Pedro Neves Marques: Corpos Medievais

A vegan falls ill after being tempted into trying lab-grown meat as an ethical source of protein. A spectral Lana Del Rey cover scores an abstracted narrative about a gay couple trying to get pregnant via biotech. A short story about four friends—a hetero and homosexual couple—expands that narrative into a relational drama dealing with broody 30-somethings and cis-male ovarian implants, against a backdrop of medical innovation and increasing male infertility, before reaching a Bartelby-esque conclusion. Thirteen shots of the same hand-held smartphone present us with 13 different on-screen poems. Whilst in the corner nanobots from the future kill off Sigmund Freud before he’s had a chance to develop his psychoanalytical framework.

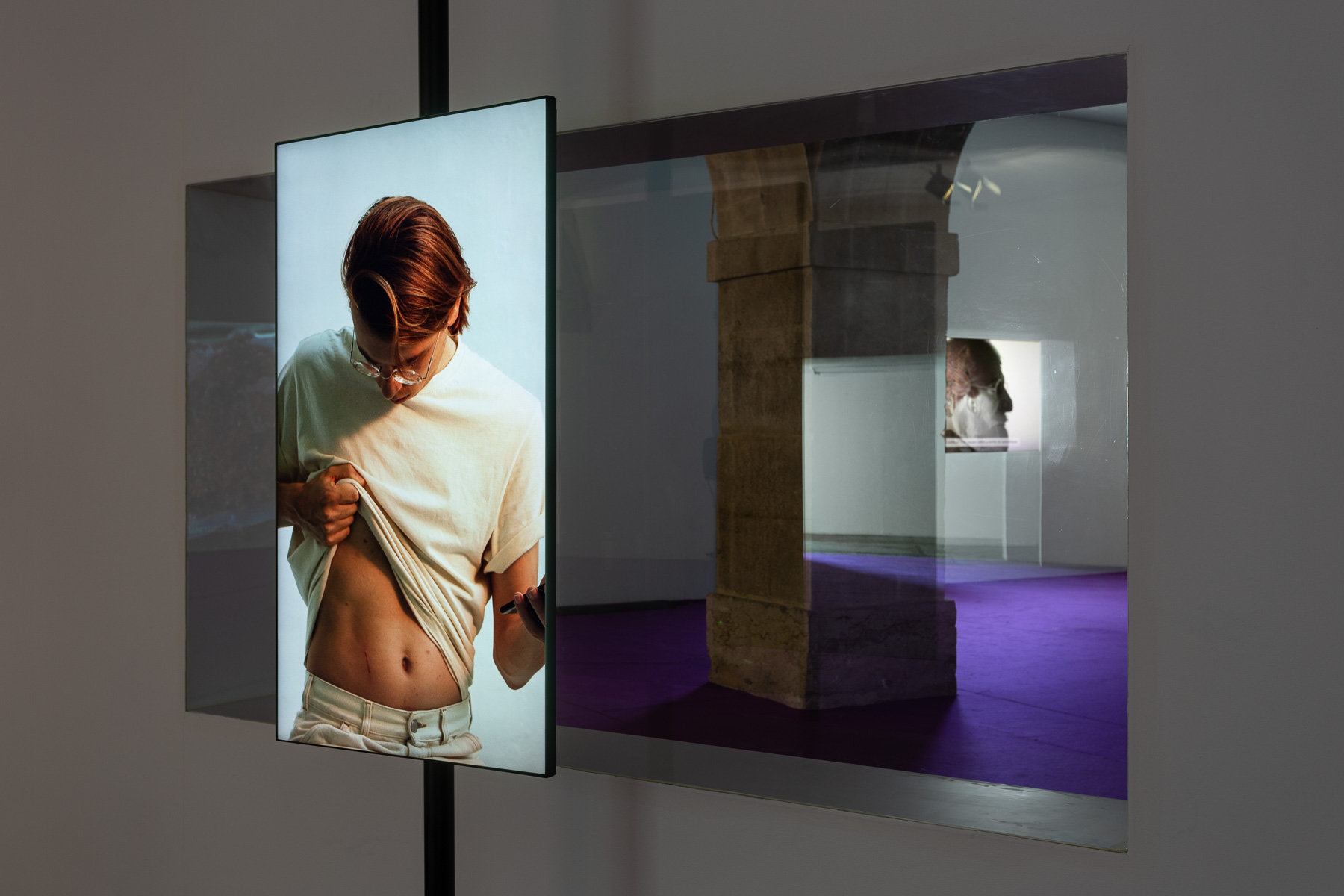

At Lisbon’s Galeria do Torreão Nascente da Cordoaria Nacional, Pedro Neves Marques brings together a group of five works—two short films, a voice-led installation, a digital animation and a suite of photos—made between 2019-21. Installed on top of a Papal-purple carpet, and bathed in the hypnagogic soundtracks of the artist’s collaborator HAUT, these works feel like limbs extending from a central conceptual body, speculating, like exploratory tentacles, upon questions of reproduction, replication and representation—of bodies, ideas, roles and identities—through a balance of empathy, critique and affect.

As a line in Neves Marques’ forthcoming short film puts it—another spawn from this corpus of works—spoken by the character Vincent, who is played by the artist themself: “These things between body and mind aren’t that linear.”

In a conversation conducted by video call, on 3 September 2021, Pedro Neves Marques reflected with Justin Jaeckle upon their exhibition Medieval Bodies.

Justin Jaeckle (JJ): For those who might not have been able to visit the exhibition itself, it would be interesting to drill down on what the show is composed of, to hear you reflect on it now.

Pedro Neves Marques : Being very practical, it started with the installation Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, which came out of the Present Future Art Prize that I was awarded in Italy in 2018, and which I then exhibited at Castello di Rivoli. Sonically, I really wanted it to be something between a short story and a podcast, in the way that it’s interrupted by fragments other than the main narrative. That’s how I worked with the music producer HAUT, a regular collaborator of mine. I also wanted to include my poetry, in the video element, where you see me reading these poems, but you can’t hear what I’m saying. That was the first work.

Later, I felt there was so much in there that I kept going with it, and I ended up doing the series of photo-poems [Autofiction Poems (2020)]. It’s the same image as in the first installation, with me holding a phone with on-screen poems in my hand, but in the photos you have the time to read them. The poems speak to gender, performativity, reproduction, and autofiction – the violence of a writer, let’s say, when they start fictionalising. When the Liverpool Biennial, curated by Manuela Moscoso, commissioned me to do a new piece I started to work simultaneously on a new short film — for cinemas — and also two artist films for the biennial: The Ovary (2021), which ties in directly with Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, but takes the form of a sort of music video; and Meat is Not Murder (2021), which is kind of an anecdote, a micro-story, about a vegan who is challenged to eat lab-grown meat.

I wasn’t thinking of adding any other work to the exhibition in Lisbon, but talking with Luís Silva, the curator, I had this idea about psychoanalysis. I wasn’t really sure about it; I asked myself ‘Do I really wanna go there?’. And Luis was like, ‘I think you’re already there! So just do the work!’. And so I did it: a five-minute digital animation titled The Early Death of Sigmund Freud (2021), where nanobots are sent back in time, Terminator-style, to kill Freud before he invents psychoanalysis.

JJ: I wanted to start by unpacking the exhibition’s title — Medieval Bodies — and that of the sound and video installation at its centre Becoming Male in the Middle Ages (2019). These titles are hugely evocative, and given that language is so central to your practice as an artist, their resonance feels extra significant.

PNM: Becoming Male in the Middle Ages is actually the title of a book I found some years ago; an academic book on queer studies and the making of masculinity in medieval times. I kept that imaginary of the medieval production of gender with me and began to think about it as an epoch when certain terms start to become more fuzzy and fluid. That’s how I’m thinking of medieval bodies, medieval times, and that imagery – in the artworks and in the show. Medieval time more in the sense of a period when stereotyped roles are under dispute, become quite messy, and the way technologies and the sciences are part of that shift. Hopefully that’s something you find in the show. You have all these categories of gender and performative roles, and then technology allowing those roles to become increasingly confused. So medieval time is not a literal reference to the medieval period, but more to a feeling of the ground shifting underneath you, let’s say.

JJ: I’m interested as well in this idea of the ‘middle’ — these other implicit middles that are maybe signposted by the title, and that are definitely dealt with in the exhibition’s content. The installation Becoming Male in the Middle Ages tells the story of four friends: a heterosexual couple struggling with fertility issues and having a baby (which the woman doesn’t want); and a gay male couple attempting to have a biological child through an experimental technique of implanting ovaries in a cis male body. In the work’s final chapter, Marwa, the main protagonist, sits on ‘the lawn of the excluded middle’. Marwa’s in her 30s, and there’s a suggestion of the 30s as a form of middle age, maybe, representing a certain fork in the road – especially for cis-gendered women in terms of their ‘biological clocks’. There feels to be an extended conversation about these and other middles.

PNM: All these works and films actually came from very informal conversations I was having with friends and people around me, many of them in a kind of ‘middle age’. Like you were saying: cis-gendered friends of mine, in their late-30s or early 40s, having to deal with the pressure of having babies or not. How that impacts their relationships, and all of that violence and frustration. But on the other hand, also gay friends processing similar desires – of adoption, or ‘we really want a baby’. There’s a certain violence in those conversations, in those choices. I think in these artworks, especially in Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, I was trying to find a balance between understanding and empathy for those issues, whilst at the same time being very critical of them – in terms of the performances that they reproduce.

JJ: I’m interested in what the middle represents to you. The exhibition enacts this delicate balance of empathy and critique towards certain ideas of hetero- and homo-normativity, which we could assume to be at the centre of the show. And there’s this debate, perhaps, about whether the centre, or the middle, is positive or negative; a place of collectivity or exclusion.

PNM: Between empathy and critique — I like that. I think that’s exactly the balance I was searching for. And I think affect, and emotion, at the end of the day is a way to kind of navigate those extremes. Of course politically I’m also thinking about legacies, for example being the inheritor and beneficiary of previous emancipatory LGBTQI+ struggles — and homonormativity being at odds with that.

In a way I can understand the desire to be ‘in the middle’ politically, but you have to wonder about what’s left out in the violence that is implied in that position. In this case, I think the relationships I establish in that first installation, Becoming Male…, are something that I see a lot around me; a kind of blindness, ignorance even, of cis men towards women’s mental and bodily health, for example. I’d also like to say that, in more practical terms, Lawn of Excluded Middle is a collection of poems by the North American poet Rosemarie Waldrop. For Waldrop, the lawn of the excluded middle is a space of feminism in relation to the body, and the violence of not having a space — performing a space but then not having a space. I love her work and she was very important to me early on.

JJ: One of the most powerful things about the exhibition is the way it collects these discreet works made between 2019-2021, which had previously not been shown together, and presents us with them as a kind of constellation. To some extent it feels like a world-building exercise. The Ovary and Meat is Not Murder end up filling in certain back-stories, maybe, to Becoming Male in the Middle Ages. And then I’m really interested in this new Freud work because it feels like a piece of acupuncture, that very definitively affects or contaminates how we read these other works. I would like to ask you how you view these works together. Are they like a family for you, siblings to each other? How do they relate to an evolving process?

PNM: I think it’s two things. One is what you mention, there’s this world-building quality that I’ve become really fond of. The other is about how I’ve come to understand the space of contemporary art and exhibiting in a gallery, compared to showing a film in a cinema.

World-building is a sci-fi and fantasy term, and I am super devoted to those genres. So I mean world-building in the sense of setting the terms and the rules to talk about a subject matter. I’ve learned to stick with the stories that I imagine; to not let go very quickly — which could be easy, you know, with demands like ‘what’s next?’. But no, let me stay a bit longer, out of respect for the subject. I think that came to me through a previous work of mine, Exterminator Seed (2017) — my first true fiction film, shot in Brazil. That film created such a community of sorts between the team, we just kept our dialogue going. That led me to make other films in that series, a wall-text installation, the actress Zahy Guajajara wrote a sound piece, there’s been an Anime-like animation in collaboration with illustrator Hetamoé, and we’ve just shot a new short film together in Lisbon this summer — it’s a matter of dedication and caring to the prismatic quality of an idea. I think that really shifted the way I was thinking about commitment to both the people involved and the stories that I imagine, especially when they are sometimes so weird. So I made Becoming Male… and felt it deserved more attention — to just kind of let it spawn.

And then there’s the part about cinema. When I started doing cinema about five years ago it was really helpful for me to look back at my relationship with contemporary art. Cinema makes me ask myself, ‘OK, what do I really like about exhibiting in a gallery or a museum?’ I see contemporary art as very discursive, even cerebral to a point. I appreciate that. To me it is, like you’re saying, acupuncture; creating relationships, installing things next to each other, seeing what happens in between the lines. While cinema is for me pure storytelling; I just want you to sit down and see a story, no matter how political it is. Those have become my rules, in a way.

JJ: The artworks presented within the exhibition in Lisbon are in part composite elements for a forthcoming short film for the cinema — also titled Becoming Male in the Middle Ages — which will premiere soon. And this discussion about cinema opens a couple of paths for me. One of which is in connection to these ideas about a project having multiple limbs; so the question of when a project is finished for you, or if it is ever finished? I’m intrigued by the role the short films occupy within that kind of thinking. About whether these films, in the end, act as a kind of punctuation mark for you within a project, a time capsule of its ideas?

PNM: On a practical level cinema and contemporary art have very different temporalities and timelines. And different cycles of production and funding as well. I take quite some time between shooting a film and going into editing. I need to take some time off from the images and the story. And I feel working with the images and the stories that I choose for a gallery is a way for me to get acquainted with what I’ve done. It helps me understand the film that will later go to cinemas. I start by doing small batches of editing, using the images in a different way than I initially thought. That really helps me get to how I’m going to edit the final film.

JJ: I was discussing being interested in how the works presented in this exhibition have a certain harmony together, this world-building character. But there’s also something else happening within your work, and certainly within this show, which is a kind of choreography of dissonance, we could say. That feels especially true of the installation Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, in which you have a soundtrack that’s 35 minutes and a mute eight-minute looped video at its centre. Out of sync, basically, right? So you have that conflict to start with. Then we have the fact that your voice, which may register to some as male, is reading the narrative of the story, whose protagonist and first-person narrator is a cis-gendered female. So there’s another kind of dissonance that goes on there. And then we also have this division between trying to read your very intimate poems off the screen — which is what we’re presented with visually — whilst listening to the parallel prose and facts delivered by the voiceover. So it would be interesting to speak a little about the choreography of attention and conflict that happens within this.

PNM: Dissonance and a certain disrespect for how certain things should work — what certain people should be, or what should or should not connect with what — is very dear to me. Sometimes that’s translated into the editing or the relationship between sound and image, other times its more narrative, discursive, and political. I’m interested in a certain violence, even, in that exercise, of trying to kind of rupture — sometimes consciously, sometimes very much to my own surprise — with expectations about specific roles. I like to push for a little bit of a resistance to those attributed roles. Like an android that’s played by an Indigenous woman, in the YWY series of films and artworks that I just mentioned — what kind of tension about possible futures and ontological worlds does that create? Or an analogy between controlling the reproduction of a disease-carrying mosquito and the reality of queer lives, as in my film The Bite (2020)? Or here, a cis-gendered man trying to gestate.

JJ: In these elements of dissonance, these tensions, there’s a certain mirroring that’s happening between form and subject. Because the content that you’re engaging with is also ‘slippery’

PNM: Yes, and I think the Autofiction Poems on show at Torreão Nascente, for example, are important because they are about the fragility and exposure you need to allow yourself in order to create those tensions. Fragility is a difficult place to work from, because you need to be really careful about this balancing act between creativity and honesty, political commitments and necessary yet perhaps counter-intuitive speculative exercises. To me that rings particularly strongly in this group of artworks, because they are much more autobiographical than anything I’ve ever done. I’m in my work for the first time; in using my image and voice but also in the fiction. This demands a specific kind of exposure of yourself.

In Autofiction Poems I really allow myself to be there, despite the confusion between my story — my biographical story — and the stuff that friends tell me that I then write in my own name, or vice versa. Besides that, these poems are very concretely about gender, sexuality, expectations, all of this intimacy. And then, if we are going to talk about this forthcoming film for cinema, also titled Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, it was both unexpected and extremely obvious that I ended up playing the gay guy who has an ovarian implant. That wasn’t initially the plan. I was casting someone for that role but we couldn’t find anyone and I was getting really frustrated. And then it was Isabel Costa, the actress whom I had already cast, who told me, ‘Why don’t you do it? Why isn’t this man you?’. And I was like, of course it’s me! And it was really fun, because since entering into a trans non-binary process I’ve ceased to identify as a man. It gave me an almost anthropological perspective on myself and on a masculinity that was never really mine to begin with.

JJ: The poems also frame one of the other tensions within the show: the nature of sex itself. In them there’s sex as liberation, or sex as care as you’ve phrased it in the title of your previous collection of poetry [Sex as Care and Other Viral Poems (2020)]. But then we have a narrative in your ‘medieval’ stories that’s dealing with sex explicitly as a reproductive act. And I find that tension plays out all over the exhibition. Your Autofiction Poems again take on reproduction, in a different way, in terms of the same image being repeated across 13 photographs, with different texts. And the nature of reproduction is there in Meat is Not Murder, via ‘artificial’ lab grown meat.

PNM: Sexuality to me is where we sublimate a lot of social violence. And it’s such an amazing place to write from. I think in these works the relation between sex and reproduction becomes quite central, because again, what does reproduction do to sex? How does reproduction, once it shows up in a relationship for example, contain or transform sex?

In Becoming Male in the Middle Ages sexuality is attached to reproduction. You have reproduction that supposedly shouldn’t belong to a particular body — the cis-gendered man — but is being able to exist due to technology. At the same time you have a woman who is being pressured by her boyfriend to have the baby that she never wanted. I imagine this heterosexual couple to be really sexually liberated, but then completely ruined by the introduction of reproduction. And then the irony, if it’s irony, is that at the end of the story she leaves her boyfriend, who was trying to have a baby with her, to be the surrogate mother for these two gay guys. And it’s such a question mark to me: why would she do that?

There’s this sentence in The Ovary, which came to me later: “Who’s to judge which is the biggest love?” The love of someone who denies a partner from having a baby, or the love of someone who never wanted a baby but who nonetheless cedes to their partner’s desire out of care? Violence is all over the place in these relationships. Violence in relationships between people who really care for each other. That was something that was definitely also in my film and homonymous installation The Bite (2019-2020). In that case it was in the context of a queer community, and it asked how do we care for each other despite our differences, or within the violence of our differences? I think here it’s similar, but in a more normative context. All of these works are very much about normativity.

JJ: There’s a lot within this conversation about trying to go beyond binaries, both personally and also as something germane to the works themselves. I have this constant curiosity about whether gender parity is even possible until reproduction is removed from sex.

PNM: I guess the ideal would be exowombs, wombs outside of any body. To decouple gestation and reproduction from any gender. Maybe equality would come from that, maybe not, but it’s a question that was posed especially in the ‘60s with Shulamith Firestone and other feminist authors, and I think it’s coming up again because of technological advances. It takes time for an image to fall from science fiction into reality. Hopefully in my works gender is always fluid, and that’s how I like to see that category play out — also because of my own life, my own transness.

JJ: What’s interesting as well is the combination of that exploration with your critical position, in regards to the ways that heteronormativity can reproduce itself — or how progressive agendas can accidentally lead to conservative outcomes. The way, perhaps, that femme/butch archetypes, even through subversion, can reinforce certain notions of what masculinity and femininity are. Given your heavy engagement in ecology, I was thinking back to a piece I recently read proposing the possible/probable absorption of climate politics and catastrophe into fascist agendas — how we should actually be very scared of the end of climate denial. This was referred to as avocado politics — green on the outside, brown(shirt) on the inside — in comparison to watermelon politics — ‘red’ socialist agendas hiding behind a ‘green’ skin. And I feel there’s a parallel here to something that weaves throughout the works within this show; an awareness of the unknown consequences of certain thoughts and actions – or rather how progressive intentions can easily lead elsewhere.

PNM: To be very honest, I’ve been struggling with something similar. That is, people associating reproduction and gestation with a very second wave kind of feminist position — women’s blood and the earth, the sacredness of women’s biology... This almost telluric view of womanhood, associating cis-women’s gestation with nature, and a very colonial-framed image of nature at that. And if you come from a trans perspective, or a fluid non-binary perspective – or even from a more ecological perspective — that’s really problematic and violent. Queerness has changed ecology, and as such it should also change past feminist perspectives. It’s again a struggle between empathy and critique. Of course I understand what that kind of feminist discourse means, especially historically, but how can someone like me coexist with it nowadays, knowing that it risks being exclusionary, as with TERFS? I think this series of works puncture that a little bit. Not explicitly, because that was not my conscious intention, but the works do kind of touch on that.

JJ: Another long-standing investment of yours is in critical thinking about capitalism and where it emerges. And I think it’s interesting that within this show the question of reproduction and/as ownership becomes quite present. Two of your characters very much ‘want’ to ‘have’ a child, with a definite compulsion towards it as an object, whilst both their partners are more ambiguous, less into this question of ownership and biological self-replication. So these questions of self and possession, the body and accumulation, I find it very interesting how that rolls out within this conversation on reproduction, of having a child ‘of one’s own’. And I wondered to what extent you thought about these bodies and these subjects within that frame, which in turn leads us to questions of identity.

PNM: Having a baby becomes such a part of some people’s identity, and it’s sometimes curious — does that person want the baby, or do they want the structure the baby offers? I think that’s an interesting question: what is really the desire behind reproduction; whom does it serve? I’m very much interested in the female character, Marwa, in all these works, that aspect of refusal that she embodies. And at the same time how caring she is, for the others. I feel she’s always allowing this violence, always giving a little bit of herself. She’s always like: My boyfriend, OK, you want a baby, OK, let’s have a baby… My friends, OK, you’re being normative etc., but I’m still with you, I’m still going to go through the emotional labour of all these failures. And then finally, there you go: you want a surrogate mother? I’ll do it. All of this until that last moment when she takes a stand. But then the decision that she makes is not the one that I would expect. She decides: OK, I’m going to have this baby who isn’t mine, but on my own terms. She’s not having her baby, the baby her partner wanted to have with her; she’s having a baby on her own terms. I think in the end she corners the guys.

JJ: It would be interesting to go into this narrative more — about a gay couple seeking a baby through an ovarian transplant into a cis-male — and how it speaks to your approach to pop or alt-culture. Can we talk a little about Mpreg, the ‘male pregnancy’ genre of online fan-fiction you’re engaging with in Becoming Male… and The Ovary?

PNM: I was at a dinner once and one of the guests was making a living writing Mpreg e-books to be sold on Amazon. It was just so intriguing. So it just started from randomly discovering Mpreg — this male pregnancy subgenre of online aesthetics and literature. I ended up reading a bunch of these stories; boys-love Mpreg, sci-fi Mpreg, werewolf Mpreg, all sorts, very normative ones as well. At some point I found myself going from bookshop to bookshop in Tokyo searching for Mpreg stories — the trend started in Japan. My fascination, I now understand, was about normativity. That’s something that’s so interesting with Mpreg; being a very gay male oriented imaginary, but having the normativity of reproduction and of performative roles at its core — the manly gay is always the dad, and the more feminine one is the one who gestates. It’s highly problematic! In the end, my critique, let’s say, of Mpreg was writing an Mpreg story myself. I think that was the best homage to the genre. I have a deep love for b-genres, in cinema, in literature. I find that they tell us a lot. Of course they don’t have the best cinematography, they don’t have the best literary quality, but that’s not the whole point is it? I’m fond of b-movies, Dario Argento, John Carpenter, or the thin line of David Cronenberg’s career.

JJ: To reflect more on pop and genre: you earlier described The Ovary as a music video, in essence perhaps because it’s centred around a cover of Let Me Love You Like a Woman, by Lana Del Rey, as performed by your collaborator HAUT. I’m intrigued to what extent Lana’s song was a catalyst for that work?

PNM: Very much.

JJ: Because the song comes out in 2020, between Becoming Male in the Middle Ages (2019) and your two films for the 2021 Liverpool Biennial.

PNM: I’m a huge fan of Lana Del Rey, I can say that unapologetically! And when HAUT initially asked me for directions for what they should compose for the Becoming Male… installation, I told them, well, I’m thinking a lot about pop lately, and I think a lot about Lana Del Rey as the feeling of pop. Not Lana Del Rey literally, but the feeling. I’m also not interested in pop necessarily, but rather this kind of emotional warmth that pop offers – which maybe in the exhibition we understand as harmonious, as soothing, maybe that’s the pop that I’m talking about. I discussed this with HAUT, and they made this beautiful and complex 35-minute composition for Becoming Male…, evoking both club music and pop. But then later on, when I was starting to make the films for the Liverpool Biennial, HAUT literally sent me a Lana Del Rey cover! Which I didn’t ask for!

JJ: As a personal present, or with an anticipation that that cover would be the backbone of your film?

PNM: I had just given Lana Del Rey as a sensorial reference, but then HAUT actually did a cover of Let Me Love You Like a Woman – which I was blown away by. It was so beautiful. To me it’s such an ambiguous song, you know? It’s about gender and performativity… It’s very trans. Superimposing that song on my images hopefully gave it another direction and reading; and it just created a sort of music video – which is the embodiment of pop, right? I couldn’t be happier.

JJ: It was such a beautiful surprise within the exhibition space as well. There’s a kind of spectral quality to the HAUT cover, and the original song only slowly reveals itself until you finally realise it connects back to Lana, to Let Me Love You Like a Woman. And the song’s content then offers another further complication in terms of the sex and gender plays that we have happening within the exhibition. I share your love of Lana, in part because it always feels like there’s this aspect of her being a pop star in drag, of her wearing the drag of a pop star.

PNM: Totally!

JJ: She’s acting-acting-the-pop-star, and finds her authenticity through a transparent inauthenticity.

PNM: Exactly, I think that’s what’s so beautiful about Lana Del Rey. Everything is artificial about her, but within the artificiality there’s such honesty. And such intimacy. For me that’s very much the opposite of Lady Gaga perhaps – which is pure artificiality. But Lana, she kind of breaks down the contradiction between artificiality and intimacy. Again, those unexpected contradictions that I was mentioning earlier.

JJ: Absolutely. And there’s a unity of form and content with Lana, which I don’t feel in Gaga. Gaga’s basically like a lounge bar singer-songwriter but is styled like Björk, right? I’ve always wished there was more adventure within Gaga’s production and songwriting itself. In Lana there is this total unity. And it’s interesting as well, when you were describing the character of Marwa in your work, and this idea of refusal, I began to think about Lana, who I knew I wanted to talk about later – because Lana’s position is one of refusal, right?

PNM: Absolutely.

JJ: Lana’s gender construction is also kind of interesting; we have these faded pastels, baby-like vulnerability, but she’s wearing this kind of cloak of ‘fuck you’, this cloak of disinterest, this cloak of refusal.

PNM: And being very autonomous and independent in that refusal. I think there’s great strength in vulnerability. I think both Lana and the character of Marwa speak to that. It was actually around the image of the character of Marwa at the gynaecologist that I edited The Ovary. I had all these images, most of which, not all, are part of the forthcoming film. I had these images and I didn’t really know how to work them in a less narrative way. And when I started to really look at that image of the character in the gynaecologist – the look in her eyes – the acting was so strong to me. And I was looking at the images already listening to HAUT’s Lana Del Rey cover. So the song came first, and it helped me understand what I wanted to do with the images. It was, from the beginning, Lana Del Rey.

JJ: I’d like to come back to this conversation about prose and poetry. Not just in terms of the written or spoken word, but also as affect. When we’re talking about the move between cinema and images or objects, when we talk of things starting from the written word — Becoming Male… beginning as a literal story, and then becoming something else — I’m interested in this interplay that’s in the work. As someone who has come to writing poetry more recently – after a heavy, heavy engagement with prose, the essay and theory — I’d like to know if you correlate that somehow to the different tones that are being explored in this show, these competing means of registering the world.

PNM: I’ve been invested in critical thinking; that’s part of my background in terms of formative schooling. Prose has also been more central to me, having published short stories. But there was a moment in my personal life, and also in the world falling into ever smaller pieces, where poetry became basically the only voice that I could speak in. It came as a surprise to me, I confess. When I was still living in New York I was hanging out with or listening to poets, people around the Poetry Project for example. I never dared to become a poet, because they were so good at it. But that context really gave me a lot, and poetry became, in a very normal way, the only form I could really speak out in. And from there the poems started to enter my art practice.

I think the Autofiction Poems are very obvious and explicit about how I perceive poetry, which for me is the perfect place for a balance between fiction and speculation. A place where you always read me, without that voice necessarily being me. There’s this confusion, this space of fragility. That’s poetry for me. That space of fragility. I don’t see my poetry as being determinative, as imposing itself or being very categorical. It’s much more of a space of exposure. At some point I realised this is what I need.

JJ: That circles me back, in counterpoint, to the idea of art as a weapon. We’ve been talking about fragility, but in the exhibition itself at Galeria do Torreão Nascente we have a digital animation speculating on the death of Sigmund Freud – by nanobots, you kill him off; you then also have a certain war on heteronormativity; a certain battle of the sexes. We’ve been talking about the deeply personal and the fragile, but there’s also a violence that’s both dealt with as a subject in the works, and that is also maybe of the works themselves. I’m interested in how you view the agency of your works, as artworks, in relation to your own personal politics.

PNM: There’s never a clear answer to these questions around art and politics, right? It’s impossible to arrive at a conclusion. But perhaps one thing that I see, in the way I work, one thing art can do is at least create ruptures with pre-determined categories and expectations. Kind of pulling the rug from all of these things that are taken for granted, for better and worse. So I speak both for the left of the political spectrum, and the right of the political spectrum. I mean the power of speculating on how things can be, differently: that resonates. I think that’s political in itself, and it has an impact. It may not be a direct impact, but if you don’t believe that art does create small revolutions of sorts, then why the hell do you make art? My artworks won’t stop monocultural transgenics, they won’t stop transphobia, or homophobia. That’s too much of a burden. That’s your own civic duty. But they can participate in those conversations, and hopefully participate under unruly terms. And I feel that’s already a lot.

Justin Jaeckle is a curator, writer and editor working across contemporary culture, art and the moving image. He is a programmer, since 2016, for Doclisboa International Film Festival. He has previously curated programmes for and in partnership with numerous cultural institutions, including Tate, Design Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum, Auto Italia and Cinemateca Portuguesa. Since 2008 he has curated the bi-monthly Architecture Foundation/Barbican series Architecture on Film. He has written for titles including Art Review, Frieze, Octopus Notes and Wallpaper*. He studied Fine Art at Central St Martins.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro.

Pedro Neves Marques: Medieval Bodies. Exhibition views Torreão Nascente da Cordoaria Nacional. Galerias Municipais/Egeac. Photos: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of Galerias Municipais/Egeac. Autofiction Poems, 2020. Courtesy Galleria Umberto Di Marino.