Review — by Ana Salazar Herrera

To step into Greenhouse is to immerse yourself in an abundant, living testament to resistance and interconnectedness. This ambitious and collective project reflects on the ecology (from the ancient Greek word “oikos”, which means “home”) of a house, a home, which is, as theorist Gayatri Spivak puts it, a place where you don’t need to justify yourself to strangers. It is a space for encounters where the biographies and personal relationships of the three authors of the Portuguese Pavilion have served as starting points to create a space of refuge. Artist and curator Mónica de Miranda, historian and social-political organiser Sónia Vaz Borges, and choreographer and researcher Vânia Gala explore together spiral axes of time and space related to shared histories. In the year that Portugal celebrates the 50th anniversary since the Carnation Revolution of 25 April 1974, which liberated the country from a four-decade long fascist dictatorship that was waging wars against the liberation movements in the colonies, it is an important and strong signal to have a collective from the African diaspora represent the country at the Venice Biennale.

Essay — by Paula Ferreira

Transcending the hermeticism of the exhibition space and the sacredness of the artwork, Portugal's participation at the 60th Venice Biennale, taking place between April and November, is redefined by a Creole garden housing a living archive, a school, and assemblies. A transdisciplinary conception, the GREENHOUSE project is born from a collaboration between Mónica de Miranda, Sónia Vaz Borges, and Vânia Gala's, bringing different areas of artistic knowledge together. Rooted in the principles of transversality and radical solidarity, and in a collective formed by a visual artist, a researcher, and a choreographer, Portugal's representation obliterates hierarchies—between curator and artist, nature and culture, thought and practice—and points towards what can be imagined as an artistic proposal for the future.

Essay — by Eduarda Neves

Dear friend, the last time I wrote to you I had just arrived from Paris. I told you about the Louvre exhibition, LES CHOSES: Une histoire de la nature morte. A year has passed since, a long time without sending any notice, prevented as I was by a vortex of exceeding tasks. Curiously, some works by a French artist that I had the opportunity to see in an exhibition running simultaneously with the Venice Biennale 2024—presented at the Punta Della Dogana Museum, formerly a customs building—led me to resume our correspondence. Although Foreigners Everywhere was the theme of the Biennale, it was almost exclusively in Liminal, Pierre Huyghe's individual exhibition, echoing some of the world's helplessness, that I found the resonance of Deleuze's words when, recalling Proust, he said that a writer is always a foreigner in his own language. This doesn't mean writers mix a new language with the native one, but that they put all linguistic forces into a minority that belongs only to each of them. This is the condition for a minor art, one that is capable of inscribing subjectivity on a transindividual scale.

Interview — by Maria Kruglyak

Oscar Murillo’s Together in Our Spirits at Fundação de Serralves—Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art brings the artist’s aesthetic investigations to Portugal for the first time. The show marks a decade of the long-term public work Frequencies (2013–2023), which serves as both entry and conceptualisation of the exhibition journey. Bordering community art, the work has the strongest connection to the early investigations that first got the artist famous, with big groups of people entering his practice as makers, creatives, and participants through what he calls the “working-to-work” process.

Interview — by Maria Kruglyak

João Laia’s inaugural show as Director of Galeria Municipal do Porto, forms of the surrounding futures, brings a very sensory, experimental take on queer exhibition-making. Understanding queerness through “an expanded perspective on futurity, as it’s something which is not yet defined and cannot be defined” Laia attempts to intertwine various strands of contemporary art through a multi-sensory, material-bodily experience. Leaning on thinkers such as José Esteban Muñoz, Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro to explore questions of futurism, Laia embraces queerness as something that, to be politically relevant, needs to go beyond identity towards a “forward-thinking positioning [… to paraphrase Muñoz] communities and audiences are much wider than we can recognise now.”

Review — by Maria Kruglyak

Dozie Kanu’s Preenchendo Vazios—Filling Voids in English—is refreshing in its contemporaneity and emotional subtlety. Exhibited at Espaço Lumiar Cité in northern Lisbon, it is a social statement of new materialism infused with an acute understanding of its context both locally and beyond. With sculptural works informed as much by art as by installation and interior design, the pieces are stacked to the brim with multi-directional references neatly compiled into a minimalism of the artist’s earlier practice. Above all, Preenchendo Vazios speaks a visual language that feels very now—a leap beyond postmodern sculpture in the expanded field.

Interview — by Margarida Mendes

Displaying works by Indigenous practitioners from the Pacific Latai Taumoepeau and Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta, the exhibition Re-Stor(y)ing Oceania embraces the medium of the oratory, the song, genealogy, performance, and embodied knowledge as pivotal. It explores how ritual practices and communal spaces may reconnect one with a deeper sense of custodianship.

Essay — by Valerie Rath

I can always grow up again. This thought solidified in my mind after visiting the group exhibition Lettera d'amore, curated by Alberta Romano at the Kunsthalle Lissabon, which featured works by the artists Alice dos Reis, Tamara MacArthur, La Chola Poblete, Laure Prouvost, Giulio Scalisi, and Inês Zenha, all of whom had previously been invited to the institution for a solo show. It's the first of a series of three group shows this year curated by three different curators—Alberta Romano, Yina Jiménez Suriel, and Filipa Ramos—as the Kunsthalle Lissabon pauses its regular programme of solo exhibitions to celebrate the fifteenth anniversary of the institution. I can always grow up again.

Review — by Maria Kruglyak

Unfolding material connotations, social codes, and the impermanence of human-made objects or interventions, Gonçalo Sena’s art practice has a magnetism that feels as grounded as it does conceptual. In person, the artist is as generous and softy direct in his speech as the visual poetics felt in his work. Seeing his art has the same effect as listening to him describe his practice: constantly searching for the exact gestures and welcoming multiple viewpoints. Throughout his work, philosophical poetics and context sensitivity shine through in accepting the impermanence of all things and artistic explorations of temporalities.

Review — by Valerie Rath

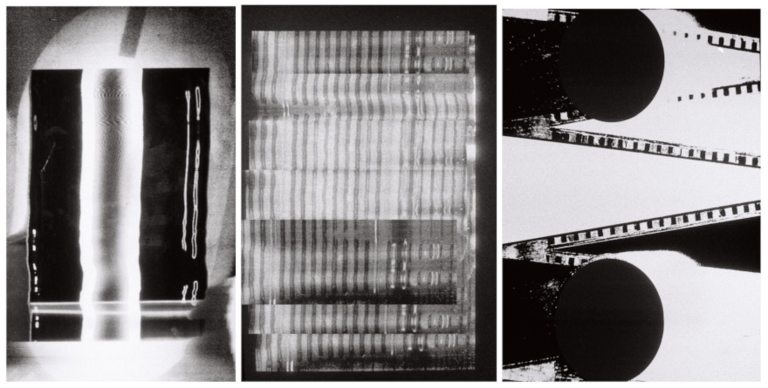

For his solo exhibition Airs at Galeria Vera Cortês, Portuguese artist Nuno da Luz works with highly reduced audiovisual media, where this reduction of means leads to an intensification of their symbolic meaning. However, the exhibition can be discussed within a broader framework than the purely work-immanent one, which revolves around the question of representation and the directing of attention. Since this exhibition is also about Palestine, it is precisely this "also" that I would like to address. Moreover, it is an exhibition that makes me reflect on hope, its sustenance and continuation, and our role in such an effort.. But let's start from the beginning.

Review — by Aishwarya Kumar

Igor Jesus’s Time Machine, originally titled Papagaio (Parrot), opened on 28 March 2024 amidst unprecedented weather conditions in Lisbon. At or around the same time Igor was testing the sound of the mixed-media sculpture, the curators stamping away bite-size information pamphlets in the Ping Pong room of Antecâmara, and audience members getting ready to step out into what was assumed to be the end of winter rains, motorists had spotted a “potential tornado” crossing the Vasco da Gama Bridge. This immensity went unnoticed by most who were engulfed in the opening. The hours before, a sacred time for curators and artists alike, is a long-standing moment of rituals, nervous break-downs, revelations, and disagreements, all of which, some may argue, feed the effect of the showing.

Review — by Valerie Rath

It's a beautiful Saturday morning. I sit on a terrace overlooking the rooftops of Lisbon, and I finally have time to start writing this text. I tried a couple times before but I wasn’t in the right mood to do it—not in the right emotional state to let myself sink into it. “so much to do / so much to feel / so much to be / so much to love / so much to enjoy / so much to devour and to be devoured,” as João Motta Guedes writes in one of his three poems that are part of his solo show No feeling is final—which this text is going to be about—at Galeria da Boavista, curated by Luís Silva.