Gabriel Abrantes: Melancolia Programada

Gabriel Abrantes exhibition at MAAT, Melancolia Programada, opened on 12 February, before the Covid-19 pandemic forced its current closure. Featuring both the artist’s earliest and most recent films, alongside a new VR commission and a suite — his first in 12 years — of paintings, the show offers a physical and psychic immersion into Abrantes’ cinematic universe. It’s a universe that plays fast and loose with familiar narrative devices and socio-political realities, colliding both to imagineer seductive, critical reveries through the ensuing explosion. It’s a world that takes amusement seriously, making Andy Coughman, the flying AI robot protagonist of The Artificial Humours, perhaps one of its best spokespeople, as he tells us, in his cute-as-hell voice:

“Wittgenstein said the most profound problems could only be discussed in the form of jokes. That logic didn’t have the power to resolve these questions. Truth be told, humour can be liberating, but it can also be a prison. There is an old story that says irony is a bird that has come to love its cage. And even though it sings in protest of its cage, it likes living within it.”

Abrantes’ world exists within the cage of our own one, and sings with ambiguous delight as it interrogates it. From behind the new bars of his quarantine in Lisbon, Gabriel talks us through the exhibition and his work.

Justin Jaeckle (JJ): Your schedule was due to have you away from Lisbon at the moment, where you’ve recently opened an exhibition at MAAT which has been the catalyst for this interview, but quite a few things have changed since that show’s launch in mid-February… So I’d like to kick things off by asking where does this email find you now, and why?

Gabriel Abrantes (GA): This email finds me back in Lisbon, quarantined! It has taken me a while to get back to you due to these chaotic covid-19 filled weeks. After the opening of ‘Melancolia Programada’ at MAAT I had traveled to NYC, and set up a studio there, but five days after I arrived, people were reported to be lining up to panic buy AR-15 automatic assault rifles all over the US. That frightening image, compounded with my lack of US medical insurance, rendered unenticing the prospect of being quarantined in a city of ten million during an epidemic while there was an international rush to hoard toilet paper.

JJ: Mounting an exhibition has some parallels to creating a film. Questions of editing (choosing which works to show) and montage (choreographing a viewer’s journey through the time and space of the exhibition, articulating relations between works through their sequencing and juxtaposition) are key to the way a show is experienced. Maybe a gallery could also be thought of as a studio. Maybe the movement from one room to another, one work to another, is like a jump cut, or shot-counter-shot… Maybe that’s stretching things… But in the first instance, I’d like to ask you how similar you felt your approach to creating the exhibition at MAAT was to the way you would approach creating a film, and if you could talk us thorough some of your decisions – particularly your choice of which films to present (the exhibition shows five, from your body of 23 works), what to show alongside them, and the path that you’ve designed for the visitor – both through the exhibition and through your body of work.

Gabriel Abrantes (GA):

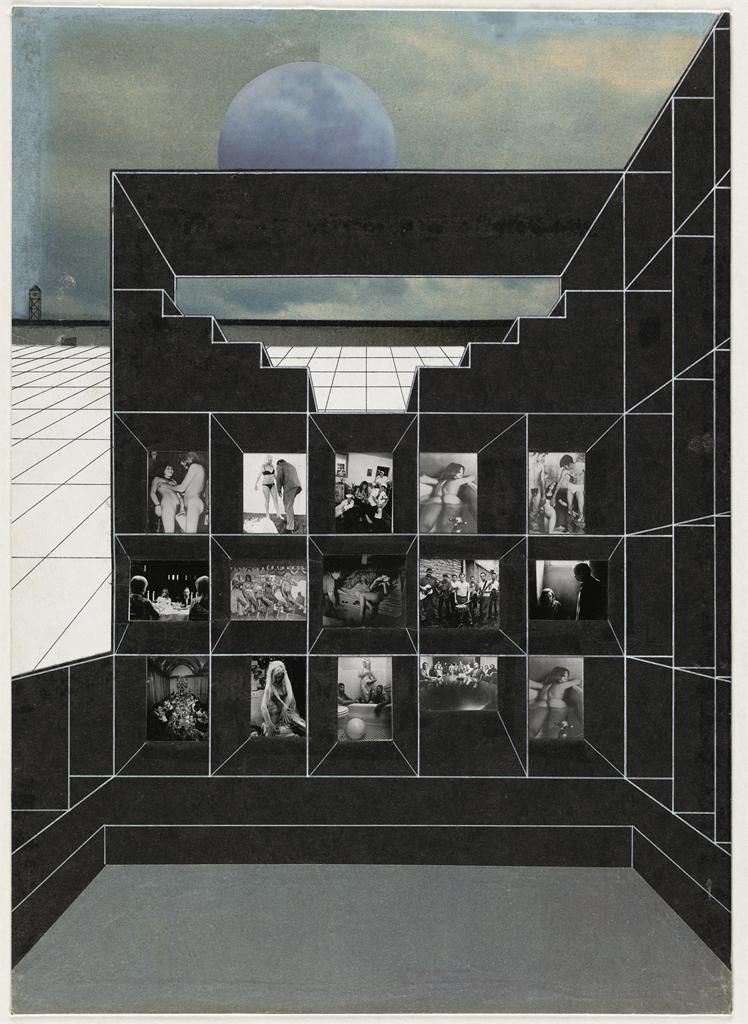

Rem Koolhaas studied film before he became an architect, and his 1972 thesis project from his time at the AA, ‘Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture’, explores the link between a programmatic organization of space and cinematic montage, and the mind-altering propagandistic potential of both discursive structures. I think it is an interesting parallel, and it led Koolhaas to a provocative proposal for his extra wide wall-cum-building-cum-human-transformation machine. It’s telling that in his project, the building is supposed to function only in one direction, like a film, with a beginning and end. The ‘voluntary prisoners’ enter the wall from the chaotic side of London, and progress through a number of chambers, including one where they watch mind-altering films, to prepare them for their new life in the utopian side of London.

It is wonderful to play with architectural programs in this way, as well as exhibition design, but I think the parallel works best theoretically. Exhibitions, like the one at MAAT, where the visitor’s experience is fluid, multi-directional, and the duration of time in each space is managed by the viewer, make it very different from a narrative film, that is watched beginning to end. Inês Grosso, the curator, did conceive the show with a directional flow, but we knew that we did not want to force that by gluing vinyl arrows on the ground, or suggesting a certain order to the visit. I think the fragmented and oneiric quality of the exhibition, felt by entering and exiting very distinct immersive environments, is really at the heart of the show. We didn’t want to organize the work chronologically either, so Inês and I were reacting to the space a lot, placing certain films, installations or paintings in certain spaces for a mix of reasons, that included conceptual programmatic choices, but also practical notions such as size, sound isolation, etc.

It was important to me to limit the number of videos, in order to have the duration of the show be accessible to a visitor — for instance, I didn’t want to have eight videos that would have a combined length of four hours. In terms of the choice of films, I wanted to re-install Visionary Iraq (co-directed with Benjamin Crotty) [2008] and Too Many Daddies, Mommies and Babies [2009] in their original format, inside of an immersive installation environment that mirrored the sets seen in the film, because it is how these films were originally meant to be seen and it is so rare to have an opportunity to show them this way, and having immersive video installations was more interesting to me than a sequence of black boxes with video projections. We also wanted to show Les Extraordinaires Mésaventures de la Jeune Fille de Pierre [2019] and A Brief History of Princess X [2016], because both of the films are about sculptures, as well as The Artificial Humors [2016], because these three are my most recent films. By showing them alongside Daddies and Iraq, it was a way to establish a contrast between work I made 12 years ago with work I made last year.

JJ: The exhibition opens with a wall of your watercolours — mostly gifts for friends, plus hand painted posters for the film works contained within the show at MAAT. There’s a scorpion painting its self portrait for your mum, a root vegetable grotesque for your dad for Father’s Day, gifts for friends, colleagues and collaborators like Natxo Checa, Alexandre Melo, Rui Brito and many others, expressed and embodied through animals, satyrs, and visual and verbal puns. It feels like this wall of watercolours functions almost like the credits or ‘thanks’ of the show (again a little like in a film) — a kind of nod to some of the social (and familial) relations that have gone into the development of your practice. Can you talk us through your decision to open the show in this way? Do you create similar sketches as part of your regular creative practice, or as ways of generating ideas for films? What’s your relationship to these handmade images?

GA: When Inês [Grosso] and I started discussing the work that would go into the show, I told her about this private body of work, these watercolors that I had been making over the last 12 years, as Christmas or birthday gifts. She thought it was great to bring this work into the show, considering it was not really part of my ‘practice’ in the sense that I had never shown it publicly, and that they were ‘minor works’ in the sense that they were works on paper, using techniques like watercolor or soft pastel, which have been traditionally regarded as inferior to the ‘great’ tradition of oil painting, and are often derided as decorative, or the provenance of a hobby ‘Sunday artist’. I also wanted to show them, as a way to short-circuit my anxiety relating to painting. I had not done a painting show for over a decade, and a big reason for that is the anxiety I have relating to painting, and especially relating to my work in the past, however unfounded it might be. By showing this private body of work, that wasn’t made to be shared publicly, this anxiety was thrown out of the window, in a way. The works were made innocently, as cute gifts for the people I love, and so they lacked any pretense— they have a naïf, sentimental, and infantile quality that contrasts with the preponderance of the films, installations and large-scale paintings.

I think you are totally right — it was also a way to thank a lot of the people that were close to me — family and friends, and collaborators. It was really important to open the show this way — in an unpretentious, personal and fragile tone, with delicate, silly, personal gifts — that sort of bared a personal sentimental side of me that can be harder to access through the films, installations, or paintings.

JJ: This wall of watercolour gifts also connects to the question of ‘Mutual Respect’ — with nods to the name of the production company you set up with ZDB and Natxo Checa (Mutual Respect Productions), the title of your 2010 book (and I am so thankful for all of the friendships I have made) and the title of your 2010 film with Daniel Schmidt (A History of Mutual Respect) — a film that somewhat queers the notion of how much respect or understanding is really possible between people and cultures, despite ‘best’ intentions… Many of your works are co-directed (another instance of mutual respect). Could expand on the idea of ‘Mutual Respect’ within your work — because it really seems key: both ‘genuinely’ in the way you create, as well as ‘critically’ as a subject, or idea, that gets deeply dissected within your films.

GA: The title of the short I directed with Daniel was ironic. In History, Palacios and Diamantino, Daniel and I focused on questions of ‘good intentions’ and how often these are founded on hypocrisy or ignorance — and how notions of multiculturalism and mutual respect are sometimes founded on the discourse of a dominant culture trying to subliminally justify its dominance through false promotion of values supposedly based on a desire for equality. In terms of the name of Mutual Respect Productions — it was also a jab at the notion that a company can be based on mutual respect, since often the tightest bonds between founding partners can give way to vehement legal accusations and the breaking of the bond of friendship. The title of the book “I’m so thankful for all of the friendships I have made” is grafted from a text that is facsimiled in the book, written by Ana Portal, a villager from Anelhe, that she wrote for the IEFP [Institute of Employment and Professional Training], in order to justify an unemployment subsidy, by discussing how she used technology, such as email and her cell phone, in order to work on my never finished feature film ‘Big Hug’ — so it is also a false sincerity — in the sense that it is just a quote. On the other hand, I love Natxo Checa and Daniel Schmidt, two of my closest friends, for example, so these titles are also a heart-on-sleeve declaration of that love.

The titles were supposed to have double meanings — you can read them as ironic quotes or as sincere declarations — sentimental expression and cold citation — which is also reflected in the title of the MAAT show ‘Programmed Melancholy’.

JJ: Do you see your collaborations with other directors: Daniel Schmidt, Benjamin Crotty, Ben Rivers, Katie Widloski, or, in the instance of Les Extraordinaires Mésaventures, for example, your casting of them (French director Virgil Vernier plays the museum guide), as part of a movement of sorts, or a cinematic community at least? Does the ‘mutual respect’ present in this network of collaborations indicate a certain shared approach towards what cinema is or could be, and if so, what would you identify as the common ground, or web of affinities, between you?

GA: I’m not sure. The collaborations came out of friendship, and this ‘network’ grew naturally. I respect their visions, and we share a lot of the same taste. They are people that I really enjoy spending time with. This loose network of affinities isn’t formal in any way — and it is quite fragmented — for example, Ben Rivers’ work is very different tonally from a lot of my work — but I love Ben’s work, and he is a friend, and vice versa – so we decided to make something together. But I think it would be futile to try to reduce such a motely and diversely connected crew to a single group of concepts.

JJ: Moving from cinema back to painting, I notice the paintings shown at MAAT are all from 2020. Were the paintings made specifically for the show? Could you talk us through both this body of paintings in particular (which share a unified aesthetic) as well as the place of painting in your work and creative processes more generally these days?

GA: When Inês [Grosso] invited me to show, I really wanted to make new paintings. I had not done a painting show since ‘20-30 Experiments in Moral Relativism’ at Galeria 111 in 2008. I had made a few paintings, and only publicly exhibited two of them in the intervening 12 years. What excited me most about the show at MAAT was that I could use it as a platform to force me to propose something new through painting. I started developing paintings, and it was a circuitous voyage, which almost ended (during the most frustrating moments), with me giving up on this new set of paintings, and therefore most likely giving up on painting for good.

Painting has always been really important to me, ever since I was a child, and the fact that moving image work became the bulk of my practice was never something that I was happy with, but film production has an abysmal power, sucking me into whatever project I start on, making it difficult to take the time (and headspace), that is necessary to get involved in the more tranquil, solitary and often ludic practice of painting. As I was developing this new series of paintings, there were a lot of hiccups, disasters, disappointments. There were paintings I was making that I have now destroyed, and some that I haven’t destroyed but frankly should. I made a very awkward painting of a buck-toothed octopus listening to a cross legged satyr playing a guitar on a beach, that is still in my studio, and my partner Margarida laughs every time she sees it and says ‘looking at that, one would never guess you were an artist’. I knew when I started trying to make this series that I wanted to make paintings based on imagery that I would create digitally in the 3D modeling program Maya, which I also use for my films, and that IrmaLucia (a postproduction house) used to create the characters in my films, like Coughman, Jeune Fille and Jean Jacques. It took a while to get to the form – to create the characters that I was interested in, characters that were a mixture of fragmented, horrified, discombobulated, awkwardly pathetic, melancholic, funny and cute.

JJ: Your work dances between reception and dissemination in the spaces of visual art and cinema. You’ve shown with commercial galleries for many years (currently Francisco Fino, and in the past with Galeria 111), and I notice your films are available on the market as editions of five. At the same time, the films premiere at, and navigate, the film festival circuit to great success, where they’ve won awards at Cannes, Locarno, the Berlinale, been honoured with retrospectives at BAFICI and Belfort, and achieved widespread distribution. Whilst it’s not so unusual for artist or experimental filmmakers to oscillate between these contexts, it feels like something different happens with your work – work which often offers a provocation towards the kind of (often more austere) poetic ethnographies, essay films or formal experiments that are ‘allowed’ to exist in between these worlds. How do you feel your films operate in each of these contexts? Do you feel the films are read, or play, differently within the cinema and art worlds?

GA: I started making moving image work as an artist, when I was at art school, and I really wanted to use cinema, and, more precisely, narrative cinematic forms, as a way to react against what I saw at the time as a rote ‘fragmented’ or ‘poetic’ tradition of fine art moving image that had branched out from structural and experimental cinema of the 60s and 70s. I was inspired by the pop art vein of underground cinema, namely the films of Andy Warhol and Kenneth Anger, but was also invested in playing with rigid linear narrative codes. In doing so, I was trying to move beyond what seemed to me as an overreliance on the postmodernist discursive allowance for fragmentation, which seemed to me like a pretentious way artists hid the fact that they did not have much to say.

I do think the work plays differently in the gallery and the cinema. I get annoyed when I encounter a longer narrative work in the gallery, and since I make longer narrative work that is shown in galleries, I am probably oversensitive to it. I think Princess X works well in the gallery because it is so short, and Visionary Iraq and Too Many Daddies work well because the films have major facets that are immediately absorbed after watching only a minute of the work.

JJ: I’d like to also ask you about your own role, as a performer, within your films. In the MAAT show we see you and Benjamin Crotty play all the roles in Visionary Iraq, and your monologue guides A Brief History of Princess X, and you’ve frequently appeared as an actor across your wider work. I’m interested in how this maybe talks to lineages of performance (in Visionary Iraq we see you and Benjamin lounging in scenes reminiscent of Lou Reed and John Cale in Warhol's Factory), and wonder if your appearance within your own films might be another bridge between them and the artworld. How do you feel your work is affected by your own appearance in it? And do you feel a connection to performance practices?

GA: We initially thought it was funny to act in our own work because we were horrible actors, and these amateur performances added to the camp affect of the films, and I think that does come out of an appreciation of camp amateurism in the work of Anger and Warhol. The aluminum ‘gallery’ set in the film is a reference to Andy Warhol’s Factory, and Ben and I were playing a parody version of Reed and Cale.

In 2001 I was an impressionable young art student, making films at Cooper Union, in NYC, when Matthew Barney had his Cremaster Retrospective at the Guggenheim. That show, no matter how roundly lambasted it was by everyone from the New York Times to the Village Voice, to the art students and art faculty at my school, was supremely inspiring to me, especially in how it self-reflexively played with art practice as a form of social theatre – how the artist is a player in a role, within a make-believe world with make-believe rules and customs and rituals. Also thrilling to me was the use of performance as a way to reiterate the artist’s role on the stage of the art world. These notions were enticing to me, and inspired me to perform in my work, as a way to underline certain problematics relating to authorship, identity, agency.

JJ: The MAAT show focuses on a selection of five films (made between 2008 and 2019) that share a certain attitude, a kind of sharp effervescence (if that’s not a contradiction) and camp criticality, and, interestingly, are maybe some of your least ‘Portuguese’ productions in relation to both their tone and subject. There’s a body of films from a certain time, 2010-13, like A History of Mutual Respect (2010), Palácios de Pena (2011), Liberdade (2011), Fratelli (2011) and Ornithes (2013), that feel in some ways more ‘Portuguese’ — both in terms of certain subjects, and, maybe more interestingly, in terms of their form; those films in particular share a certain kind of lyrical poetics, pacing and construction that talks to what might be commonly identified as a specificity of Portuguese cinema (and ‘talks to’ feels like the operative word here, as they also play with the expectations that engenders). Both your earlier and more recent films to these, whilst sharing a clear authorship and set of interests with them, feel like they have a slightly different kind of energy and approach – a spiky density of references and ideas that feels more like a détournement of tropes from TV, comedy and Hollywood, that looks to seduce us in a different way and also, in the more recent works, sees you playing ever more with CGI in a mesh with your go-to Super 16mm. So this perhaps is a two part question: asking you to reflect on the place of Lisbon and Portugal as an influence on, and topic within, your work in the first place, and then more broadly asking if you identify a change in the tone, subject and approach of your work over the arc of the last ten or so years.

GA: I grew up in the States, and although my parents are Portuguese, my culture and psychic makeup were mostly molded in US suburbia. My relationship to Portugal was always that of an outsider, of an immigrant returned, and my work reflects this. A film that you don’t mention, but that is significant in these terms is Taprobana [2014], which is a short film that depicts Camões, Portugal’s central poetic figure, as a Falstaffian antihero, tragically oblivious to his own baseness. Taprobana is a film unlikely to be made by someone who grew up in Portugal, who most likely saw Camões as boring, having been forced to read him as a teen. That, or to overly revere Camões as the foundational poet of the Portuguese language, to the detriment of a critical stance that would reveal him to be an artist very much of his time, whose work, no matter how sublime the metaphors and transcendental the imagery, was tantamount to misogynistic and racist colonial propaganda.

The films, seen together, have a strange quality – they can be assembled and presented as a unified body of work, with common themes, tones, aesthetic tropes, references, but at the same time they can be seen as fragmented and idiosyncratic: a frenzied array of artistic spurts, taking off on myriad conceptual, collaborative, and narrative tangents.

JJ: The exhibition’s title — Melancolia Programada — also talks to Portugal, almost feeling like a message to the country or a summation of a national attitude. You avoid the word ‘saudade’, but this idea of ‘programmed melancholy’ definitely flirts with the concept; as well as, maybe, interacting with questions of how the identity of Lisbon is perceived by the growing number of tourists who visit it (and MAAT). Can you talk us through the idea of the title of the show?

GA: I’m not sure what led me to the title, but I like your reading.

The word ‘melancholy’ actually came from something Alexander Melo said after watching the Jeune Fille film. He said, with his telltale droll irony: “Oh, but it’s so melancholic. We had no idea you were such a sad little boy!” And I remember being surprised by the word melancholy, which I didn’t associate with my work, and didn’t associate with Jeune Fille. But after he said it, it seemed true that Jeune Fille basked in melancholy. And as I was thinking about the Pagliacci of the Comedia del Arte that inspired the harlequin patterns that show up in the paintings, who are pathetic clowns, tragic while making jokes, or I thought of characters and subjects in my films like Andy Coughman, Jeune Fille, or the sculpture ‘Princess X’, I realized that all of these objects (sculptures and robots and clowns) were portraited as sad, and that that was what was funny about them. In the case of Andy Coughman, he is literally programmed to be sad as a testament to his humanity. I thought that was both funny and an interesting thread that tied all the work together: a programmed melancholy – also present in Daddies and Iraq, works that are deeply inspired on the programmatic histrionics and rote sentimentality of daytime soaps.

JJ: Related maybe to the notion of melancholy, is a sense common to many of the films on show at MAAT, and throughout your wider work, that articulates something like the thin, tragic line between ideological or political conviction and narcissistic solipsism, between belief and naivety… The curiosity of the statue and her burgeoning interest in politics in Les Extraordinaires Mésaventures results in her (literally) falling to pieces and running away for an escapist Instaholiday with her hippo love interest; the incestuous siblings of Visionary Iraq see their desire to ‘change the world’ thwarted by their father’s Shock Doctrine style exploitation of the war for profit; the gay couple of Too Many Daddies abandon their attempts to save the Amazon, and with it the human race, to start their own family as a substitute for their need to believe in something… The ‘refugiadinho’ of Diamantino also comes to mind here. There’s this idea of the ever-imminent failure of best intentions, and maybe how such intentions are always subject to and overwhelmed by greater forces of libidinal desire, that throbs throughout your work. Can you expand on this?

GA: I have always been skeptical about good intentions, self-righteousness, and a do-gooder attitude, all of which might be ascribed to hypocritical façade, naïf ignorance, or malicious ploy. I think my films reflect this skepticism towards a prefabricated flag-waving missionary-style morality that seeks to shame others, while self-promoting and self-congratulating. The hypocritical arrogance of most supposed acts of charity inspires in me reactions that range from eye-roll to full on revulsion. This gut reaction has definitely been the starting point for a lot of my work. I think charity and good intentions often function as a mark of distinction for the privileged, and I have a hard time swallowing that.

JJ: I want to also ask you about generosity. Films are peculiar, almost dictatorial things in that they demand a specific length of time is spent with them — a film’s contract with its audience is one of an imposition of duration. Films, or filmmakers, at least on the auteur circuit, can often exploit this contract, and forget it might mean the audience deserves to be given something juicy in exchange and thanks for the time demanded of them, or at least to be seduced into this time being enjoyably spent. In your work seduction is ever present, which I see as a form of great generosity. The films want to seduce and entertain us, whilst often dealing critically with desire and entertainment themselves as topics. What role does the audience play in your conception of your films, and perhaps more broadly in your understanding of cinema? Can you talk us through your interest and means of employing, maybe hijacking, tactics of entertainment — both in terms of form and storytelling — which you often re-purpose for more complex, critical ends?

GA: I was initially led to make films after taking Jim Hoberman’s Cinema History class. What I got from this class was that cinema was a popular medium that functioned as a myth-making machine, a magic factory, forging the yet uncreated consciousness of its time. Hoberman showed us that grand side of cinema, but he also showed us that it did all that as a vulgar debased medium; cinema is an aesthetic cur — a medium made up of a hodgepodge mix of sound, dialogue, performance, music, narrative, image — as far from the modernist fantasy of a ‘pure’ essential aesthetic form as possible, a form of base entertainment, with origins in the burlesque theatre, originally marketed to the lowest classes of New York at the penny arcades and Nickelodeons, deemed too base to be appreciated by elevated society. This concept — of the grand industrial myth-making machine, that was also the basest form of entertainment — was what made me fall in love with cinema, and invest my practice in working with a medium that was primarily seen as a form of popular entertainment, and not as rarefied culture, to be wielded as an emblem of distinction by the elites (cultural or economic) that ‘got it’ or had enough money to literally buy it.

But it is funny, because cinema is transforming so quickly, and the way it has existed for the majority of the XXth century seems to be dying, as global eyeballs make a total migration online, to social media, gaming and streaming. So I’m starting to try to play with these mediums as well, with long form serialized storytelling, virtual reality, and video games. At the MAAT show, Coughman’s Lament [2020] is the most recent work, commissioned by the museum, and it is a piece that points towards a language and medium that I am more and more interested in exploring — immersive virtual worlds, gaming, and online media.

Justin Jaeckle is a curator, writer and editor working across contemporary culture, art and the moving image. He is a programmer, since 2016, for Doclisboa International Film Festival. He has previously curated programmes for and in partnership with numerous cultural institutions, including Tate, Design Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum, Auto Italia and Cinemateca Portuguesa. Since 2008 he has curated the bi-monthly Architecture Foundation/Barbican series Architecture on Film. He has written for titles including Art Review, Frieze, Octopus Notes and Wallpaper*. He studied Fine Art at Central St Martins.

Gabriel Abrantes, Melancolia Programada, vistas gerais da exposição no MAAT. Fotos. Bruno Lopes. Cortesia do artista e Fundação EDP.