Odete: Excuse me, miss, their history was always a matter of technique

When it comes to Tarot, I have a few favourites. Cards that keep reappearing over the years as themes to keep in mind. I’m still resistant to some, others I’ve adopted very early on. Death is one of those cards I love. One of the most misunderstood things about this card is that it rarely indicates physical death when it appears in a spread; it suggests sudden and irrevocable transformation in one’s life. Death is coming to you in some form, pressing you to mourn that part of yourself that no longer serves you. Often this abrupt change will be subconscious, but if you hold Death’s flag (note that artist and occultist Pamela Colman Smith drew the messenger of Death in the Death card holding a hopeful flag instead of the traditional scythe) your eyes will be wide open to the permanent deaths and rebirths one’s subject to throughout life on this planet—yours and others’. It invites you to welcome them.

Odete and I have read each other’s Tarot a few times. While I’m loyal to the classical Rider-Waite-Smith deck, she’s been using the Thoth Tarot deck, as beautiful as it is powerful. These two decks were published around the same time at the beginning of the twentieth century, and both reflect the teachings of two (and arguably opposing) celebrated academic occultists of the same secret mystic order, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. They were illustrated by two female artists, Pamela Colman Smith, mentioned above—light, decorative, mundane, true to the British Arts and Crafts movement—and Lady Frieda Harris—Deco, occult, sensually austere, intelligent. If I had to attribute a Tarot card to Odete, I would go for a mix of The Magician and Death—one who possesses the tools and craft to master transformation. Much like Odete’s multi-disciplinary work, a Thoth Tarot reading is one that lays shadows bare. And shadow work is not for everyone.

When I speak of tools, I mean she really has them. A gifted composer and producer alongside her visual and performative work and writing, the scope of Odete’s interests and skills is wide and keeps adding.

After releasing three mixtapes and one album, staging a remake of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake for Festival Dias da Dança, and composing the scores for four films and three staged pieces, she was the first awardee of the RExFORM prize for performing arts, which will result in the performance piece Revelations and Muddy Becomings, to premiere this year at MAAT. In the summer of 2020, she opened her first solo exhibition at Bardo, curated by Diana Policarpo—or maybe “second first”, for I remember her solo performance/exhibition Anita Escorre Branco at Rua das Gaivotas 6, in 2019. It was at Bardo that she showed for the first time the film now presented here. The exhibition was titled MTF PRIESTESS CUTTING THE BONE TO REVEAL ITS LIE, generously allowing you to enter it with a detailed image already printed in your mind. You’ve been invited to witness the proceedings of an act of dissection. But unlike the expository methods of Western modern science preoccupied with “truth”, the Priestess in Odete’s show is on to reveal us a lie. What lie? Well, the makings of history, of archaeology, of time. The violences and erasures established by the truth-making systems of colonial cispatriarchy. The lives and legacies of those excluded from truth—transgender, non-binary, intersex peoples. That’s why you must start by cutting the bone. Bone, skeleton, out of which contemporary archaeology often reconstitutes bodies. The bone is too opaque a document, a lie really, and Odete urges us to look beyond (and below) it. I think in part this is what she calls the exercise (or discipline) of Paranoid Archaeology. We must look everywhere for traces of queer ancestrality—burnt, drowned, incarcerated, dissident experiences of gender, still living in documented trial accusations, discarded archaeological findings, cracks in medical reports, and forgotten myths. We must queer the disciplines of history, archaeology, and biology if we are to learn from the traces that have survived us to this day—if only to honour them. Paranoia as well as hysteria are psychosomatic symptoms invented by modernity often used to pathologise marginalised bodies, those deemed unable to perceive or integrate true rational thought. To reclaim “paranoia” as a method with which to study and look at archaeology is to reinscribe agency to those bodies over truth-making systems of exclusion. NÓS NÃO SOMOS DO FUTURO NÓS SOMOS DO PASSADO, Odete writes.

Entering the exhibition, you were lured by colourful drawings of magical chimeras, scraps of wall text of ancient transcriptions mingled with biographical fiction. Detailed miscellaneous illustrations —hand-drawn and digital—formed a layered map of revelations that made it seem alive and in perpetual expansion. Nothing about that show was still. Its figures moved and transformed, ascended, diluted, materialised, and changed shape. Next to the window laid a selection of books, inviting you to stay awhile among that guild of powerful sorceresses, Sanrio dolls, and archaeological scriptures. To read to them or read with them: Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie; books on magic and witchcraft by Doreen Valiente and Scott Cunningham; Susan Stryker’s Transgender History; the autobiography of Catalina de Erauso, among others.

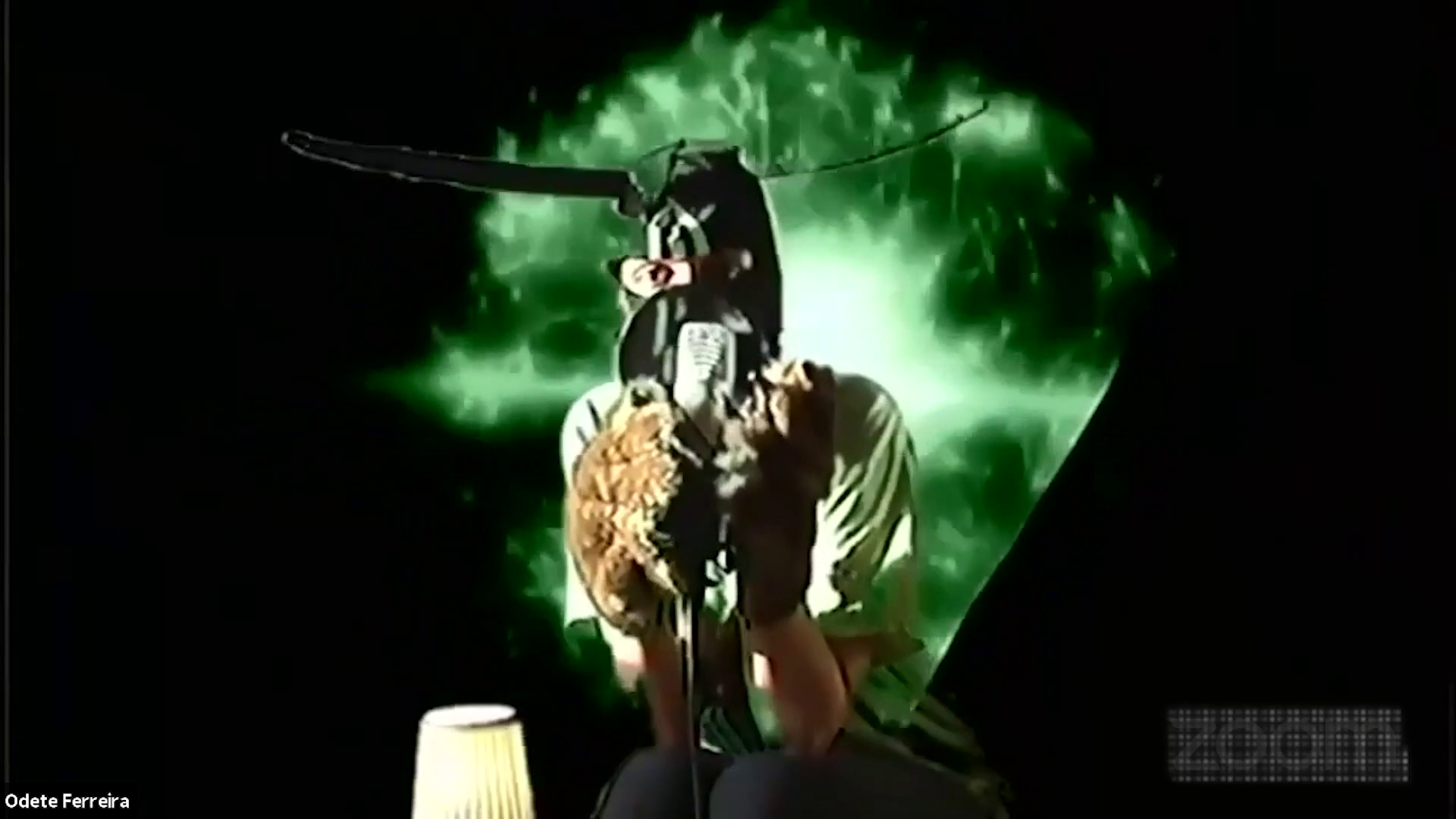

On one corner of the small room, standing on a tripod, a looped video on a large TV. In it, dressed in a hood of long-horns and holding a microphone with large fluffy-paws, Odete (?) spoke gently, almost ASMR-like. Behind her hovered many of the drawings and illustrations in the show, displayed in a dark, isolated space. A lantern guided us through these images, as if in an archaeological site. Something both very markedly present and fragile struck me about these drawings, unframed, stacked in commonality against the gallery’s white walls. They added to something I had observed previously in Odete’s work, a form of radical material precarity. Many of the objects Odete creates seem unbothered with sturdiness or durability; rather, they are generously daily-life-sized. Crafted. They maintain a feeling of assembled alchemical matter, like a country-side sorceress would do in their workshop. After laborious harvest, pick, and brew from what’s around, a potion or charm is created. Have you ever looked at charms? They’re a messy compound of parts—animal secretions, plant roots, torn fabric, dried fungi, a person’s most cherished belonging. They are crafted. And they really work. The Death card for you.