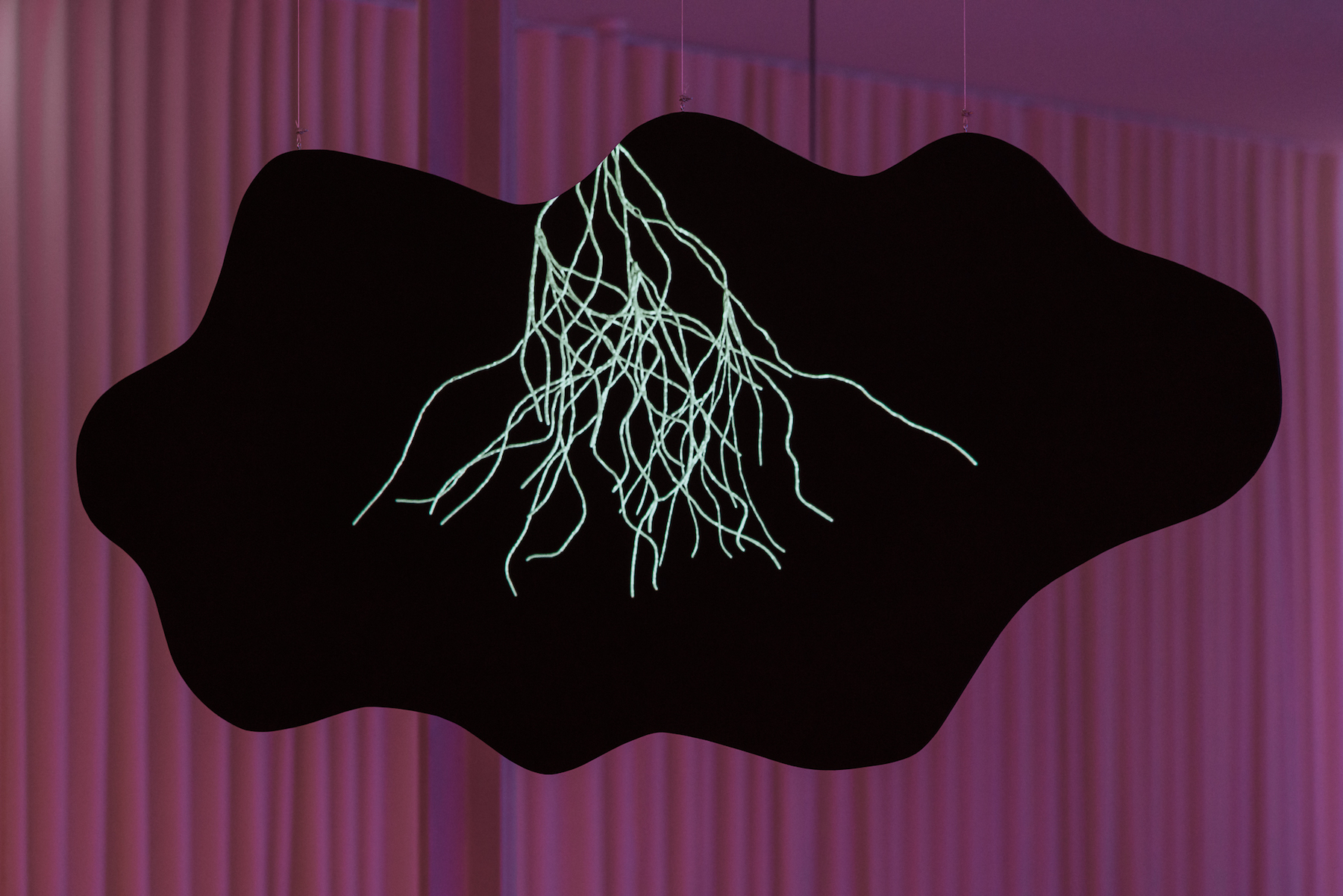

Diana Policarpo: Nets of Hyphae

Diana Policarpo is a visual artist and composer. Her artistic activity is developed within visual arts, electroacoustic music, and multimedia performance. In the context of her artistic practice, she researches power relations, pop culture, and gender politics, juxtaposing the rhythmic structure of sound as tactile material with the social construct of esoteric ideology. She creates performances and installations in order to look into experiences of vulnerability and empowerment associated with acts of exposure in the face of the capitalist world. Nets of Hyphae is Diana Policarpo's latest exhibition, curated by Stefanie Hessler at Galeria Municipal do Porto, on view until 14 February 2021, after which date will be presented at the Kunsthall Tröndheim, Norway (from 11 February to 18 April), co-produced by the artist. A book will be published by Mousse Publishing in conjunction with the latter exhibition. The following conversation is centred around Nets of Hyphae.

Eduarda Neves (EN): In Nets of Hyphae, you establish critical relations between ergotism, reproductive politics, and alternative epistemologies. The speculative connections you draw upon seem to work as strategies of political convergence to seemingly distant realities. Do you agree?

Diana Policarpo (DP): This is an extensive project I started in 2019 which has materialised in different ways. The exhibition Nets of Hyphaea and the homonymous book mark the first moment of it, presenting several works that function as constellation of diverse, interconnected narratives which examine the presence of the ergot fungus in our society throughout history. I started developing this project from an analysis of the complex life cycle of this alien fungus, the way it contaminates the reproductive system of plants and people with a uterus, and reading about mythologies and biographies associated with psychedelics that proceed from this hybrid plant. Hallucinations, trance states, animism, and contamination are ever-present themes in the various, intertwined narratives within this exhibition.

Illnesses caused by the ergot fungus, which contaminates entire cereal plantations—of rye especially—have had a great impact on human history and agriculture, having brought about devastating epidemics. However, the ergot alkaloids, the fungus's toxic components, have been used for therapeutic, spiritual, and medicinal purposes for many centuries. Midwives used this fungus as main resource for assisting in childbirth and excessive haemorrhages, and also as an abortifacient. The use of ergot for (pre-LSD) therapeutic purposes and its contamination via consumption of cereal went on for a long time, despite being studied only after a period of large-scale impoverishment and persecution under the allegation of witchcraft across Europe, or after well-known events such as the Dancing Plague, St. Anthony's Fire, or ergotism (which inspired the theme of Hieronymus Bosch's Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony), the bread riots, and so on. I was interested in various stories that approach herbology, magic, and health as integral part of the social and political lives of women in their communities during the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

EN: In the work Bosch's Garden, you draw on, on the one hand, ergotism and alchemy, and fertility on the other. Should it be regarded as a hermeneutic possibility considered within the context of this project, which convergences do you intend to establish between the toxic ergot alkaloids, their powerful effects on the circulatory and neurotransmitter systems, and Bosch's work Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony?

DP: Bosch was always on my mind for this project, in the sense that the triptych you mention could establish an interesting dialogue with the other works presented in the exhibition. Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony is a painting I'm rather familiar with since my childhood days, for I lived close to the National Museum of Ancient Art, in Lisbon, and my nan used to take me there. It's a sort of cultural mosaic of intoxication, and it symbolically represents the causes and cures of ergotism-related hallucinations.

After getting the OK from the National Museum of Ancient Art, I started working with João Pedro, with whom I'd already previously collaborated, on a digital animation for three projections that could complement my text. Not unlike the other videos in the exhibition, it's a short one, but it resulted from a rather long image preparation process, as a great deal of the painting's details were animated. Infected Ear, the other 3D animation in this exhibition, is also a digital animation about the mutation of the several bodies (plant, animal, and human) during the lifecycle of ergot, and was created with another friend of mine, João Cáceres Costa, with whom I'd already collaborated on my previous project, Death Grip.

Medieval painting contributed significantly to create the medieval imaginary, the daily life, the collective and individual existence, and the meaning of the human and non-human metamorphoses that populate many of the scenes. Alienation, disorder, and madness are some of the effects of a so-called abnormal, variously designated behaviour. Therefore, ergotism is marginal by nature, as it's always had some negative aspect closely linked to witchcraft. Its territoriality and cultural codification are structural components in the history of psychoactive substances. At that time, a permanent state of contamination was quite usual, on account of the rye fungus, through beverages or bread, the latter being the main source of nourishment for the poorer classes.

We ought to look for the cause for this gloomy association both in science and in culture.

I wrote a text about the symbols, causes, and cures of this illness that is represented in the triptych. It's a text that also seeks to guide the gaze of the viewer through its most important symbols—fire and alchemy, both essential to the processes of synthetisation and transformation from one state to the other.

This video addresses the symbolism of fire, potions, and cures. My interpretations of this painting point to the symbolism of the characters, witchcraft, alchemy, and medicine. Historian Laurinda S. Dixon, who wrote extensively on Bosch's work, has stated that this painting makes a clear reference to ergotism.

EN: Nets of Hyphae puts forwards the confrontation with sexual freedom and the struggle of women for birth control during the transition to capitalism. Do the history of women and their role in the struggle against feudal power, calling into question the dominant sexual norms, as studied by Silvia Federici, populate this exhibition?

DP: Federici is a very important philosopher, and her essays Wages for Housework and Caliban and the Witch are essential for Marxist feminism. I'm solely interested in a feminism that is anti-racist, anti-capitalist, that fights for transgender and sex workers' rights. Bodies always draw our attention to reciprocity and to what we have in common, while property and labour always draw our attention to inequality and to what separates us. The video The Oracle explores that need to examine magic practices with class consciousness and to put them at the service of a transcendence that is more collective than personal transgression.

Shortly after I moved to New York, the Central Park statue of John Marion Sims was removed. John Marion Sims is considered "the father of gynaecology," thanks to the suffering he subjected black women to—among them Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey, who went through countless non-consensual experiments without anaesthesia. Mass hysterectomies are still performed today in American immigrant detention centres against their will. There are many other cases, but the problem lies really in the fact that some bodies are still the means to fix the bodies of others.

EN: As regards ergotism, the symptoms included a burning sensation in one's limbs, trance, hallucinations, and even miscarriage. In this context, you intend to show us that midwives and physicians have used ergot to speed up labour or to cause miscarriage for many centuries now. However, it is medicine itself that, by using sclerotia for medicinal purposes, maintains a general distrust of the therapeutic use of plants and certain types of drugs. Do you analogically suggest that we must subject the body, thus dominated by a certain orthodox normalisation of sexual health and by the political-symbolical colonisation of clinical-gynaecologic knowledge, to theoretical reelaboration?

DP: I've always been interested in plants, and I grew up with a knowledge that was passed down through several generations of my family. Upon my return to Portugal, I was told ergot had been very important for the economy of various regions in Northern Portugal and Galicia. During the Russian War and the Spanish Civil War, Portugal was in charge of exporting pharmaceutical ergot worldwide for almost two decades. The border between Portugal and Galicia was very important for the circulation of this natural resource, also due to its proximity to the Port of Vigo.

It was fascinating to learn about the traditional designations this fungus has been given in different countries, the agricultural rituals and work songs, the export process of this natural drug to international pharmaceutical corporations, including the Sandoz labs in Zurich, where LSD was first synthetised, in 1943, by Albert Hoffman.

EN: You show us some footage of biohacker Paula Pin working in her laboratory, in Galicia. Can you tell us about this experience and clarify the unique operativity of these gynaecological technologies? In what way do they claim other subjectivations that are capable of casting aside naturalised and universalised historical devices surrounding class, gender, and race?

DP: I became aware of Paula's work through a Barcelona-based journalist that specialised in sexual health, social rights, and criminal investigations. Paula Pin is an artist and researcher, and has developed amazing DIY gynaecology work with a biohacker collective on the outskirts of Barcelona. They used to live in a cooperative community, a sort of post-capitalist, eco-industrial colony located in an old textile factory, where they developed workshops with the purpose of decolonising the body, exploring plant-based vaginal and uterine medicine, DIY lubricants, and various types of more ergonomic objects, from sex toys to 3D-printed gynaecological tools.

Biohacking enjoys a long history, having used traditional medicine and various types of technologies and creating tools accessible to other people. Decolonisation and access to knowledge, as well as DIY and care practices within the community, are essential to this activity. When I first reached Paula, we promptly realised we shared a great deal of common interests and wanted to work with each another. We were very interested in collaborating, but there were many limitations due to the pandemic, so I ended up travelling to Galicia to meet her in person. We made this video in a few days, before Spain went into another lockdown. The video was entirely filmed inside Paula's van, which is also her mobile lab. Last year was rather challenging, since I had access to none of the labs of the institutions that supported me throughout this process. All was carried out by videocall.

As access to technological devices increases and places where to use them proliferate, technology becomes progressively capable of offering ever more viable alternatives.

There are lots of people who aren't able to get quality health care and medical treatment on account of poverty, cultural differences, gender identity, race, sexual orientation, and so on. Biohacking seeks to help and create accessible tools for these people, whose needs will probably not be met by their countries' health systems.

Several interesting projects are underway, like that of an American artist and biologist who is trying to facilitate hormonal therapy using genetically modified plants, such as tobacco, to produce oestrogen and testosterone. In another project, they are currently creating insulin for diabetics from fermentation, this being an example of one of the most expensive drugs in the USA, with people's lives depending upon the daily dosage of it.

EN: Video, digital animation, drawing, and historically situated visual narratives prevail in the exhibition. However, the sound installation and the plastic nature of light manifest a sort of structuring force around which all other elements unify into a space-time, I'd say, of a warm, affective intensity. Notwithstanding the expressive vigour of light, Kounellis's words on Caravaggio and on the revolutionary power of shadow came to mind as I walked through the exhibition. I feel like there's a certain poetics of obscurity and even an appeal to some silence that gives this work a ritualised dimension. On the other hand, in this second project in which you collaborate with composer and multi-instrumentalist Edward Simpson, you divide the composition into parts that correspond to the lifecycle of ergot. Can you explain this process and how it works as a sound landscape that potentiates a certain atmosphere of unreality?

DP: As the curator, Steffi Hessler, and I were developing the exhibition design, we thought right away of hanging all videos, drawings, and AV equipment, as is the case with sound, which is played on a number of speakers. We were very interested in the notion of gravity and the immersive feature of space, both visually and acoustically. Right from the start, I'd thought of displaying short videos accompanied by the filtered lighting and the sound landscape that pervades the whole venue. The transparency of the drawing supports and the changing of colour in some parts of the gallery were very exciting to work on, as it's a very long, triangular room.

It's important that people are able to see and listen to all the works during their visit, hence the looped brevity of all texts, videos, and sound, so as to enable the visitor to step into the story at any given moment. Lighting is a nuclear element in all my installations, and it's thought out conceptually in keeping with the symbols and temperatures that are thought out for each work. I was also interested in the idea of contamination and the artificiality of space, depending on the area and on the videos on display in it.

The sound installation Drift ended up being the component of this exhibition that underwent the most transformations last year. It was a very difficult year to access or research in labs or institutes, due to the pandemic. Even with such limitations, I worked with the Técnico microlab, in Lisbon, and with the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Porto to create images that could come in handy for the drawings and the score. When I first contacted Ed Simpson to collaborate with me, we thought of a 16-channel sound landscape that could activate the entire gallery. Ed suggested that we used a Buchla synthetiser, and I also wanted to try out a MIDI bio-sonification module that captures sounds and frequencies directly from fungi or plants.

The sound composition was conceived for three different moments, and it's always comprised of sounds that gradually change across the exhibition space, depending on the works we're seeing at a given time.

Eduarda Neves has a degree in Philosophy and a PhD in Aesthetics. She is a professor of contemporary art theory and criticism, an area in which she has published various works, and an independent curator. Her research and curatorial activities cross the fields of art, philosophy, and politics.

Translation PT-EN: Diogo Montenegro

Diana Policarpo: Nets of Hyphae. Exhibition views at Galeria Municipal do Porto. Photos: Dinis Santos. Courtesy of the artist and Galeria Municipal do Porto.