Great Moments: Eduardo Batarda nos Anos Setenta

Great Moments, Eduardo Batarda nos Anos Setenta is the newest addition in the history of anthological exhibitions dedicated to the work of Eduardo Batarda (1964, Coimbra). Taking place at the Fundação Arpad Szenes-Vieira da Silva with the collaboration of the Fundação Carmona e Costa, the exhibition covers the artist’s work during the 1970s. It represents a new chapter that should help clarify the artist's intricate research, a step ahead towards “understanding.”

Instead, the exhibition curated by João Mourão and Luís Silva probably produces the opposite effect, twisting the meaning, even possibly creating a more complicated situation. I know, it may seem paradoxical: Great Moments is a retrospective focused on the artworks produced in a brief period of time, and hence it should dispel all doubts, discover all meanings, but that is simply not the case…

The visitors’ approach to the exhibition, especially those unfamiliar with Eduardo Batarda's work, is perfectly arranged to create suspense. The public, taking the path leading to the second floor of the foundation, is aware that they are not in a classic museum: small rooms with low ceilings, everything suggesting a small exhibition with a few emblematic works, probably a so-called “gem,” but certainly not an anthological exhibition like the ones we usually expect.

The entrance of Great Moments certainly confirms the first hypothesis, with its few well-spaced canvases, realised in the early 1970s (1970–1972, to be specific). These works perfectly conceal what the visitor is going to encounter in the next rooms, waiting on the other side to take our breath away, like a hunter preparing his shot.

What catches the eye in this first room are those more "abstract" works, which look like empty comic strips, marked by some scratches. They resemble folds in a fabric that do not let anything show through, hiding what rests behind them. At this point, we have reached the crossroads, and any direction we take does not matter, as there is no predefined path, no escape. We have now fallen into the hunter’s trap.

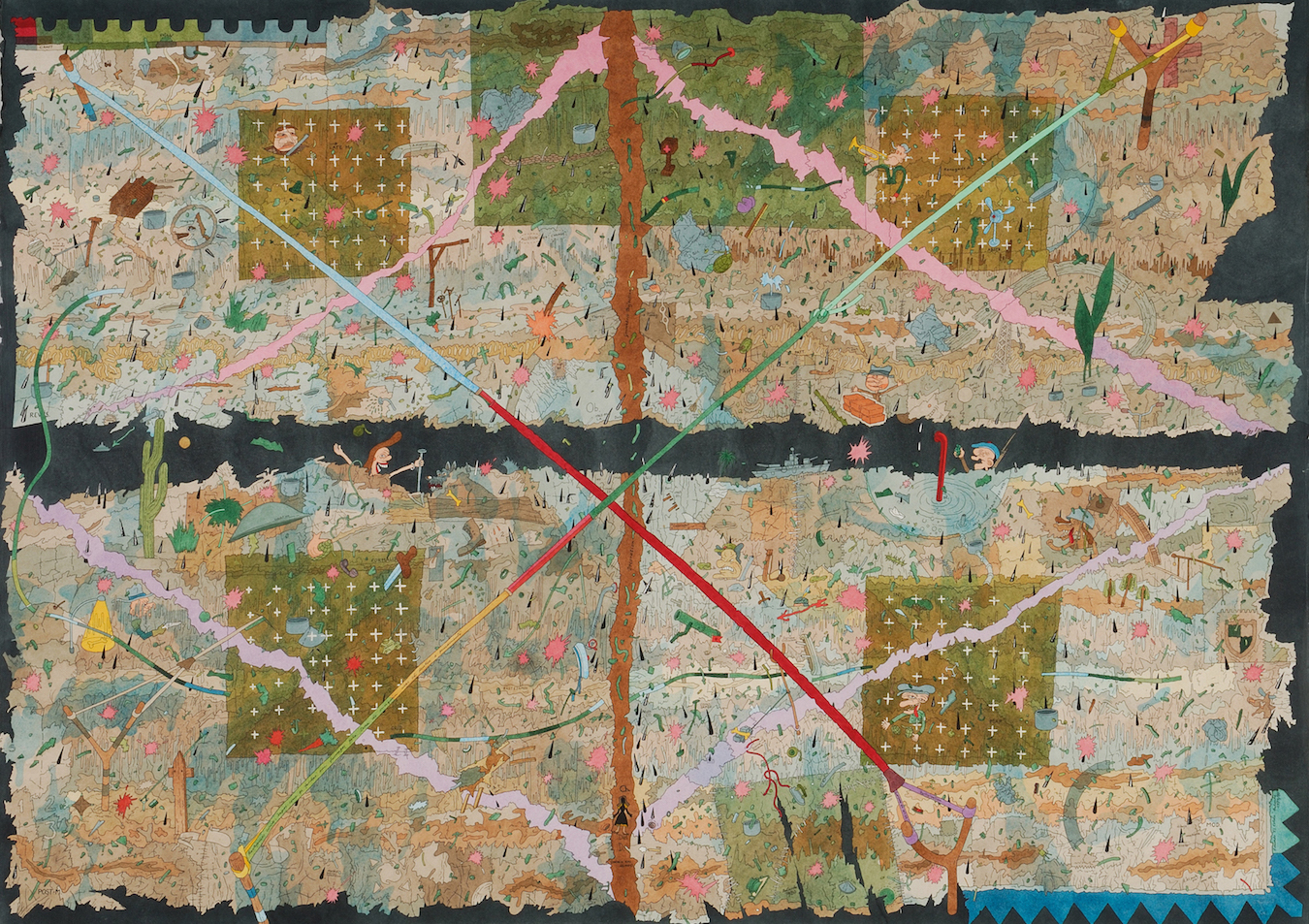

What comes in the following rooms is an assault by a wide range of meticulous, well detailed images, full to the brim with shapes and eye-catching colours.

At first glance, we are probably able to recognise just a few of the elements in the visual imaginary created by Batarda: there are body parts (many noses depicted in every possible way), historical/artistic characters, geographical maps, sex scenes, copious amounts of text, animals, vegetables, skulls.

Once again there is a trap waiting for us. The chaos generated by these images seems to have an “explanation” only in a hallucinatory state. These “comics” have forgone any typical linear narrative and clear composition, reaching the state of no meaning. All the elements depicted have no logical connection to one another. However, as is usual in these problematic situations, taking some time and physically approaching the work will help bring about a clearer vision. This engagement could be partly suggested by the spaces of the museum itself.

Indeed, the scale of both the rooms and the works seems to have been specifically conceived to invite the viewer to come closer, to enter into the details of the works. The invitation is also clearly expressed by the artist in No chão que nem uma seta, 1975, where, in an explanatory note written within the work, we read: Isto é uma pintura. E uma pintura de ver ao perto. É por isso que aqui estão as pequenas. (This is a painting. A painting that must be seen up close. Hence the small print). Some other times, it could happen that, while reading the writing in the artworks, you simply are insulted, as in the case of one work’s “Testa di cazzo” (which means “dickhead” in Italian. You’re welcome).

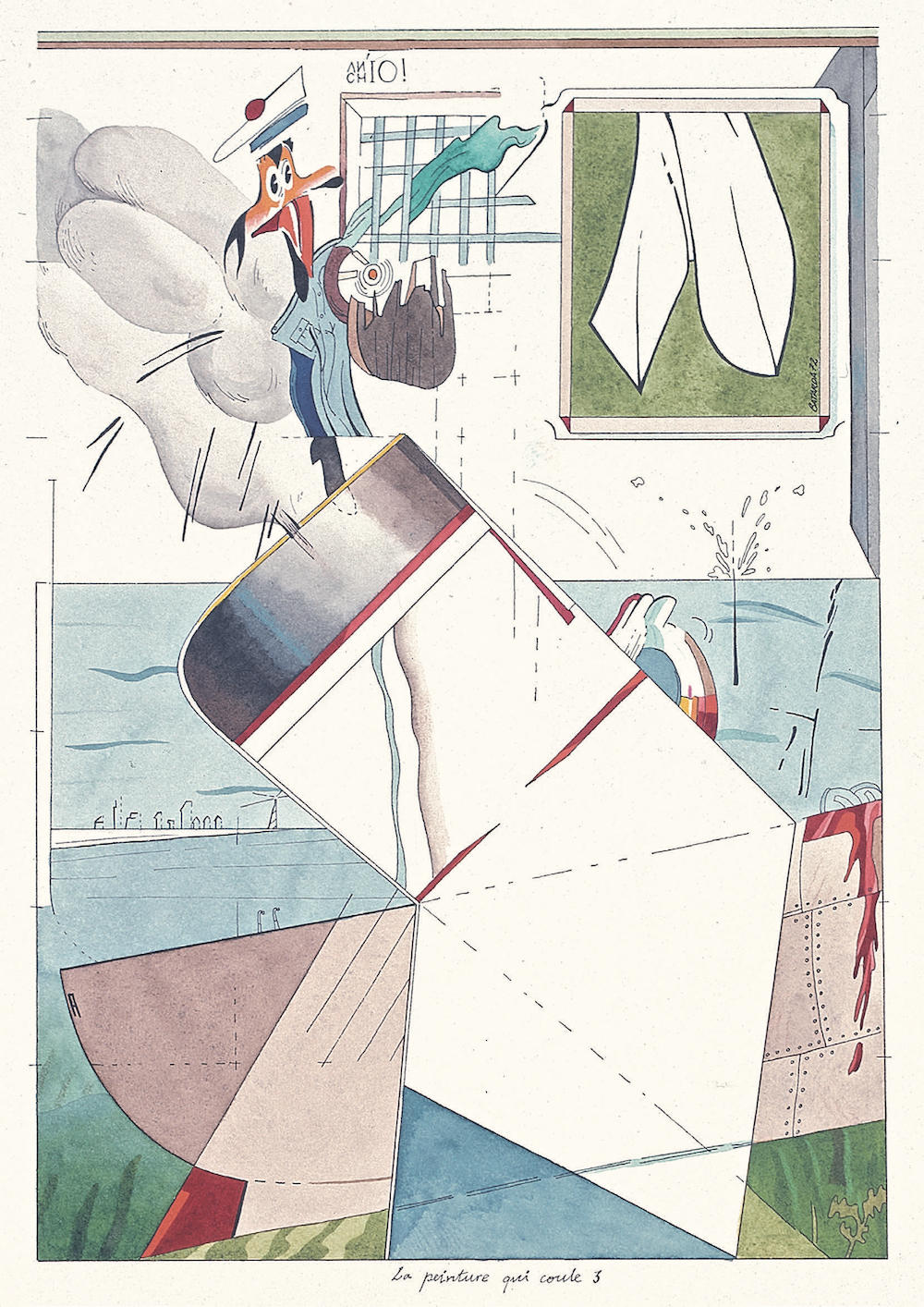

Various guidelines emerge from this close analysis, also suggested by the titles of the works themselves. These Great Moments created by Eduardo Batarda reveal an underlying fascination with the absurd structured through disturbing and obscene images, with clear pornographic and sometimes wicked references. These scenes, such as those depicted in The Hidden Chicken, 1972, or Double Act, 1973, are deliberately conceived to hit the bourgeois morale and “good taste.” Characters like Otto Dix in Nova Realidade (inspiração germânica) ou: Recuerdo de Otto Dix, 1975, on the other hand, are clearly represented in a caricatural, vaguely grotesque way, denoting an affiliation with the edges of the social ladder.

Another line we can read in these watercolours is the ironic attitude connecting the entirety of Batarda's production of the 1970s. Exactly like satirical cartoons, works like Great Moments in Self-Expression (Ecole Bolognaise), 1973 — which gives the exhibition its title —, and Salade aux artistes-peintres, 1972, want to be a public mockery of artistic expressions and of the general culture of the time, not just the Portuguese one. In accordance with the events taking place all over the world during the same years, starting with the movements of dissent in America at the end of the 1960s, these works by Eduardo Batarda direct an open question at the political, social, and cultural models as well as at all the established forms of power. However, this attitude seems to aim not at setting the stage for new structures, but rather at taking on a form of rebellion with no programmed logic, for its own sake. It becomes difficult not to consider these works as an early expression of a punk soul.

The path that Italian comics took around the same years (late 1970s / early 1980s) comes naturally to my mind as a parallel. What dawns on me first are the magazines Cannibale and the later Frigidaire, which collected all the technical and narrative experimentations carried out by the great Italian comic authors of those years. Looking at Batarda's works, the similarity with Tanino Liberatore and Andrea Pazienza becomes clear, in particular if we look at their most emblematic characters, respectively Ranxerox[1] and Zanardi[2]. Their way of making comics is disturbing, “sacrilegious,” filled with graphic violence and a fair amount of pornography. They are the perfect expression of a deliberately transgressive counterculture, which highlights the exasperation of an angry and destructive generation.

Similar to the Great Moments of Batarda, these comics are fragmented and incredibly detailed. They do not follow any particular trend, but instead mix them all together. Rejecting the objective sense, the reality that emerges is extremely disconnected, structured in many levels where it becomes impossible to satisfy that human desire for full comprehension.

The contemporary attitude of Eduardo Batarda’s works emerges here, precisely in this desire to manifest every single meaning, from the first to the last, with nothing hidden. The result is this schizophrenic visual imagery, which is likely nothing more than Batarda’s perspective on reality. Trying to see through this with our contemporary, rational, objective lens becomes futile; searching for that coveted normality within these "moments" would really be nothing short of crazy.

For these reasons, the work of the two curators, João Mourão and Luís Silva, was absolutely remarkable. They deliberately de-hierarchise their own voice (as we can also read in the conversation with the artist in the catalogue), taking a step back, leaving the door open to the multiple narratives imposed by Batarda's works. Words like "sense" and "reason" seem to crumble with the works in this exhibition, as well as with the faith placed in the scientific objectivity that we have recently grown used to see.

When thinking about it, the complex reality depicted by Batarda convinces me that he is the man dreamed of and sung about by Ivan Graziani. He would be the one who sees "the fire on the hill" while all the others see nothing more than "the headlights of the tractors threshing the field."[3]

Fundação Arpad Szenes - Vieira da Silva

Enzo Di Marino [Vincenzo Di Marino] is an italian curator based in Lisbon. He obtained his MFA in Curatorial Studies at Naba in Milan. In 2018 he co-founded the curatorial research project Bite The Saurus based in Naples. In the last few years he worked with Umberto Di Marino gallery, Naples; Prada Foundation, Milan and Madre Museum, Naples.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro

Notes:

[1] Tanino Liberatore, Ranx. Re/incarnazioni, 2018, Comicon Edizioni, Naples.

[2] Andrea Pazienza, Tutto Zanardi, 2018, Cocoino Press, Rome.

[3] Ivan Graziani, Fuoco sulla collina, 1979, album: Agnese dolce Agnese.