Diana Policarpo: Agência Reverberante

Moving of masses,

Stirred by astro-phenomena,

Directing matter,

Their slave, yet their master,

Still to be.

Effort, research, action,

Thought bearing power, strength,

And courage abundant

To wrestle from the elements

The secret kept.

— Johanna M. Beyer, Three Songs for Clarinet and Voice (de Sticky Melodies, 1934)

Profunda, plena e reverberante, capaz de produzir afectos, carinhosa — seria provavelmente a forma que utilizaríamos para descrever uma voz amigável ou a expressão recíproca que emana do interior e se dirige ao exterior na direção de um outro empático. No cruzamento entre manifestação e agenciamento, a ressonância redireciona o ouvinte do culto moderno da visão no sentido das vozes que circulam por entre corpos e signos.

Partindo destes termos e dos discursos interligados sobre tempo histórico e auscultação, este ensaio aborda a ética da cumplicidade e do envolvimento proposta pela artista visual e sonora, também compositora electro-acústica, nascida em Portugal e sediada em Londres, Diana Policarpo (1986, Lisboa). Caracterizado por uma tentativa de escutar a “pequena voz da história" [1] o ensaio procura desafiar os pressupostos que classificam o afecto como matéria privada ou bilateral e sugere que, pelo contrário, é fundamental contar histórias alternativas sobre a composição e o desenvolvimento capitalista nas práticas sonoras. As obras de Policarpo concebem uma posição de escuta a partir da qual ouvir “os refrões e reverberações através das quais nos agarramos ao mundo e aos outros" [2] e surgem no encontro entre a teoria feminista e as contribuições arquivísticas que se estendem mais além do cânone musical. Embora a prática de Policarpo convoque uma estratégia cinemática que tanto combina abordagens visuais como aurais, defendo que este esquema confunde as possibilidades de representação que na cultura ocidental tem historicamente privilegiado concepções de comunicação visuais e espaciais. Como Brandon LaBelle atentamente escreveu na sua mais recente monografia sobre "Sonic Agency".

"Enquanto movimento vigoroso — de intensidade rítmica e reverberantes, de interrupções vibracionais e volumétricas —, o som opera de modo a desestabilizar e exceder os campos da visibilidade ao relacionar-nos com o invisível, o não representado ou que ainda não é aparente; juntamente com espaços de aparência e as visibilidades legíveis que definem muitas vezes o discurso aberto (...)" [3]

De Descartes a Deleuze, ressonância e auralidade têm sido temas centrais na discussão da razão materializada. Em Compendium Musicae (1618), René Descartes escreve: “A voz humana parece-nos mais agradável porque se ajusta mais directamente às nossas almas. Do mesmo modo, parece que a voz de um amigo próximo é mais agradável do que a voz de um inimigo, devido aos sentimentos de simpatia ou antipatia" [4]. Implícitas ao emaranhado cartesiano de afecto e escuta estão a consciência dialógica e as intensidades efémeras na sensação e no pensamento que ilustram a capacidade de um corpo para ser afectado e afectar.

Tal parece sugerir que afecto e escuta incorporada não são apenas a verdadeira materialidade da percepção auditiva, mas também da relação bilateral da prática ética.

Enquanto que, por um lado, o comentário de Descartes invoca a experiência física, nomeadamente a ressonância, que o Oxford Dictionary of English descreve como o “reforço ou prolongamento de som pelo reflexo de uma superfície ou pela vibração sincrónica de um objecto vizinho”, relembra também as discussões sobre auscultação, termo privilegiado em filosofia, para especular sobre a direccionalidade da escuta. Abordando a primeira, o académico holandês Veit Erlmann observa que “a ressonância é extremamente adequada na dissolução do carácter binário da materialidade das coisas e da imaterialidade dos signos que historicamente preocuparam o discurso feminista." [5] Erlmann continua:

“(…) num contraste marcado à célebre declaração do filósofo de que apenas a “inaudível fundação da verdade” reside no facto de que penso coisas e que este res cogitans é “inteira e verdadeiramente” distinto do corpo e que "pode existir sem ele" ”. Apesar do termo se ter banalizado nas traduções modernas, o termo latino preferido de Descartes é inconsussum (inabalável). Proveniente da raiz - cutere (abanar violentamente)." [6]

Em última análise, ao reler os textos de Descartes sobre música e som e confrontando-os com as célebres Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), em que o filósofo contrapõe visão e escuta como processos desigualmente privilegiados de acesso à realidade, Erlmann afirma que, mesmo em Descartes, este movimento percussivo é um objecto legítimo de conhecimento. Os argumentos de Erlmann partem de uma leitura atenta de inconsussum e dos seus usos na astronomia moderna para concluir que “várias formas cognatas de — cutere penetraram no discurso académico durante a Revolução Científica”. A episteme rítmica implícita ao argumento de Erlmann é também fundamental na compreensão da segunda leitura de Descartes através da auscultação, revelando novos modos de vida através da atenção a actualidades e intensidades. A investigadora em comunicação Lisbeth Lipari, por exemplo, concilia estes dois aspectos ao articular a ‘interescuta’ aqui praticada como declaração ética e retransmissor entre corpo e mente e como política de operação e possibilidade:

"Do mesmo modo que a intersubjectividade descreve a forma como as interacções dialógicas transcendem simples fronteiras entre o eu e o outro, também a interescuta descreve as formas como o diálogo transcende as fronteiras do tempo, do espaço e do indivíduo. A interescuta procura assim descrever como a escuta é em si mesma uma forma de diálogo que reverbera com ecos de tudo o que foi ouvido, pensado, dito e lido. (…) A interescuta dá múltiplos ênfases sobre o inter de interacção, interdependência, interrelação, intersubjectividade, bem como o reconhecimento da sintonia, atenção e alteridade, sempre incorporadas nos nossos processos de comunicação." [7]

Como podemos então, neste cenário, harmonizar as intensidades do som com as fronteiras permeáveis da ressonância que operam como uma força preponderante? A grande maioria dos exemplos canónicos da segunda metade do século XX afastaram o som da sua materialização. John Cage, por exemplo, referiu-se à capacidade da tecnologia de “libertar” sons dos objectos, sem que o som tivesse necessariamente qualquer relação com o contexto aural em que ocorreu inicialmente. [8] Pierre Schaeffer defendeu também uma neutralidade do som, afastando a experiência auditiva da sua apreensão visual, utilizando o termo acusmático para definir a percepção não mediada do som: “Acusmático, adjectivo: relativo a som cuja fonte não é visível." [9]

No entanto, alguns dos seus colaboradores tinham perspectivas divergentes sobre a experiência sónica. Eliane Radigue (1932) estudou com Pierre Schaeffer na década de 1950, tornando-se assistente do colega e criador da musique concrète Pierre Henry nos anos 60. O trabalho de Radigue que, à época, incluía a colagem e manipulação de sons com fitas magnéticas e feedback de microfones, foi recebido de forma hostil por Henry e Schaeffer que a acusaram de se afastar dos ideais do movimento. Próximo da década de 1970, Radigue mudou-se para Nova Iorque onde conheceu os compositores minimalistas e descobriu o sistema modular ARP 2500, o sintetizador que viria a definir a sua estética. Trabalhando em solidão e durante longos períodos de tempo, as suas composições são um lento desabrochar de som, desenvolvidas a partir de uma experiência aberta e profundamente envolvente com a solidão e a meditação budista. [10]

As duas últimas são experiências fundamentais que percorrem o continuum de várias outras figuras femininas do campo emergente da música electrónica. Alice Coltrane (1937-2007), cujo nome espiritual era Turiyasangitananda, foi uma compositora, harpista, pianista e organista que se envolveu profundamente nas experimentações com as músicas indiana, africana e do Médio Oriente, tendo preconizado o termo ‘jazz espiritual’. Em 1965 casou-se com John Coltrane, que faleceu dois anos depois. Turiya educou os seus três filhos (tal como aconteceu com Radigue, que se casou com o artista francês Arman e criou os seus três filhos na zona rural francesa) e embarcou numa carreira a solo influenciada pelo seu percurso espiritual e pelas suas viagens Afrofuturistas. Na costa oposta dos EUA, Maryanne Amacher (1938-2009), que foi aluna de Karlheinz Stockhausen e colaborou com Cage e Merce Cunningham, compôs sons que se prolongavam até ao limite da percepção auditiva, indo ao encontro daquilo a que chamou de “fenómenos psicoacústicos”: um acontecimento corpóreo definido por um mecanismo vibrante dentro da cóclea, órgão do ouvido interno, que dá uma extrema sensibilidade ao aparelho auditivo dos mamíferos e e provoca uma sensação semelhante à de estados alterados de consciência. As perspectivas de Amacher estavam mais próximas das de Stockhausen que não via qualquer diferença entre o seu corpo, as suas composições, a natureza interior dos sons, a sua fonte espacial, a organização do universo e a força que tudo unia: “Todos somos transístores, no sentido literal…" [11]

Estas três figuras tiveram um entendimento significativo sobre agência sonora enquanto fenómenos materializados e de como esta se relaciona com o desenvolvimento geral do domínio do capital no início do nosso século, que foi abordado através de uma oclusão continuada da materialização enquanto processo fundador e que revela as condições estruturais das sociedades capitalistas pós-coloniais. Desde a década de 1970, a teoria feminista tem mostrado a possibilidade de intersectar a dicotomia entre patriarcado, classe e processos de racialização derrubando as obliterações levadas a cabo pela teoria crítica, nomeadamente através da análise de Michel Foucault das técnicas de poder que perpetaram o corpo na época moderna. Silvia Federici, Paul B. Preciado e Denise Ferreira da Silva, entre outra/os, demonstraram como violentos ataques ao corpo durante as primeiras fases do desenvolvimento capitalista, da colonização à expropriação, foram fundamentais para a “acumulação primitiva”.

Mas esta/es autora/es previram também a hipótese de movimentos alternativos e ‘vigorosos’, com base na solidariedade transtemporal, na revisão histórica e no activismo. É fundamental a nossa identificação com figuras vulneráveis, argumentam, com a precariedade dos corpos femininos cujo trabalho quotidiano é muitas vezes não remunerado e com a exclusão histórica da mulher do desenvolvimento do capitalismo (também nos relatos marxistas e pós-estruturalistas) de modo a testar condições através das quais possamos accionar práticas de resgate, resistência e de perscrutação do cânone. Como Brandon LaBelle cuidadosamente observou: “O som ensina-nos a ser fracos e a usar a fraqueza como uma posição de força." [12]

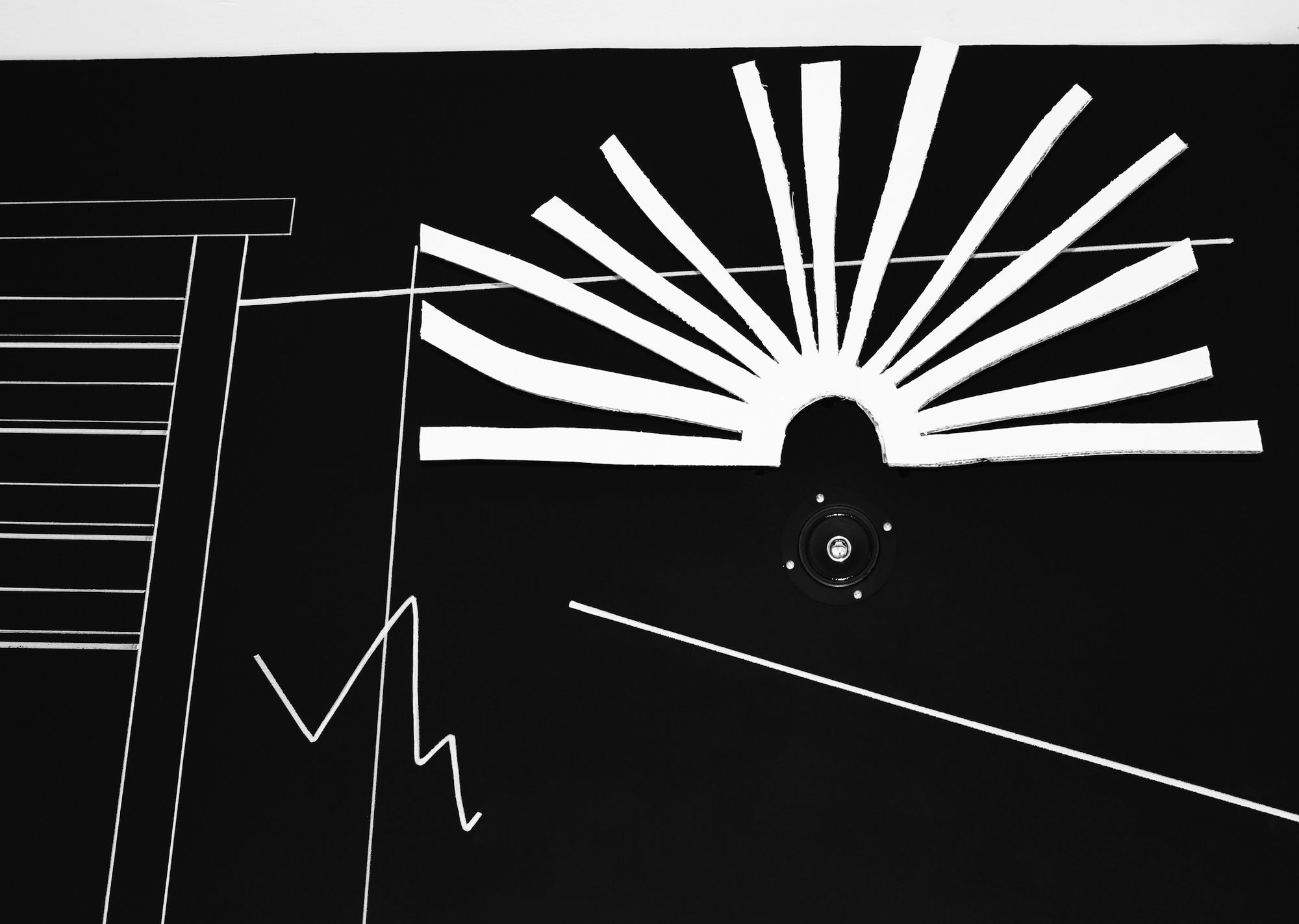

Depois da provocação de Descartes, o som harmonioso de uma voz amiga surge como o resultado de sentimentos escutados de apoio, solidariedade e afinidade, quer sejam recíprocos na expressão ou historicamente contemporâneos. Nos últimos quatro anos, Diana Policarpo tem trabalhado com os arquivos da compositora ultra-modernista germano-americana Johanna M. Beyer (1888-1944), figura pioneira no campo da música orquestral e electrónica. Depois de conhecer as peças da compositora numa compilação sonora de 1977, Policarpo deu início a uma exaustiva investigação de arquivo em Nova Iorque e procurou expandir as suas notas e materiais através de uma série de trabalhos “cuidadosamente compostos e executados, que são gravados e repetidos no espaço da exposição”, observa a artista em correspondência por email. Policarpo começou por interessar-se pela ópera política de Beyer Status Quo / Music for the Spheres (1938), um Gesamtkunstwerk sem concretização e que esteve perdida durante mais de 70 anos. Esta tornou-se a fonte material para a instalação de Policarpo, Sun in Cancer (2016), composta por seis canais áudio e quatro esculturas de som, pautas visuais fundidas em aço e uma envolvente superfície de vidro azul.

Policarpo refere-se às suas composições e obra visual como “anfitriões da investigação”, apresentando as suas instalações não como reproduções ou reinterpretações da obra de Beyer, mas antes como uma narrativa sobre as condições gerais em que o seu trabalho se desenvolveu. Aqui, a artista adopta uma análise precisa dos processos de subjectivação associados à governação capitalista e, como nota o filósofo italiano Maurizio Lazzarato, Policarpo cria um palco para “a relação entre o discursivo e o não-discursivo, o conceptual e o existencial, que não deveria terminar em silêncio (…), mas que deve ser trabalhado, conceptualizado, semiotizado, planeado, narrado, etc., começando a partir do irrepresentável". [13] Em Sun in Cancer (2016) e Dissonant Counterpoint (2017), os sons fantasmagóricos de Beyer são reconstruídos a partir da partitura original e da sua partilha pessoal com o compositor ultra-modernista Henry Cowell e colegas, reverberando num campo sensível — uma ética da cumplicidade — com as contra-vozes da História, o que permite que a expressão afectiva surja como auscultação com o silêncio, o silenciado e o que mal se ouve.

Como Nikita Dhawan pertinentemente argumenta : “Aquele que consegue estar em silêncio encontra-se numa posição de escuta, e aquele que escuta entrega-se aos silêncios dos discursos - aos silêncios esquivos mas também aos silêncios legitimados, aos silêncios que estão sujeitos à nossa vontade e àqueles que comandam a nossa linguagem, o nosso ser" [14]. A maior parte das composições de Beyer permanece preservada unicamente em registos gráficos. Parte de Sun in Cancer (2016), Status Quo/Music of the Spheres foi escrita nos anos que decorreram entre o diagnóstico de uma perturbação nervosa crónica e a sua morte em 1944. E somente em 1977 a peça inacabada foi arranjada e estreada na Califórnia. Dissonant Counterpoint (2017), uma composição electroacústica para nove canais, inclui as seguintes composições de Beyer Total Eclipse (1934), Universal-Local (1934), Two Movements: Three Songs for Soprano and Clarinet (1934-38), e a composição de Policarpo, The Spheres (2017).

Dissonant Counterpoint também torna visível a correspondência amorosa não correspondida com Cowell. Algumas das suas citações citações ressoam nas esculturas sonoras, enquanto excertos da ópera aparecem num ecrã de LEDs em formato de texto contínuo. Nas suas cartas, Cowell surge como uma obsessão e obstáculo, mas sobretudo como a consciência da inevitabilidade à sua referência e do seu próprio acesso à legibilidade no tempo histórico. Como E.C. Feiss observa: “Aquilo que sabemos a partir das histórias revisionistas, actualmente em curso, sobre Beyer (que procuram uma intervenção na narrativa da música modernista) é que ela assumiu um cargo (não remunerado) de assistente de Cowell. Beyer é retirada da penumbra da administração feminina que tantas vezes caracteriza o destino das mulheres antes da invenção da sua história” [15]. Curiosamente, depois do Presidente da Câmara de Leipzig ter visitado a instalação de Policarpo na Kunstverein, foi colocada, em Leipzig, uma placa em homenagem à vida e obra de Beyer, um gesto redentor que reverbera na instalação de Policarpo Visions of Excess (2015), onde a artista junta o texto de George Bataille The Accursed Share: an Essay on General Economy (1946-49) com Caliban and the Witch (2004), de Silvia Federici, uma análise feminista fundamental da história da opressão das mulheres no desenvolvimento capitalista.

Numa prática sónica de comunhão aural, sintonizarmo-nos com o mundo significa chamar a atenção para a relação intrincada entre linguagem e discurso, poder e violência, legibilidade e desigualdade. Partindo da provocação de Susan Sontag “O silêncio é o derradeiro gesto transcendente do artista" [16], a auscultação é fundamental a qualquer posição auditiva, que na prática de Policarpo é apresentada em si e sobre si. A esta questão — a relação entre a expressão sonora, o corpo e o afecto como meios de comunicação com o mundo —, as obras de Policarpo propõem uma ética complexa do pensamento sónico e da materialidade. Anteriormente castrada pelo discurso amanhecente do Iluminismo, a união entre mente e ouvido irradia a impossibilidade de conter a singularidade. Intimamente relacionadas, ressonância e auscultação são os bastiões da sua aliança.

Sofia Lemos é curadora de artes visuais sediada em Berlim e no Porto. É Curadora-Assistente da Galeria Municipal do Porto e co-fundadora (com Alexandra Balona) de PROSPECTIONS for Art, Education e Knowledge Production, uma assembleia peripatética em artes visuais e performativas. Recentemente foi investigadora na Haus der Kulturen der Welt em Berlim e coordenadora do programa público da Contour Biennale 8. Entre 2015 e 2017 formou parte do Grupo de Investigação Curatorial Synapse da HKW, Berlim. Os seus textos têm sido publicados em vdrome, art-agenda, …ment, e Archis/Volume, entre outros.

Tradução do inglês por Gonçalo Gama Pinto

Imagens/Images: Diana Policarpo: Visions of Excess (2015). Cortesia da Artista. Courtesy the artist; Sun in Cancer (2016). Foto/Photo: Lucie Marsmann; Dissonant Counterpoint (2017). Foto/Photo: Casper Saenger.

Diana Policarpo: Sounding Agency

By Sofia Lemos

Moving of masses,

Stirred by astro-phenomena,

Directing matter,

Their slave, yet their master,

Still to be.

Effort, research, action,

Thought bearing power, strength,

And courage abundant

To wrestle from the elements

The secret kept.

— Johanna M. Beyer, Three Songs for Clarinet and Voice (from Sticky Melodies, 1934)

Deep, full and reverberating; capable of moving affects, caring—this is how one would likely address a friendly voice, or a two-way expression that emerges from within and moves outwards towards an empathic other. At the crossover between embodiment and agency, resonance stirs the listener away from modernity’s cult of the eye and towards voices circulating between bodies and signs.

Drawing on these terms and the intertwined discourses on historical time and attunement, this essay addresses the ethics of complicity and engagement put forth by Portuguese-born, London-based visual and sound artist and electro-acoustic composer Diana Policarpo (b. 1986, Lisbon). Marked by an attempt to listen to the “the small voice of history, [1] the essay intends to challenge assumptions that affect is a private or bilateral matter, and that, instead, it is pivotal towards narrating a different history of composition and capitalist development in sonic practices. Policarpo’s artworks conceive an auditory position wherefrom listening to “the refrains and the reverberations by which we latch onto the world and each other, [2] emerges as an encounter between feminist theory and archival contributions that reach out beyond the musical canon. While Policarpo’s practice embodies a cinematic strategy that combines both visual and aural approaches, I argue that this arrangement confounds possibilities of representation, which in Western culture have historically privileged visual and spatial conceptions of communication. As Brandon LaBelle thoughtfully writes in his recent monograph on sonic agency:

“As forceful movements—of rhythmic and resonant intensities, of vibrational and volumetric interruptions—sound works to unsettle and exceed arenas of visibility by relating us to the unseen, the non-represented, or the not-yet-apparent; alongside spaces of appearance, and the legible visibilities often defining open discourse (…). [3]

From Descartes to Deleuze, resonance and aurality have been central concerns in discussing embodied reason. In Compendium Musicae (1618), Réne Descartes writes, “The human voice seems most pleasing to us because it most directly conforms to our souls. By the same token, it seems that the voice of a close friend is more agreeable than the voice of an enemy because of sympathy or antipathy of feelings [4] Implied in Descartes’ entanglement of affect and hearing is dialogic consciousness and the fleeting intensities in sensation and thought that illustrate the capacity for a body to be affected and to affect. This seems to suggest that affect and embodied hearing are not only the very materiality of auditory perception, but also the curveball of ethical practice.

While, on the one hand, Descartes’ comment invokes physical experience, namely resonance, which the Oxford Dictionary of English describes as the “reinforcement or prolongation of sound by reflection from a surface or by the synchronous vibration of a neighbouring object,” it also recalls debates on attunement. a privileged term in philosophy to speculate on the directionality of listening. Addressing the former, the Dutch scholar Veit Erlmann notes, “resonance is eminently suited to dissolve the binary of the materiality of things and the immateriality of signs that historically have preoccupied feminist discourse" [5]. He continues,

“(…) in marked contrast to the philosopher’s famous assertion that the only “inaudible foundation of truth” rests in the fact I am a thinking things and that this res cogitans is “entirely and truly” distinct from the body and “can exist without it”. Although the word indubitable has become a commonplace in modern translations, Descartes’ preferred Latin term is inconsussum (unshakable). Derived from the root –cutere (to shake violently)." [6]

Ultimately, in re-reading Descartes’ writings on music and sound against his notorious Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), where the philosopher contrasts vision and hearing as unequally privileged processes of accessing reality, Erlmann argues that, even in Descartes, this percussive movement is a legitimate object of knowledge. Erlmann’s argument draws on a close historical reading of inconsussum and its uses in modern astronomy to conclude that “various cognate forms of -cutere permeated scholarly discourse during the Scientific Revolution.” The rhythmic episteme implied in Erlmann’s argument is fundamental also in understanding the second reading of Descartes via attunement, the unfolding of new ways of living by attending to actualities and intensities. Communications scholar Lisbeth Lipari, for instance, reconciles both in articulating ‘interlistening’ here rehearsed as ethical statement and relay between between body and mind, and as politics of operation and possibility:

“Just as intersubjectivity describes the way dialogic interactions transcend simple boundaries between self and other, so interlistening describes the ways dialogue transcends boundaries of time, place, and person. Interlistening thus aims to describe how listening is itself a form of speaking that resonates with echoes of everything heard, thought, said, and read. (…) Interlistening thus brings multiple emphases on the inter of interaction, interdependency, interrelation, intersubjectivity as well as an acknowledgment of the attunement, attentiveness, and alterity always already nested in our processes of communication." [7]

In this scenario, how, then, can we accord the intensities of sound with the permeating boundaries of resonance that operate as a determining force? The canonical examples of the second half of the twentieth century have mostly positioned sound away from embodiment. John Cage, for example, referred to technology’s ability to “liberate” sounds from objects, with sound having no necessary relation to the aural context in which it first occurred; [8] Pierre Schaeffer also advocated for the neutrality of sound, distancing the listening experience from its visual apprehension, using the term acousmatic to define the unmediated perception of sound: “Acousmatic, adjective: referring to a sound that one hears without seeing the causes behind it." [9]

Yet, a number of their collaborators had contrasting views of sonic experience: Eliane Radigue (b. 1932) studied with Pierre Schaeffer in the 1950s, going onto be an assistant for fellow musique concrète initiator Pierre Henry in the 1960s. Radigue’s work which, at that time, included splicing and manipulating sounds with tape loops and microphone feedback, was met with hostility by Henry and Schaeffer who accused her of moving away from the movement’s ideals. Closer to the 1970s, Radigue relocated to New York where she became acquainted with the minimal composers and discovered the ARP 2500 modular system, a synthesizer that would define her aesthetics. Working in solitude and over great periods of time, her compositions are a slow unfolding of sound, developed from an overtly and deeply engaging experience with loneliness and Buddhist meditation. [10]

The latter two are fundamental experiences that traverse the continuum of several of other female figures from the emerging field of electronic music. Alice Coltrane (1937-2007), spiritual name Turiyasangitanada, was a composer, harpist, pianist, and organist who was deeply involved in experimenting with Indian, African, and Middle Eastern music, having heralded the term ‘spiritual jazz.’ In 1965, she married John Coltrane, and after he passed away two years later, Turiya raised their three children (alike Radigue, who had married French artist Arman and raised their three children in the French country side) and embarked on a solo career influenced by her spiritual path and Afrofuturist voyages. On the opposite coast of the U.S., Maryanne Amacher (1938-2009), who had been a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen and a collaborator with Cage and Merce Cunningham, composed sounds that lingered at the edge of auditory perception, responding to what she termed “psychoacoustic phenomena": A corporeal event defined by a vibrating mechanism within the cochlea, an organ of the inner ear, that provides acute sensitivity in the mammalian auditory system and causes a sensation similar to altered states of consciousness. Amacher’s views were closer to that of Stockhausen, who saw no difference between his body, his compositions, the inner nature of the sounds, their spatial source, the organization of the universe and the force unifying all: “We are all transistors in the literal sense…" [11]

These three figures had a significant understanding of sonic agency as embodied phenomena and how it relates to the general development of capital’s rule at the beginning of our century, which has been approached through a continued occlusion of embodiment as a foundational process that reveals the structural conditions of post-colonial capitalist societies. From as early as the 1970s, feminist theory has showed the possibility of intersecting the dichotomy between patriarchy, class, and race, overturning the obliterations put forth by critical theory, namely by Michel Foucault’s analysis of power techniques that have perpetrated the body in the modern era. Silvia Fredereci, Paul B. Preciado, and Denise Ferreira da Silva, among others, have showed how forceful attacks to the body during the earlier stages of capitalist development, from colonization to expropriation, were foundational to “primitive accumulation.”

But these authors have also foresaw hypotheses of alternative ‘forceful’ movements resting on trans-temporal solidarity, historical revision and activism.

Attuning to vulnerable figures, to the precariousness of female bodies working as unwaged labour and women’s historical exclusion from capitalism development (also in Marxist and post-structuralist accounts) is vital to rehearse conditions through which we can engage practices of rescuing from, resisting to and sounding the canon. As Brandon LaBelle sensitively notes, “Sound teaches us to be weak, and how to use weakness as a position of strength." [12]

After Descartes’ provocation, the harmonious sound of a friendly voice arises as the outcome of auscultating sentiments of support, solidarity and kinship, whether these are mutual in expression or historically coeval. In the past four years, Diana Policarpo has been engaging with the archives of German-American ultra-modernist composer Johanna M. Beyer (1888-1944), an earlier and pioneering figure in the field of orchestral and electronic music. After becoming acquainted with the composer’s pieces in a sound compilation from 1977, Policarpo engaged in dedicated archival research in New York and sought to expand on her notes and materials through a series of works “carefully composed and carried out, which are recorded and repeated in the exhibition's space,” notes the artist in email correspondence. Policarpo became interested in Beyer’s unrealised political opera Status Quo / Music of the Spheres (1938), a Gesamtkunstwerk, which was lost for over 70 years and became the material source of Policarpo’s six audio channel and four seated sound-sculptures, visual scores casted in steel, and immersive blue glass surface of Sun in Cancer (2016).

Policarpo speaks of her compositions and visual artwork as “hosts to research,” rendering her installations not as renditions or reinterpretations of Beyer’s work, but rather, as narrative account of the broader conditions in which her work unfolded. Here, the artist adopts a fine analysis of the processes of subjectivation associated with capitalist governance and, as Italian philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato remarks, Policarpo creates a stage for “the relation between discursive and non-discursive, conceptual and existential [that] should not end in silence (…) but must be worked at, conceptualized, semiotized, staged, narrated, etc. starting from the unrepresentable. [13] In Sun in Cancer (2016) and Dissonant Counterpoint (2017), Beyer’s ghostly sounds are reconstructed from the original score and her personal exchange with the ultra-modernist composer Henry Cowell and colleagues, resonating in a sensible field—an ethics of complicity—with the counter-voices of History, which allows affective expression to emerge as attunement—to the silence, the silenced and the underheard.

As Nikita Dhawan sensibly argues, “One who can be silent, is in a position to listen, and one who listens, gives oneself over to the silences in discourses — the elusive as well as the ordered silences, the silences that are subject to our will and those that govern our language, our being." [14]

Most of Beyer’s compositions remain preserved solely as graphic notations. Featuring in Sun in Cancer (2016), Status Quo / Music of the Spheres was written in the years between her diagnosis with a chronic nervous disorder and her death in 1944. And it wasn’t until 1977 that the unfinished piece was arranged and premiered in California. Dissonant Counterpoint (2017), an electroacoustic composition for nine multi-channels features Beyer’s Total Eclipse (1934), Universal-Local (1934), Two Movements: Three Songs for Soprano and Clarinet (1934-38), and Policarpo’s own The Spheres (2017).

Dissonant Counterpoint also renders visible her unrequited amorous correspondence with Cowell, from which fragments resonate in sound sculptures, whilst excerpts from the opera appear as quotations in a LED board as scrolling text. In her letters, Cowell emerges as an obsession and obstruction, but, most importantly, as Beyer’s awareness of his inevitable reference and her own access to legibility in historical time. As E.C. Feiss notes, “What we know from the revisionist histories of Beyer currently taking place (their aim an intervention into the narrative of modernist music) is that she took up a post of (unpaid) support to Cowell. She is reclaimed from behind the veil of feminized administration that so often characterizes the fate of women prior to the invention of their history" [15] Curiously, after the Mayor of Leipzig visited Policarpo’s installation at the Kunstverein, a plaque in homage to Beyer’s work and life was erected in that city, a redeeming gesture that resonates with Policarpo’s multi-channel and mixed media installation Visions of Excess (2015) where the artist pairs George Bataille's The Accursed Share: an Essay on General Economy (1946-49) with Silvia Federici's Caliban and the Witch (2004) a key feminist analysis of the history of women's oppression in capitalist development.

In a sonic practice of aural communion, tuning in to the world is to draw attention to the intricate relation between language and speech, power and violence, legibility and inequity. Building on Susan Sontag’s provocation “Silence is the artist’s ultimate other-worldly gesture, [16] attunement is foundational to any auditory position, which in Policarpo’s practice is announced as in and of itself. To this question—the rapport between sonic expression and the body and affect as a means of communication with the world—Policarpo’s artworks proposes a complex ethics of sonic thought and materiality. Previously parsed by the dawning discourse of the Enlightenment, the mind and the ear in unison radiate the impossibility of containing singularity. Intimately entangled, resonance and attunement are the bastions of its alliance.

Notas:

[1] Expressão de Nikita Dhawan (2012) citando os escritos de Ranajit Guha.

[2] LaBelle, Brandon, Sonic Agency (London: Goldsmiths University Press, 2018), 12.

[3] Ibidem, 2.

[4] Descartes, René. “Compendium musicae (1618)” in Charles Adam and Tannery, Paul (eds.) Ouvres de Descartes. Paris: Léopold Cerf, 1897. 79-141. Online.

[5] Erlmann, Veit. Descartes’s Resonant Subject. Difference: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. Volume 22, nos. 2 and 3, Brown University, 2011. 13

[6] Ibidem, 15.

[7] 512. Ênfase original do autor.

[8] Dyson, Frances. A Philosophonics of Space: Sound, Futurity and the End of the World, 3

[9] Schaeffer 1966: 91

[10] Wyse, Pascal. “Eliane Radigue’s brave new worlds” in The Guardian, June 16 2011. Online.

[11] Stockhausen: Conversations with the Composer, Jonathan Cott, Simon and Schuster, NY 1973, 37

[12] LaBelle, Brandon. Sonic Agency (London: Goldsmiths University Press, 2018). 20

[13] Lazzarato, Maurizio. ‘“Exiting Language”, Semiotic Systems and the Production of Subjectivity in FélixGuattari’ in Cognitive Architecture: From Biopolitics to Noopolitics: Architecture & Mind in the Age of Communication and Information, ed. by Deborah Hauptmann and Warren Neidich (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2010). 108

[14] Nikita Dhawan. “Hegemonic Listening and Subversive Silences: Ethical-political Imperatives.” In Alice Lagaay and Michael Lorber (eds.) Destruction in the Performative, Vol.36. Leiden: Brill, 2012. 59

[15] E.C .Feiss. “Johanna Magdalena Beyer, Music of the Spheres”.

[16] Susan Sontag, The Aesthetics of Silence in Studies of Radical Will, capítulo 1. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1969. 5

Footnotes:

[1] Expression borrowed from Nikita Dhawan (2012) citing Ranajit Guha’s writings.

[2] LaBelle, Brandon, Sonic Agency (London: Goldsmiths University Press, 2018), 12.

[3] Ibidem, 2.

[4] Descartes, Réne. “Compendium musicae (1618)” in Charles Adam and Tannery, Paul (eds.) Ouvres de Descartes. Paris: Léopold Cerf, 1897. 79-141. Online.

[5] Erlmann, Veit. Descartes’s Resonant Subject. Difference: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. Volume 22, nos. 2 and 3, Brown University, 2011. 13

[6] Ibidem, 15.

[7] 512. Original emphasis by the author.

[8] Dyson, Frances. A Philosophonics of Space: Sound, Futurity and the End of the World, 3

[9] Schaeffer 1966: 91

[10] Wyse, Pascal. “Eliane Radigue’s brave new worlds” in The Guardian, June 16 2011. Online.

[11] Stockhausen: Conversations with the Composer, Jonathan Cott, Simon and Schuster, NY 1973, 37

[12] LaBelle, Brandon. Sonic Agency (London: Goldsmiths University Press, 2018). 20

[13] Lazzarato, Maurizio. ‘“Exiting Language”, Semiotic Systems and the Production of Subjectivity in FélixGuattari’ in Cognitive Architecture: From Biopolitics to Noopolitics: Architecture & Mind in the Age of Communication and Information, ed. by Deborah Hauptmann and Warren Neidich (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2010). 108

[14] Nikita Dhawan. “Hegemonic Listening and Subversive Silences: Ethical-political Imperatives.” In Alice Lagaay and Michael Lorber (eds.) Destruction in the Performative, Vol.36. Leiden: Brill, 2012. 59

[15] E.C .Feiss. “Johanna Magdalena Beyer, Music of the Spheres”.