paris em 2013, no que simulava ser uma investigação sobre o medium da fotografia. Ao impor, nestas exposições, um modelo institucional o resultado revela um dispositivo que permite ao público a possibilidade de distância crítica, criando uma história da contemporaneidade.

Jens Hoffmann sublinhou sempre a ligação deste seu modelo de museu ao Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, um dos mais emblemáticos "museus fictícios" aberto em 1968 por Marcel Broodthaers. Inspirado por protestos políticos, num clima de cepticismo relativamente ao sistema social e político, o museu Broodthaers tinha como objectivo questionar os mecanismos internos das instituições artísticas. Trazendo alguns aspectos do quotidiano para dentro do museu, evitou a objectividade da categorização científica. E ao criar o seu próprio museu, arrogou para si próprio o direito de determinar o que é arte e o que não é, expandindo, desta forma, o campo artístico.

Contudo, o legado de Broodthaers está mais presente em operações artísticas que se centram na expansão da noção de arte. Tais projectos incluem: Cátedra Arte de Conducta (2002-2009) da artista cubana Tania Bruguera, que devido à falta de centros académicos em Cuba concebeu um projecto artístico na forma de uma academia de Belas-Artes; ou como The Incest Museum (2008-presente) de Simon Fujiwara, um projecto arquitectónico/performativo composto por uma instituição fictícia que explora as origens eróticas da humanidade, propondo o incesto enquanto parte integrante da ancestralidade da espécie humana.

Ao contrário destes exemplos, o museu Jens Hoffmann parece operar de forma inversa. Ao provocar e promover um discurso institucional no contexto de uma galeria comercial, proclama a morte da obra de arte, transformando-a em artefactos arqueológicos. Juntando-se à herança da crítica institucional, o Museum of Modern Art and Western Antiquities é também uma indagação à ideia Modernista de progresso linear.

Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art

Vincenzo Di Marino é um curador Italiano sediado em Lisboa. Em 2018, co-fundou o projecto curatorial Bite The Saurus. Recentemente, colaborou com a Galeria Umberto Di Marino, Nápoles; Fundação Prada, Milão; Museu Madre, Nápoles.

Museum of Modern Art and Western Antiquities, Section II Department of Carving and Modeling: Form and Volume . Vistas da exposição Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art. Fotos: © Vasco Stocker Vilhena. Cortesia de Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art.