Interview with Coco Fusco

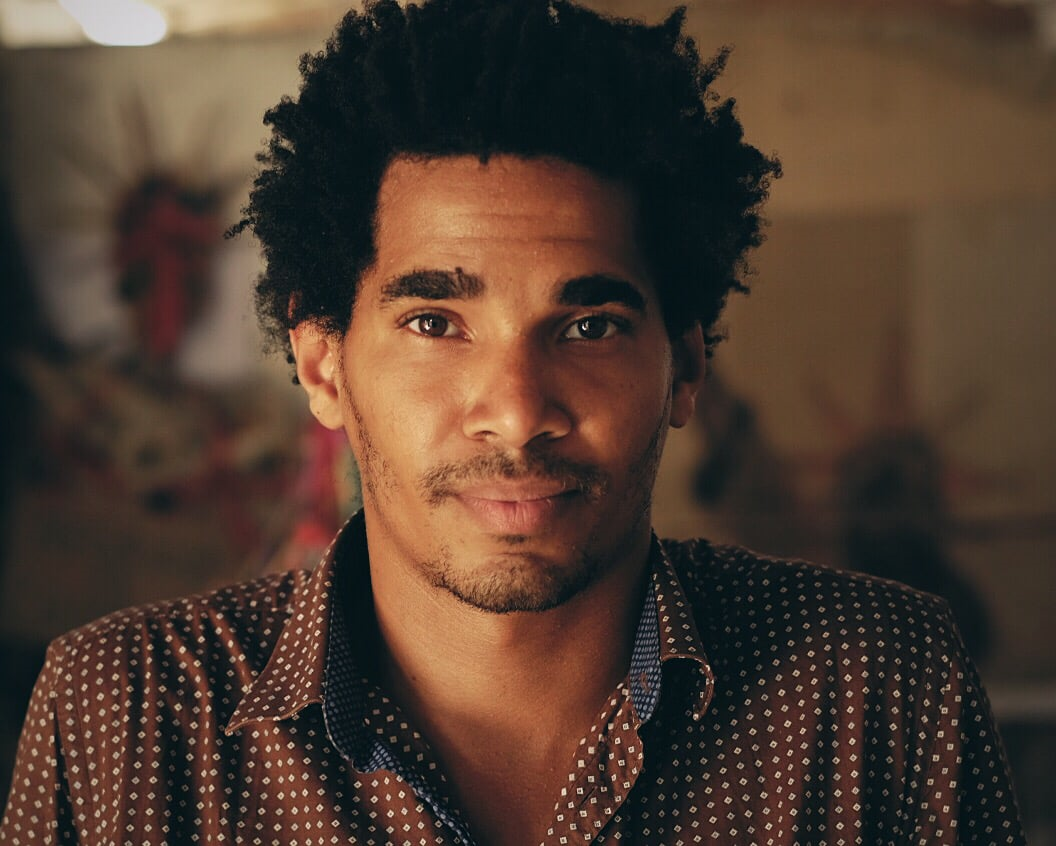

Photo: Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, prisoner of conscience and artist.

Coco Fusco is a Cuban-American artist and writer based in New York. Her interdisciplinary artistic and theoretical-critical production, which incudes performance, video, curating and writing, addresses such issues and topics as post-colonialism and race, globalization and labor. For the past three decades she has conducted research and produced written and filmic work about post-revolutionary Cuba. In her recent videos and book about Cuban performance art she offers critical readings of the mechanisms of state power and their impact on Cuban artists. She details how artist and intellectuals have been perceived and treated as politically suspect at different stages of the Cuban revolution, despite the fact culture has consistently been a means for the Cuban government to project an image of itself globally as a benevolent power. In the early years of the revolution, many Cuban intellectuals were derided as bourgeois holdovers of a pre-revolutionary eras. Gay intellectuals were also singled out for intense persecution. Because Coco Fusco has supposed activist efforts by Cuban artists and intellectuals that have claimed the right to develop independent culture on the island and have contested new legislation aimed at criminalizing such activity, was refused entry to Cuba in 2018 and 2019. But Fusco argues:

"Freedom is conditional in several contexts and many governments limit the different ways in which we can protest".

This should concern us all.

Eduarda Neves (EN): The pandemic resulting from COVID19, at least in Europe, had only 48 hours of dissemination and a number of intellectuals already had all their usual theoretical apparatus to apply to the coronavirus. Some of these readings would also apply to the church, to sex, to the world at large; sometimes, only the object changes. Do you think that even intellectuals are subjugated to the rapid mode of production raised by capital? How does this crisis that we are going through influences your working conditions and even your mode of production?

Coco Fusco (CF): Of course public intellectuals are affected by the same accelerated demands for production that the rest of the laboring world is. The news cycle now operates at a frantic pace by comparison to the way it was in my childhood, when TV news broadcast only in the morning and evening and newspapers printed once or twice a day. Now news websites on constantly updated, and outlets compete viciously to be the first to break a story. That means that demand for news content has exploded, as is the demand for commentary that provides a framework for managing the every expanding information flow. As for how this affects me, well, not really that much since the kind of journalism I occasionally engage in is not so news related or news dependent. I also don’t think that art is the most effective quick response to world events. Art can open us up to deeper levels of perception and understanding achieving that takes time.

EN: In 2020, the existence of mass graves in the U.S.A., in which the dead are being placed, can inform us more about the world we live in than many theories about COVID19 and capital. When the body goes out of existence, is it our collective face that emerges?

CF: I don’t know if I really understand your question here. The problem of what to do with so many dead people is not exclusively American. We first starting hearing about bodies piling up in Italy, then Spain. I imagine this happened in China as well but the news of the epidemic there was more controlled. In the US the only city that has this problem at present is New York. We reached a peak of 800 deaths per day about a week ago and now the number of deaths daily is going down. The industries tied to management of the dead — morgues, funeral parlors, crematoriums, cemeteries, etc. — are not equipped to handle that number of dead bodies at once. In New York right now there are not enough cemetery plots available, and, there are many dead people with families that cannot afford to bury them. Hence, we have the revival of the use of mass graves. Hart’s Island in the Bronx has had a potter’s field — a mass grave for unclaimed, indigent and unknown people — since the mid-19th century. In short, this is not the first time that the number of unclaimed dead becomes a problem in the US and it will not be the last.

EN: Coco, it is in performance and video that you seem to find your singular space of overcoming [superação] that, by the way, in Portuguese, rhymes with transgression [transgressão]. Are these tools the ones that best operate within the scope of your artistic program, a kind of critical restitution of the real, thus allowing the denunciation of the ideological apparatus of the State and the multiple ways through which power is exercised?

CF: I don’t think performance and vídeo are especially suited to social critique, more than other art forms. Many other artists engage in social criticism through painting, photography and sculpture. It may be easier to tell stories in time-based media since you can elaborate and show developments over time, but visual art that is static can also offer powerful metaphors. Right before the pandemic started, I saw the Gerhard Richter exhibition at the Met Breuer. The show includes his suite of paintings entitled Birkenau (2014) that are based on the only known photographs taken by prisoners inside the Nazi concentration camp. The paintings are not literal depictions of the content of the photos, but they are ruminations on those images and the problematics of historical memory and trauma.

EN: I´m not claiming that performance or video are more suited to social criticism. I’m only asking if, for you, these are the means that best fit your artistic practice.

CF: I don’t accord them a special status with regard to the real.

EN: However, although performance and video occupy a central place in your work, can we say that the photographic image also functions as a critical medium and document in some of your projects?

CF: I have worked with photography in a number of ways. I will give on key example. In 2003, an exhibition I worked on as co-curator for four years, entitled Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self, opened at the International Center for Photography in New York and then traveled for a year. It was a comprehensive study of the history of racial representation in American photography. My curatorial premise was that race is a pseudo-scientific discourse in which photography has play a key evidentiary function, constructing and sustaining the idea that race is real and that it marks bodies. Even those artists and anthropologists and social scientists that considered themselves anti-racist relied on photography to represent racial difference.

EN: When you participated in the Porto Future Forum, in 2019, you presented a fiercely critical communication concerning the Cuban government. Do you still think that “the Habana Biennial, (is) the real showcase, designed to seduce foreigners and convince them that Cuba is a paradise for artists”?

CF: I would not characterize my presentation as fiercely critical. I strive to be analytical but unfortunately, many Europeans refuse to engage in any sort of rational analysis of Cuba’s political system. I think that refusal is a symptom of the unchecked allegiance that most Europeans maintain to the idea that the Cuban revolution is perfect and untouchable or that to criticize the Cuban government is an endorsement of capitalism. I can also be critical of the American political system while recognizing its inequities and the histories of oppression that are part of what America is. All art biennials in peripheral countries represent major sources of tourist income. All art biennials are occasions for professional networking, whether they are in Venice or Shanghai or Sao Paulo or elsewhere. And art biennials often serve political and ideological purposes. The Sharjah Biennale has been subject to a great deal of scrutiny because of its censorship of artists and also because it is perceived by some to function as false front of openness in a strictly regulated social environment. The Venice Biennale was founded in 1895 to showcase “the most noble activities of the modern spirit without distinction of country.” In other words, it was intended to present a view of the first world as the locus and engine of modernity. It was not until decades after its founding that non-Western nations gained national pavilions and it is impossible not to read that as politically determined. During the 1930s the Venice Biennale was controlled by Mussolini’s Fascist government and many scholars have studied how the event became a vehicle for Fascist ideology. So why not subject the Havana Bienal to the same kind of analysis? As for its effect on foreigners, the event has achieved the goal of convincing visitors that Cuba is a paradise for artists.

EN: In an interview with Carlos Aguillera, you said that: “Nowadays, almost all artists have become businessmen and they know that the State allows them to become rich if their work does not touch politics and that, in addition, the international market prefers an art from the ‘Global South’ that mixes the conceptual with the anthropological and leaves out politics.”

Several Cuban artists criticize the regime both inside and outside Cuba. Who can be interested in buying Cuban, politicized art, that denounces the pressures of the regime? Is the “Global South” on its way to becoming a financial brand?

CF: Many international museums and collectors by Cuban art that has a political edge. Tania Bruguera’s work is in MoMA’s collection for example. Ella Fontanels Cisneros has purchased works by Hamlet Lavastida. Jorge Perez, the patron of the Perez Museum in Miami, owns a large collection of contemporary Cuban art that includes works that are critical of the government. I don’t understand why there would be any doubt as to whether work critical of the Cuban government would not be sellable. As for whether the Global South is a brand, I cannot say. I think the term is too general for branding. What has happened since the 1990s is that collecting of contemporary art has become a global endeavor on an unprecedented scale. That means that there are significant arts patrons based in countries such as India, Brazil, Mexico, the UAE, China and Russia as well as in the US and Europe. They do not only collect work from their regions but they don’t exclude those works either and many make important donations to European and American museums with the understanding that this will ensure that curatorial practices in those museums will change. Some of these patrons, such as Patricia Cisneros, fund curatorial positions focusing on their regions. What I am explaining here is that institutional practices in the developed world are changing because international finance has changed it.

EN: Despite the fact that, in recent years, a series of contributions appeared — from reports, essays, exhibitions — that reflect upon the cynical relations between intellectuals and Cuban power, can we think that there, like here, cynicism is global and multicultural and does not know gender? Is it, let’s say, intersectional, to speak according to a dated academic language but a quite trendy one in art and in the so-called cultivated culture? In other words, in Cuba, as, after all, in any other country, the one who wants power must be willing to serve it?

CF: I am really not sure if I understand your question. Are you saying that everyone in the artworld has a cynical relation to power? Perhaps. I am not sure that such generalizations are useful. It is more useful for me to analyze the mechanisms and dynamics of power relations in different contexts. How artists contend with totalitarianism, how some may or may not try to court favor with the state, these things may be similar to how artists in capitalist countries cooperate with conservative art collectors or curators. But if I focus on what is the same, I cannot understand what is different and specific to operating in an authoritarian society where choices are far more limited, where State power is all encompassing, and where information is tightly controlled.

EN: You said that: “There will always be some conservatives who will refuse the use of non-traditional materials. They just want to see canvases painted with oil and stone or metal sculptures. That attitude is not only manifested in Cuba, it exists everywhere. Nevertheless, there are artists in the island who work with blood, excrement, saliva, etc., and they are accepted because their way of using these materials does not imply criticism of the government. In the case of Ángel Delgado: he decided to shit over the Communist Party of Cuba newspaper and was not invited to the exhibition that he was supposed to take part - there was the problem.“

Is this guarantee of freedom in artistic practice that you find in the USA, a country that, as we know, also censors films, books and exhibitions, through various forms of moral pressure, be they social, religious or political?

CF: I never said that I find artistic freedom in the USA. I would not say that artistic freedom is guaranteed in the United States. There are famous cases of censored literary works throughout the 20th century. A number of artists have been arrested on obscenity charges because of their use of nudity, the eroticism in certain works, and homoerotic content. Artists that work in public space have been arrested for public disturbance and trespassing. These are just a few examples. We have had blacklisted of suspected Communists during the McCarthy era and in the last thirty years there have been numerous campaigns engineered by Republicans to attack controversial artworks in order to undermine the legitimacy of state funding for the arts. In addition to that there are many cases in which religious fundamentalists have collaborated with politicians to foment media scandals that lead to the closing of exhibitions or the denial of funding to artists.

What I would say is that there is a difference between what happens in the US and what happens in Cuba. The Cuban government exercises much greater control over the public dissemination of culture. And its methods of sanction are more brutal. There are Cuban artists that have been sent to forced labor camps because they are gay, artists who lost the right to sell their work because they participated in an independent art show. There are artists who spend years in prison for writing a poem. There are artists that lost the possibility of performing, teaching, recording or doing anything with their music for years simply because they expressed a desire to leave the country. The worst part is that while Cuban artists may complain, they have virtually no legal means to challenge the State’s actions.

EN: Constitutional debate in Cuba has been marked by Decree 349/2018, or not? Can we say that this decree finds some precedent in Cuban legislation and that it does not constitute a mere occasional necessity but, rather, it continues the systemic practice of the regime?

CF: First of all, the official debate about the new Cuban constitution that took place in 2018 had nothing to do with Decree 349 and the protests against that decree. The official debate is the government’s way of pretending that the people’s views have been taken into account and consists of public events in workplaces and PCC offices. Everyone knows they can’t say anything significant in those contexts. The protests against Decree 349 are organized efforts by arts professionals to contest the new law. Several things about the law bothered artists: they did not want independent cultural endeavors to be criminalized; they did not like the idea of roving cadres of inspectors invading their studios and exhibition spaces and making decisions about what was or was not acceptable in art; they did not like that the government made laws for them without talking to them about the laws before they went into effect, and they saw the law as a step backwards to the methods used in the 1970s to suppress artists. There had been some hope in 2015-2017 that the rapprochement with the US under the Obama Administration would lead to greater openness in Cuban society. This decree signaled the opposite.

EN: You live in the USA. If you lived in Cuba do you think you would be developing the type of projects you have been presenting? It’s not easy to want to be an artist in a world that disregards him, but even less easy will be to want to be an international artist working from Cuba.

CF: I really don’t know what I would be doing if I were in Cuba. My life would obviously be very different.

Coco Fusco's work was presented at the Venice, Mercosur, Liverpool, Whitney, Shanghai and Kwangju Biennales, as well as Art Basel Unlimited, Frieze Special Projects, VideoBrasil, BAM's Next Wave Festival, Performa05, at New York Museum of Modern Art, The Walker Art Center, KW Institute of Contemporary Art and at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona, among other institutions. Fusco is the author of several books, among which we highlight: English is Broken Here: Notes on Cultural Fusion in the Americas; The Bodies that Were Not Ours and Other Writings; or A Field Guide for Female Interrogators. She is also the editor of Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas and Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self. His most recent book, Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba, was edited by Tate Publications and translated in 2017 by Madrid's Turner publisher [Pasos Peligrosos: El Performance y la política en Cuba]. Coco Fusco received several awards and grants, among which the Rabkin Prize for Art Criticism, Greenfield Prize, Absolut Art Writing Award, Herb Alpert Award in the Arts, Guggenheim, Fulbright, Cintas and Artists Fellowships.

+ info El País

+ info ArtnetNews

Photo: Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Amnesty International prisoner of conscience and artist.