Diogo Evangelista: Íris

What an invariably rewarding thing it is to follow an artist's career and observe its different stages. A particular trait may seem to recur at times, establishing a sort of thematic or formal constancy; then, a change of direction might take place as a new course is outlined. Indeed, aren't all artistic biographies made of such changes? Indissociable from such an exercise, acting as its opposite, another of a no less stimulating nature emerges: that of discovering or identifying a sensibility or a certain making which, though intangible, might interconnect all those moments: a longitudinal, subterranean background.

In that respect, Diogo Evangelista's trajectory is an exemplary one. In his first exhibitions, especially the Galeria 111 ones (2009 and 2011), the ontology of the pictorial image was a relevant question. By way of various interventions and a rather sharp approach (often a fascinated one as well), Evangelista enquired into pictorial experience in a world congested with reproduction and digital dissemination of images. Painting emerged as a potential, rather than as a material. However, the pictorial question was not an autonomous matter; instead, it was part of a "method" that can be characterised by the following elements: experimentation, transformation, dehierarchisation (as seen in his appropriation of images), and modification of states of perception. In subsequent exhibitions and projects (for example, at Galeria Quadrum, 2012), the artist would not do away with such elements: he re-elaborated and renewed them, as he turned his attention to the relationships between technology, art, and science.

By deploying the free, seductive imagination inherent in the fiction of art and in the art of fiction, Evangelista initiated a visual, aesthetic, or conceptual enquiry into the concepts of human, non-human, or machine, while also interpreting the possible meanings of terrestrial or extra-terrestrial life.

It is thus within this framework that the exhibition Íris emerges, at Centro Cultural Brotéria, Lisbon. Featuring but unseen works, a certain visual, perhaps pop exuberance promptly stands out therein. This has been a steadfast, characteristic aspect of Diogo Evangelista's body of work. In other words, there is in it a (sensorial and sensuous) pleasure that is communicated by the artist (via his making) and experienced by the viewer. Does a recurring element that would allow for identifying a work, if provisionally, transpire from such? Perhaps; but let us continue. At the centre of the room, the light sculpture The One and the Others both illuminates and is illuminated. Made up of nine lit ellipses, it alludes to Evangelista's drawings from the Spiritual Automata series, first presented in 2019, as it transcends them as a physical extension. Three-dimensional and suspended in space, they create a relationship between optical, chromatic, and luminous elements. Blue, red, and white hues shine intensely and delicately, in curved, whirling shapes that intersect, imbricate, and cut across one another. In metaphorical terms, this system of luminous, circular shapes can be interpreted as an image of the interdependence that governs human and (some) animal relationships. As for the experiential aspect of it, on the other hand, when seen from different angles, a sculpture is never the same sculpture while remaining the same sculpture. Under our gaze, it moves without moving. Such a (faux) movement representationally alludes to a set of spatial orbits, to a hypothetical solar system that has yet to be discovered, comprised of new relationships, subjectivities, and alterities. Evangelista's work rests on projective eagerness; yet, a closer look upon the piece unveils the flaccid presence of cables: against the lighting, they reveal traces of handwork. Though the artist gazes at space, his making remains terrestrial.

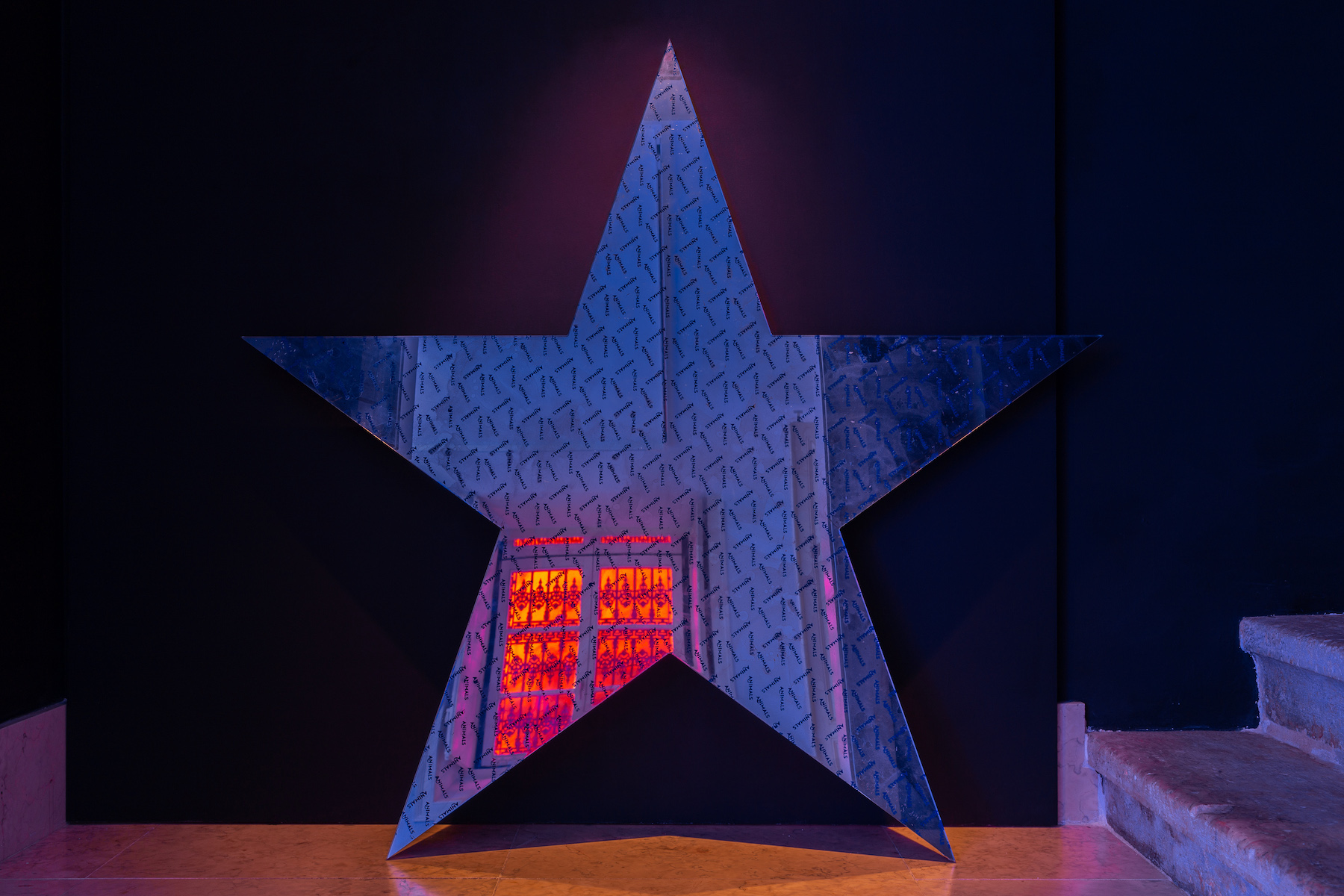

It has been written that the modification of perceptual experience has been a constituent element of Diogo Evangelista's work. In Íris, deploying the orange vinyl filter he had used in the exhibition Red Heads, in 2009, the artist sealed the venue's windows and passageways (with the exception of the door). This intervention entirely alters the viewer's perception of the outside world, rendering the latter a plastic, visual unreality. An iron grille becomes a drawing, a hallway is given a pictorial quality, the street outside conceivably develops into some Martian landscape. Such is the ambience that hosts the painting/object Echo, in which Evangelista redeploys the pentagram symbol he had already used in Blind Faith, in 2020, curated by Nuno Crespo at the Católica Porto School of Arts. As on that occasion, in Íris the artist has deposited chromium and pigments on acrylic glass, thus turning the aforementioned pentagon into a mirror in which the visitors, from a certain distance, can see their reflection. Yet, this time, they are not alone. A word multiplies across the mirrored surface into a pattern: animal. The graphics are strangely familiar—the printed word is a reproduction from Disney wrapping paper—and irony is thus ushered in. Against the standardising force of such a gargantuan company, an unexpected dialectic is produced between the animalisation of human beings and the anthropomorphisation of animals.

The question of being rearises more poetically in the "animation" from which the exhibition borrows its title. A 23-painting series, it portrays the life of an Iris germanica specimen before it began to blossom. This flower species is a motif in Vincent van Gogh's painting, and Diogo Evangelista himself had already explored the botanical motif in his An argument against anti-realism, shown at Galeria Quadrum; yet, what we see here is a painting in motion. Each image represents a different moment of the same being, or rather a different apparition of the same being in time. In some way, Evangelista seems to retrieve the this is what happened of the photographic image in an unusual, almost impossible fashion: by using painting. Let us note that Iris germanica is associated with inter-world relationality or communication; in this exhibition, thus, it semantically extrapolates a non-human world from a human one, the artificial from the natural, the photographic from the pictorial, eternity from evanescence—and the other way around, too, seemingly.

Such a movement of life rendered eternal by painting eventually meets a blind viewer in the sculpture Inflated With a Fluid: the bust of an anthropomorphic figure, or rather the representation of the fossilised, dead face of a humanoid being. Diogo Evangelista tells us nothing about this sculpture, which stands on a plinth. His gesture is a simple, silent one: it allows us to encounter the fragile monstrosity of the other, in the honourable presence of some physiognomy, such as the plant, that has been touched by time.

Other Articles on the Artist:

José Marmeleira. Master in Comunicação, Cultura e Tecnologias da Informação (ISCTE), he is a grant holder from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) and a PhD candidate in Filosofia da Ciência, Tecnologia, Arte e Sociedade at Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, in the context of which he is currently writing a dissertation on Hannah Arendt's thinking on art and culture. He is also an independent journalist and cultural critic for several publications (Público supplement Ípsilon, Contemporânea, and Ler).

Translated from portuguese by Diogo Montenegro.

Diogo Evangelista: Íris. Exhibition views at Centro Cultural Brotéria, Lisboa, 2021. Photography: Bruno Lopes. Cortesy of the artist and Brotéria.