Near Fields: Tecnologia enquanto Paisagem

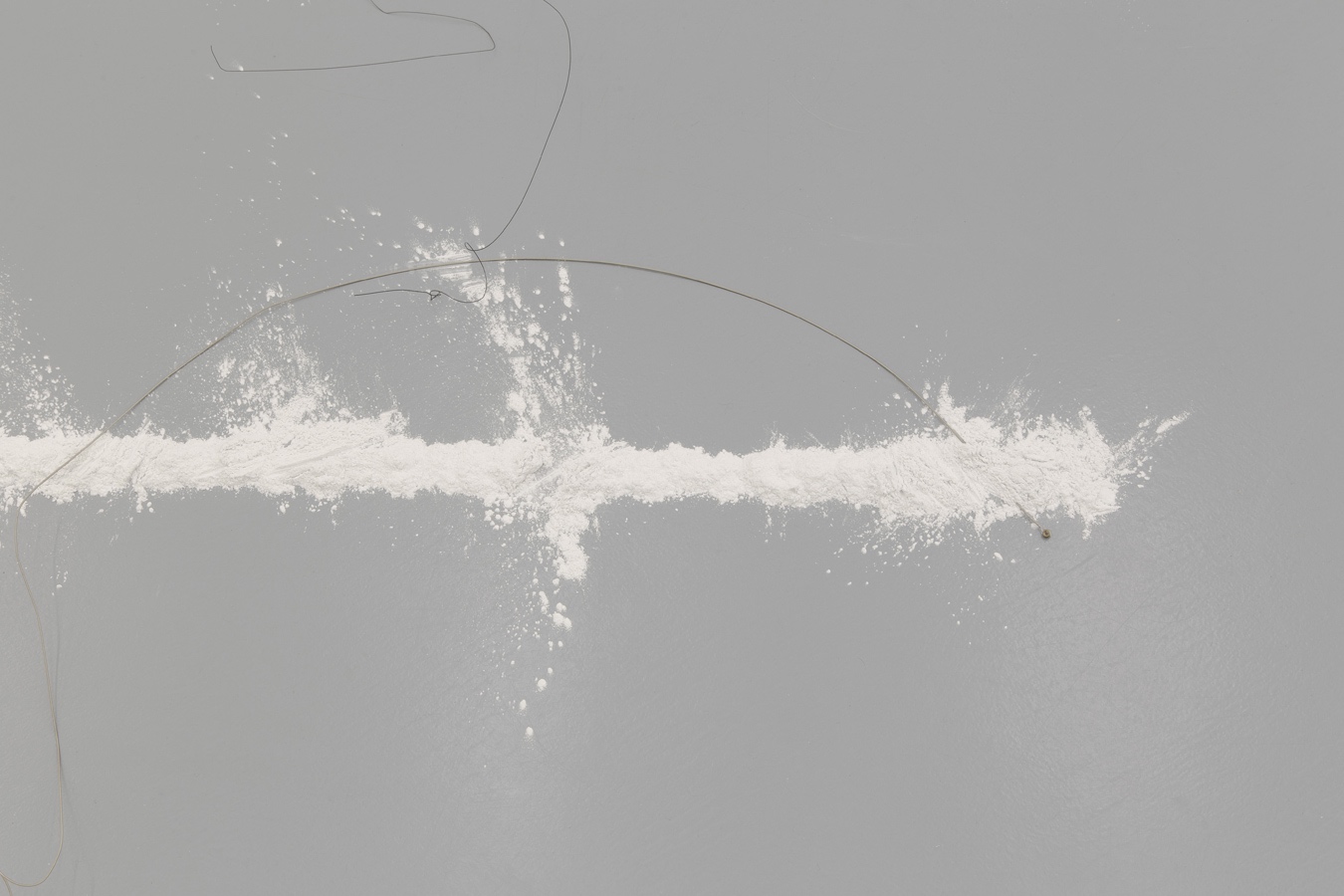

João Paulo Feliciano, White Dust /Rusted Strings, 1992 (detalhe) © João Paulo Feliciano. Fundação Leal Rios. Fotografia: João Biscainho.

Na sua introdução a Collecting the New: Museums and Contemporary Art, o teórico Bruce Altshuler nota que “a colecção e a preservação de objectos tem sido tradicionalmente identificada como uma, senão a principal, função do museu, mas a discussão no seio dos museus e da arte contemporânea tem-se focado sobretudo nas questões de display e exposição”.

As colecções de outrora tornam-se as exposições do presente, uma tendência confirmada pelos principais museus europeus e americanos. Esta tendência tem-se feito notar especialmente em colecções privadas que não pretendem ser “completas” nem manifestam um desejo de cumprir uma função oficial. Pelo contrário, a sua orientação para uma abordagem curatorial define a colecção como um repositório a partir do qual novos displays se apresentam, atomizando e redefinindo o inventário de forma constante. Uma exposição pode ser entendida como um mapeamento parcial da colecção, um território cuja extensão nunca é totalmente conhecida.

A exposição Near Fields na Fundação Leal Rios (FLR) recorre a obras da colecção que abordam a associação entre tecnologia e arte contemporânea, oferecendo ao mesmo tempo um notável exemplo da transformação estrutural de que o sector da arte institucional actualmente é testemunha.

A fundação privada sedeada em Lisboa abriu as suas portas em 2012, embora os irmãos Miguel e Manuel Leal Rios tenham começado a coleccionar nos primeiros anos do novo milénio. O curador e coleccionador Miguel Rios sublinha a importância do modelo expositivo quando descreve os critérios para a colecção como uma tentativa de “identificar e compreender a prática artística da “instalação”… [de modo a] evidenciar… [as suas] contribuições… [para]… um debate contemporâneo sobre a “espacialidade” da obra de arte e a sua relação com os processos de organização e ocupação no espaço expositivo”. [1]

De facto, tal como foi já afirmado, a instalação ao passar da marginalidade para a ubiquidade teve como resultado uma redefinição determinante da apresentação da arte, desde artefactos individuais a um campo expandido e transversal, e a alteração simultânea do papel dos seus produtores: o artista, o curador e o público.

A primeira impressão visual da exposição confirma a estética de display introduzida na fundação. A abordagem é minimal e contida, evitando uma revelação integral. As geometrias espaciais são cuidadosamente respeitadas, enquanto linhas de visão são claramente desenhadas, permitindo que as obras circulem e provoquem ressonâncias dentro dos limites do espaço, o white cube formal. A sinalética de exposição está totalmente ausente. Em vez disso é oferecido um simples mapa, deixando apenas um espaço livre e imaculado, cuja brancura é acentuada pela fluorescência uniforme da iluminação artificial. Curar é, segundo a influente escritora e produtora de exposições Mary Jane Jacob, “entrar numa relação em que se cuida” dos trabalhos e uma demonstração física da afinidade entre conceito, display e espaço.

Em Near Fields, tal como noutras exposições na FLR, a orientação estética do display do coleccionador Miguel Leal Rios e do seu co-curador João Biscainho parece estar em harmonia com as ideias do artista e escritor Rémy Zaugg, cujo livro seminal, The Art Museum of My Dreams, apresenta um espaço ideal. Zaugg começa com uma descrição das paredes:

Todas as paredes do lugar são lisas, verticais e brancas… nenhuma delas permanece estranha à exposição da obra e ao observador. Claras, precisas e impecáveis, nítidas e indiferentes, as paredes lisas, verticais e brancas mantêm-se à distância, mantêm a sua distância. Não colidem com a expressão do trabalho, não competem com este, não o alienam.

A curadoria funciona como uma coreografia subtil que dispõe as peças pelo espaço, ao mesmo tempo que conduz os jogadores, ou visitantes, de um modo subtil. A exposição actua como um espaço programado, um termo desenvolvido pelo teórico Norman M. Klein para designar espaços cuidadosamente desenhados e controlados que conciliam significado cultural com display numa busca de uma atmosfera, algo que não acontece por acaso mas que resulta de uma minuciosa construção.

O título da exposição, Near Fields, é um conceito apropriado da física e descreve o comportamento de diferentes ondas electromagnéticas que emanam de uma fonte, tal como uma coluna, uma antena ou, para usar um exemplo mais recente, um aparelho como um smartphone. Quando aplicado ao domínio do som, o termo é utilizado para distinguir a diferença de comportamento de ondas de som próximas da fonte (onde “circulam e se propagam”) daquelas que estão longe (e que só “propagam”), uma área designada por “Far Field”.

Na exposição homónima, o título serve de instrução, fio condutor curatorial e metáfora. Ao utilizar uma linguagem científica relativamente obscura que acaba por estar bastante presente no nosso quotidiano, os curadores sugerem uma complexidade estratificada da arte contemporânea que, todavia, pode resultar num desarmante acto de percepção. Por outras palavras, a complexidade é mais eficiente quando é simples.

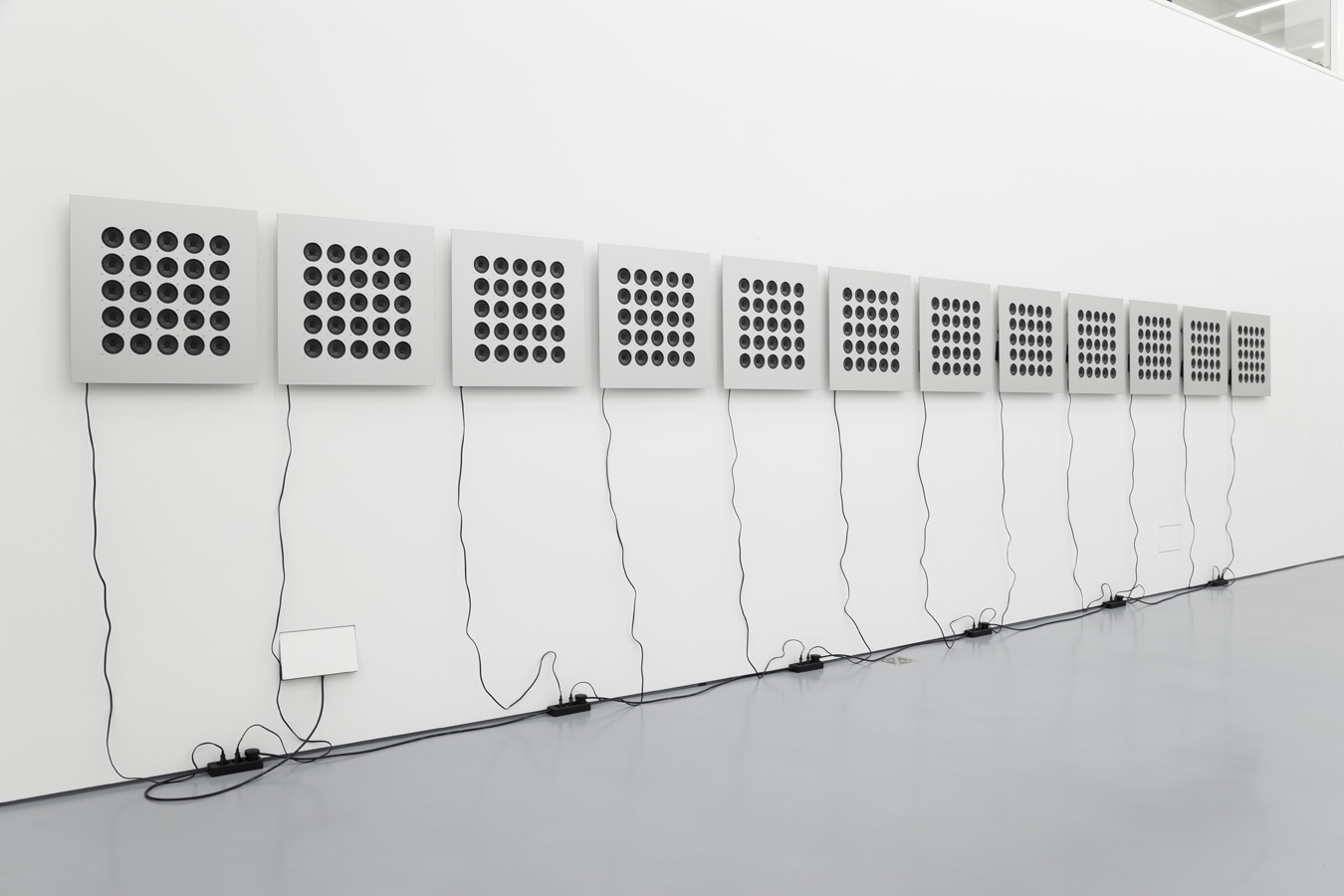

Apesar de o som emanar de várias obras e de atravessar a exposição, Octave (2015), de Tristan Perich, é a única peça a ser identificada como um trabalho de som. 300 colunas de 1-bit encontram-se distribuídas por 12 painéis de alumínio que exploram as frequências microtonais de uma oitava, que se podem ouvir ao percorrer o comprimento total da peça a diferentes velocidades. Machine Drawing (2017) de Perich, 2017-05-17 9:00AM, 2017 é a transcrição mecânica do código feita por uma caneta sobre a parede branca, que tem lugar ao longo da duração da exposição. O resultado não é uma paisagem nem um mapa, mas uma rede densamente estratificada de linhas intrincadas que literalmente inscrevem a sua própria presença no tecido do espaço.

“Eu não vejo a tecnologia como tecnologia”, afirma o artista e compositor Alvin Lucier, “Vejo-a como paisagem”. [8] Paisagem, num sentido lato, é então o lugar no qual toda a percepção cultural, independentemente do grau de interferência humana, acontece. Actualmente, quando dificilmente alguma actividade humana permanece intocada pelo progresso tecnológico, é evidente que a relação entre arte e tecnologia merece também uma análise cuidada.

Esta preocupação não se limita ao tempo actual e os exemplos abundam nas práticas dos Futuristas e Dadaístas na Europa do início do século XX e nos anos 60 nos projectos de investigação revolucionários da E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) nos EUA. Entre estas experiências, o som ocupa uma posição central, assim como acontece na Documenta 14 (2017) de Adam Szymczyk em Atenas e Kassel, onde são apresentadas pesquisas feitas nas vanguardas sónicas desde o século XX. A Documenta 14 mostra um grande número de peças de som e representações de notação musical. De acordo com o crítico Sam Thorne, uma partitura actua como um dispositivo de notação “que flui entre linguagem e corpo”.

Também em Near Fields são utilizadas partituras e mapas espaciais enquanto representações visuais do próprio som. Os desenhos de Jorinde Voigt, Stochastic Storms I + II (2008-10), fazem referência às composições de Iannis Xenakis, um compositor avant-garde conhecido pela sua notação musical altamente visual, enquanto que a instalação de João Paulo Feliciano White Dust/Rusted Strings (1992) - linhas de pó de talco branco misturadas com cordas de guitarra usadas - remete para os excessos da cultura da música rock, fazendo ao mesmo tempo referências à arte minimal e à land art. Os trabalhos de ambos os artistas apresentam paisagens metafóricas cuja performance sónica foi adiada. Um terceiro trabalho que lhes está próximo, Ramita Partita (2016) de Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, conta com dois tripés motorizados cada um suportando um ramo de ameixeira num espelho que gira lentamente. As suas esculturas abordam o binómio natureza/cultura, afirmando pelo contrário a necessidade de uma porosidade entre espaços, dimensões e posições. O filósofo Michel Foucault defende “um espaço que não seja o da filosofia, nem o da literatura ou da arte, mas um espaço da experiência. Estamos numa época em que a experiência […] e… o pensamento… se desenvolvem com uma riqueza extraordinária, tanto na unificação e dispersão que demolem as fronteiras e as áreas que eram outrora bem definidas”.

O jogo espacial da distância criado pela tecnologia - aqui e ali, perto e longe - invade a exposição e manifesta-se especialmente no filme de Anthony McCall Landscape for White Squares (1972) e na pintura Messier 5 (NGC 5904) (2009-10) de Rui Toscano. O filme experimental de McCall mostra uma performance ao vivo gravada in situ e que explora a relação entre sistemas, corpos e espaço. A obra procura “prolongar o tempo de modo a adiar a conclusão de um trabalho para que o público tenha de interrogar a peça a partir do seu interior” - “permutações não se repetem”. O trabalho de Toscano, no seu interesse por paisagens tecnológicas, dá ao espectador um vislumbre do nascimento do nosso universo que começou como uma singularidade, uma zona de densidade infinita. A pintura explora o chamado Efeito Doppler, utilizado para explicar as cores de estrelas binárias à medida que ambas se movem aproximando-se e afastando-se da terra. O seu trabalho lembra-nos quão do nosso modelo ocidental de percepção está enraizado numa cenografia de objecto e sujeito já instituída. Segundo o filósofo Bruno Latour, apreendemos o que se passa à nossa volta através de imagens que são elas próprias o resultado de certas assunções perceptuais em vez de experiências directas.

Nesse sentido, podemos considerar as pinturas de Scott Short como uma forma de contornar esta viragem pictórica, substituindo-a por uma pura reprodução mecânica. Untitled (green Negative) (2010) utiliza tecnologia misteriosa sob a forma de uma fotocopiadora para fazer fotocópias repetidas de cartolinas coloridas, permitindo à máquina tomar controlo antes de projectar e pintar a imagem final. Aqui a reprodução funciona como um sistema hermético interrompido pela mão humana.

O elemento final na coreografia da exposição é o vídeo de Pedro Diniz Reis, Zaubergesang zur Krankenheilung (Songs of Magic to Heal Sickness) (2013), um monitor antigo que mostra ruído de vídeo analógico oriundo de uma cassete Betacam gravada com sinal vermelho e que foi manipulada de modo a mostrar a progressiva deterioração da imagem. A acompanhar o vídeo uma canção de um ritual oculto interpretada na ilha de Sumatra em 1905. Tanto imagem como som estão combinados com precisão numa localização específica, no entanto permanecem inacessíveis e os seus significados originais não podem ser apreendidos.

Ao comprimir a experiência espaciotemporal, a tecnologia oferece-nos uma relação profundamente alterada com o nosso ambiente. As percepções e certezas de inspiração pictórica do passado estão a ser ultrapassadas por novas formas de olhar. É, no entanto, através da arte que conseguimos ter uma relação crítica com esta nova paisagem. A arte não serve para simplificar ou tornar plano aquilo que é difícil de compreender, mas sim insistir que a complexidade se mantenha no centro do esforço para compreender, explorar e celebrar quem somos.

É apenas devido à nossa capacidade de “ver o mundo através de uma lente dupla” que podemos conceber tanto o mundo natural como a cultura como diferentes daquilo que são na realidade. Porque conseguimos distinguir entre o mundo real e uma “realidade” imaginada ou ficcional, a mudança e a inovação estão dentro do real da possibilidade humana. Independentemente de tal mudança significar progresso ou retrocesso, a nossa capacidade de oscilar entre a não-ficção e a ficção é fundamental para a imaginação de outros mundos, em ser-se criativo, [ou] em apresentar diferentes modelos de sociedade. [14]

Near Fields funciona como uma janela para a colecção FLR, oferencedo um olhar parcial sobre o seu inventário, mas principalmente sobre a sua identidade, algo que todos os corpos de trabalho importantes deveriam ter. O que é revelado não é uma unidade estilística ou discursiva, mas em vez disso uma entidade mutável enquadrada pelas preocupações espaciotemporais.

Afinal, todas as colecções modernas e contemporâneas possuem trabalhos de um passado recente ou mais distante, mas é o seu grau de abertura ao risco e à experimentação que revela os seus planos no presente e no futuro. Este posicionamento singular é confirmado por todos os aspectos das novas acções de uma colecção: a sua estratégia de aquisição, as exposições, publicações, a comunicação da sua identidade. Em suma, a colecção não é em primeiro lugar uma coisa material, mas um acontecimento. A definição científica de Near Fields oferece então uma analogia excêntrica ao actual papel de uma colecção em que, à semelhança das ondas electromagnéticas produzidas por uma fonte, as suas acções devem ‘circular e propagar-se’.

Nicolas de Oliveira e Nicola Oxley

São escritores e curadores que trabalham e vivem em Londres. São co-autores de importantes obras sobre instalações artísticas, bem como de monografias individuais de autores. Co-dirigem um espaço de projectos experimental, a SE8 Gallery, e uma editora The Mulberry Press que publica livros de artista e edições em vinil. De Oliveira é também director da fundação Art Institutions of the 21st Century, um grupo de reflexão internacional que desenvolve e apresenta pesquisas através de simpósios e relatórios publicados sobre políticas institucionais.

tradução do inglês por Gonçalo Gama Pinto

Original em inglês

Near Fields: Technology as Landscape

In his introduction to Collecting the New: Museums and Contemporary Art theorist Bruce Altshuler comments that ‘the collecting and preserving of objects has traditionally been marked as a – if not the – central function of the museum, but discussion of museums and contemporary art has focused almost entirely on issues of display and exhibition.’ [1]

The collections of yesteryear give way to the exhibitions of the present, a tendency borne out in major museums throughout Europe and the Americas. This trend has been especially apparent in private collections that do not pretend to be ‘complete’ or harbour a desire to fulfill an authoritative function; rather their inclination towards a curatorial approach defines the collection as a repository from which new displays are made, constantly atomizing and redefining the inventory. An exhibition can be seen as a partial mapping of the collection, a territory whose full extent is never known.

The exhibition ‘Near Fields’ at Fundação Leal Rios (FLR) deploys works from the collection, which address the affiliation between technology and contemporary art, whilst offering a salient instance of the structural transformation currently being witnessed in the art institutional sector.

The Lisbon-based private foundation opened its doors in 2012, though the collecting activity of brothers Miguel and Manuel Leal Rios began in the early years of the new millennium. The collector and curator Miguel Rios underlines the importance of the exhibition mode when describing the criteria for the collection as an attempt to ‘identify and understand the artistic practice of "installation”…[in order to] emphasize…[its] contributions…[to]…a contemporary debate on "spatiality" of the artwork and its relationship with the processes of organization and occupation in the exhibition space. [2]

Indeed, as has been argued elsewhere the move of installation art from marginality to ubiquity has resulted in a crucial redefinition of the presentation of art, from individual artifacts to an expanded, unified field, and to the concomitant shift in the role of its producers – the artist, the curator and the audience. [3]

The first, visual impression of the exhibition confirms the display aesthetic pioneered at the foundation. The approach is minimal and restrained, holding back from the full disclosure of a prescriptive stance. Spatial geometries are carefully observed, while lines of sight are clearly drawn, allowing the works to circulate and resonate within the confines of the container, the formal white cube. Exhibition signage is entirely absent – a simple map is offered instead [4], leaving only a pristine, unencumbered space, its whiteness emphasized by the flat fluorescence of the artificial lighting. To curate is, according to the influential exhibition maker and writer Mary Jane Jacob, ‘to enter into a caring relationship’ [5] with the works themselves, and a physical demonstration of the affinity between concept, display and space.

In Near Fields, as in the other exhibitions at FLR, the aesthetic display stance of collector Miguel Leal Rios, and his co-curator João Biscainho appears to chime with the ideas of the artist and writer Rémy Zaugg whose seminal book, The Art Museum of My Dreams, lays out an ideal space. Zaugg begins with a description of the walls:

All the walls of the place are flat, vertical and white…none of them remain foreign to the exposure of the work and the beholder. Clear, precise and impeccable, obvious and impassive, the flat, vertical and white walls remain at a distance, they keep their distance. They do not enter into a collusion with the expression of the work, they do not compete with it, they do not alienate it. [6]

Curating functions as a subtle choreography that arranges the pieces throughout the space, whilst ushering the players – or visitors – about with subtle encouragement. The exhibition acts as scripted space, a term developed by theorist Norman M.Klein to denote carefully designed and controlled spaces [7] that reconcile cultural meaning with display in the pursuit of atmosphere, something not arrived at by happenstance, but as the result of meticulous construction.

The title of the exhibition Near Fields is borrowed from physics and describes the behavior of different electromagnetic waves emanating from a source, such as a loudspeaker, an antenna, or, latterly, a device such as a smartphone. When applied to the realm of sound, the term is used to distinguish the difference in behavior of soundwaves close to the source (where they ‘circulate and propagate’), and those in the distance (where they only ‘propagate’), an area termed ‘Far Field’.

In the eponymous exhibition the title serves as part instruction, curatorial leitmotif, and metaphor. In borrowing a relatively obscure scientific language that turns out to have extensive application in our everyday, the curators point towards the layered complexity of contemporary art that nevertheless can result in a disarmingly direct act of perception. Complexity, in other words is most effective when it is simple.

Though sound emanates from a number of works and percolates through the exhibition Tristan Perich’s Octave (2015) is alone in being identified as a sonic work. It distributes 300 1-bit speakers across 12 aluminium panels to explore the microtonal frequencies in an octave, experienced by walking past the length of the work at varying speeds. Perich’s Machine Drawing (2017) 2017-05-17 9:00AM, 2017 is the mechanical transcription of code by a pen on a white wall, undertaken throughout the duration of the exhibition. Neither a landscape nor a map, the result is a densely layered web of intricate lines that quite literally inscribes its own presence on the fabric of the space.

‘I don’t think of technology as technology’, argues the artist and composer Alvin Lucier, ‘I think of it as landscape’ [8]. Landscape, in an expanded sense, is then the place in which all cultural perception - regardless of the degree of human interference – takes hold. Today, when hardly a human activity remains untouched by the march of technological advancement, it is evident that the relationship between art and technology must also bear significant scrutiny.

This preoccupation is not confined to the present day, and examples abound throughout the practices of the Futurists and Dadaists in Europe in the early 20th century and, by the 1960s in the groundbreaking research projects of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) in the United States. Among these experiments sound occupies a central position, as it does in Adam Szymczyk’s Documenta 14 (2017) in Athens and Kassel, featuring investigations into sonic avantgardes from the 20th century; accordingly, D14 shows a large number of soundworks and depictions of musical notation. According to critic Sam Thorne, a score acts as a notational device ‘that trans-acts between language and body.’ [9]

The use of scores and spatial maps as visual depictions of actual sound also recurs in Near Fields. Jorinde Voigt’s drawings Stochastic Storms I + II (2008-10) reference the scores of Iannis Xenakis [10], an avant-garde composer who was renowned for highly visual musical notation, while João Paulo Feliciano’s floor-based installation White Dust/Rusted Strings (1992) – lines of white talcum powder and embedded, used guitar Strings - refer to the excesses of rock music culture whilst referencing minimal and land art. Both artists’ works present metaphorical landscapes whose sonic performance has been deferred. A third work placed nearby, Daniel Steegmann Mangrané’s Ramita Partita (2016), features two motorised tripods each supporting a plum tree branch on a slowly rotating mirror; his sculptures address the distinction between the binary opposition of nature/culture, affirming instead the need for a leaching or porosity between spaces, dimensions and positions. Philosopher Michel Foucault argues for ‘a space that is not that of philosophy, not of literature, nor of art, but that of experience. We are now in a time when experience […] and… thought… are developing with an extraordinary richness, in both a unity and a dispersion that wipe out the boundaries and provinces that were once well established.’ [11]

The spatial game of distance brought about by technology – here and there, near and far – pervades the exhibition and is especially patent in the film of Anthony McCall Landscape for White Squares (1972) and the painting Messier 5 (NGC 5904) (2009-10) by Rui Toscano. McCall’s experimental film depicts a live performance recorded on site exploring the relationship between systems, bodies and space. The complete artwork seeks to ‘extend time to defer the completion of a work so that the audience had to interrogate the piece from within’ – ‘permutations don’t repeat themselves.’ [12] Toscano’s work, underscored by his interest in technological landscapes gives the viewer a glimpse of the birth of our universe, which began as a singularity, a zone of infinite density. The painting explores the so-called ‘Doppler effect’, used to explain the colours of binary stars as they move both towards and away from the earth. His work is a reminder of how much our western model of perception is rooted in a received scenography of object and subject. According to philosopher Bruno Latour we apprehend our surroundings by images, which are themselves the result of certain perceptual assumptions, rather than by direct experience. [13]

With the above in mind, one might consider Scott Short’s paintings as a way of circumventing such a pictorial turn, by replacing it with pure mechanical reproduction. Untitled (green Negative) (2010) uses arcane technology in the form of the Xerox copier, to make repeated photocopies of single-coloured construction paper, allowing the machine to take over, before projecting and painting the final image. Here, reproduction functions as a hermetic system interrupted by the human hand.

The final element in the choreography of the exhibition is Pedro Diniz Reis’s video Zaubergesang zur Krankenheiligung (Songs of Magic to Heal Sickness) (2013), a single vintage monitor showing analog video noise derived from a Betacam tape that had been recorded with red signal and manipulated to display the progressive degradation of the image. Accompanying the video is a song from an occult ritual performed on the island of Sumatra in 1905. Both image and sound are precisely embedded in a specific location, yet they remain inaccessible, and their original meanings cannot be retrieved.

By compressing spatio-temporal experience technology offers us a extensively altered relationship to our environment. The pictorially-inflected perceptions and certainties of the past are being superseded by new ways of seeing. It is however through art, that we come to have a critical relationship with this new landscape. Art does not serve to flatten, or to make plain what is hard to grasp, but rather to insist that complexity remain at the heart of the endeavor to understand, explore and memorialize who we are.

It is only because of our ability to “see the world through a double lens” that we can conceive of both the natural world and culture as being different than what they are in reality. Because we can distinguish between the real world and an imagined, or fictional “reality”, change and innovation are within the real of human possibility. Regardless of whether such change means progression or regression, our ability to oscillate between non-fiction and fiction is crucial in imagining other worlds, in being creative, [or] in presenting different models of society. [14]

Near Fields functions as a window into the FLR collection, offering a partial glimpse of its inventory, but more importantly, into its identity, something which every significant body of work ought to have. What is revealed is not a stylistic or discoursive unit, but instead, a mutable entity framed by spatio-temporal concerns.

After all, every modern and contemporary collection holds works from the recent or more distant past, but it is its degree of openness to risk and experimentation that reveals its designs on the present and the future; this distinct positioning is borne out in every aspect of a collection’s new actions: its acquisition strategy, its exhibitions, its publications, the communication of its identity. In short, the collection is not primarily a material thing, but an event. The scientific definition of Near Fields then provides an eccentric analogy to the role of a collection today, in that – like the electromagnetic waves produced by a source - its actions ought to both ‘circulate and propagate’.

[1] Bruce Altshuler, Collecting the New: Museums and Contemporary Art, Princeton University Press, 2005, p.1.

[2] Miguel Leal Rios, Interview, BMWArt Guide, https://www.bmw-art-guide.com/idx/preview/interview-with-miguel-leal-rios

[3] Nicolas de Oliveira, Nicola Oxley et al, Empire of the Senses: Installation art in the New Millennium, Thames & Hudson, London and NewYork, 2003, op.cit.

[4] The map forms part of a booklet with a critical essay by the co-curator João Biscainho.

[5] Mary Jane Jacob, in The Ways of folding Space and flying: Moon Kyungwon & Jeon Joonho, Cultureshock Media, London 2015, p.66

[6] Rémy Zaugg, The Art Museum of My Dreams, Sternberg Press, Berlin, 2013.

[7] Norman M. Klein, From the Vatican to Vegas: A History of Special Effects, The New Press, New York andLondon, 2004, op.cit.

[8] Alvin Lucier, quoted in Adam Frank, Feeling, in Experience: Culture, Cognition and the Common Sense, Caroline E.Jones et al (eds), Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST), MIT Press, Camb. Mass, 2015, p.145.

[9] Sam Thorne, Keeping Score, Frieze June-July 2017, p.19.

[10] Xenakis’s Stochastic Music is composed using a technique derived from random mathematical functions.

[11] Michel Foucault, Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, James D. Faubion (ed.), The New Press, New York, 1998,p.174.

[12] Christopher Eamon, Anthony McCall: The Solid Light Films and Related Works, Steidl, San Francisco, 2005, P.13.

[13] Bruno Latour, in Experience: Culture, Cognition and the Common Sense, Caroline E.Jones et al (eds), Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST), MIT Press, Camb. Mass, 2015, p.317.

[14] Pascal Gielen, in Institutional Attitudes: Instituting Art ina Flat World, Antannae/Valiz, Amsterdam, 2013, p.12.