Not Cancelled! — The Work of Art in the Age of Viral Propagation

Immunity will be the great philosophical and political question after the pandemic

[1]

I. Viral capital — Connection to the ventilator

A coronavirus claims its place in the world. In the world of contemporary art, too. To SARS-CoV-2, which has brought forth Covid-19, we owe a certain program of metaphysical unveiling. Affected by our condition of hidden hosts, we are unaware of the processes through which the parasite transforms us into its equal. A game where exchanges are potentially undetermined. Arriving as a parasite, it infiltrates in the constitutive fabric of each of us. Intimately, it alters or destroys us. Deploying a biological approximation, the virus, housed in the organism of the host, in its heideggerian condition of being-there and being-in-the-world, reconfigures the interdependent relationships we establish with capital.

Much has been written about the pandemic already. Geopolitical and philosophical perspectives of conspiracy, solutions for a better world, denunciations that capitalism is not a humanism after all. Everything has been postponed, rescheduled. However, it was all already there, before the appearance of SARS-CoV-2, before the health crisis made the system’s flaws visible: the unsustainability of the dominant mode of production we call capitalism, the crisis of financial markets, of agriculture, the crisis of health, of education, of transport and mobility, of work, unemployment and lack of purchasing power, industries that discharge tons of toxic waste into the atmosphere, excessive consumption of fossil fuels, climate change, the nuclear threat, population growth, inequalities in access to technology and the mystification of these same technologies, the weakness of the art world. History, as an inventory of problems, also shows us how to produce, master, and manipulate. Unsurprisingly, we are continuously given back the image of our own dissonant entry into the world:

"Man is a reserve, the strongest and most unified reserve in nature. He is a being-everywhere. And connected. United by a social contract, ancient philosophers observed, man is a great animal. From individuals to groups, we rise in height, but descend from thought into brute life, flamboyant or machinal, and it remains true that, by saying ‘we’, advertisement and the general public never really knew what they were saying or thinking; so we went beyond the critical dimension, but fell short on the scale of beings.” [2]

Social, political, philosophical, and economic theories have proved in recent months to be “capitalised”; few have not felt the subject as “urgent” and have not adopted the speed of the market. Regarding the pandemic, Graham Harman has said that “there are moments when each of us should simply be quiet and listen, and it's important to recognise those moments when they arrive”.[3] Perhaps the most immediately silent were the virologists and epidemiologists. The silence of those who have everything to do. To give time to the thought that is also action. Institutions, structures, and organisations endorse reinvention. “Reinventing”, as a stereotyped advertising slogan, becomes the empty watchword exhaustively summoned by the agents of the art world and beyond, thus assuming the return to a mythical time, originally perfect, which we would have unexpectedly lost. But we didn’t lose anything, because we hadn’t won anything. The history of capitalism is also the history of its permanent capacity to reinvent itself or, if we prefer, the history of its eternal return. There’s nothing new in the history of an economic system accustomed to crisis. The future will continue to belong to it.

Capital-sick, and often without recognising their own symptoms, artists, museums, galleries, foundations, and other structures in the visual-arts field have dedicated their respective confinements to the online promotion of streamings, virtual exhibitions, and openings, dissemination of collections and immersive tours, interactive catalogues and inclusive educational strategies. New audiences are claimed, art is propagated in the public space and in other varied urban projects. Some curators announce that, finally, the museum is everywhere. No one can be excluded from the game. The pandemic is not for experts. Instagram is our meeting place. The experience of an artwork is reduced to a like in a post. The dematerialisation of art turned into entertainment, pure virtuality in the form of content creation. Everything is appointed/scheduled, postponed and postponed again. And conversations, many conversations, in the form of ideas, conferences, meetings, debates, interviews, take place on online platforms. Artists, academics, museum directors, galleries, foundations, art fairs, programmers, collectors, curators, pro-active citizens, approach each other digitally, crossing experiences about art and public service. Communication, understood as an exchange of confident collective feelings in times of crisis, surpasses Netflix. The belief in the emancipatory potential of technology stages its interactive possibilities with art and yoga from home. Emerging digital artists replicate the leisure industry. Transformed into massmediology, the signifying machine in service of communication technology realises the illusion of progress and offers us technological operations as an experience that is at once mechanical, social, and economic. Everyone in front of a screen, artists and public, connected but disconnected. Online exhibitions, virtual exhibitions, become the paradigm of the experience of artworks that, transported to other geographies, other topoi, receive millions of visits. They promise other ways of seeing, a breaking with perceptive habits, a visual revolution in a single day.

Online visualisation, which turns presence into a disability. To experience, to look, becomes a way of navigating. Liking and not stopping. Without depth and without the depth of the surface, to summon Deleuze.

Experiencing the artwork as the thermal death of the business of art. The apparent democracy of machines dismisses us all. Offline. It doesn’t seem impossible to develop a whole new theory of Einfühlung capable of exploring these new relations between art and “distracted perception”, to write as Walter Benjamin. Unlike viral contagion, which acts through proximity, the online and massified experience of the artworks now makes them a kind of territory at a distance and without a battlefield.

Deterritorialized, the pandemic reterritorializes itself in cyberspace through the artworks that circulate the symptom which comes to us carrying our space-time shortcomings. They show us that it is the infinitely rich who continue to help the infinitely poor, repeating the lesson that without them we cannot keep living. Everyone kneels down. The fierce critics disappear from the gallery, the museum, the art market. Their importance is claimed, the capital remains the dominant resource, it becomes the mechanical ventilator of the artists, their vital factor. The machine that allows them to overcome respiratory failure. The promise of salvation that has always been. Capitalism, which annuls all collective effort, shows us that, after all, perhaps we are not all together:

“The construction of the reality of subjectivized capitalism is globally oriented towards competition for visibility. Visibility defines the spaces of action for the stimulation of impulses of envy—penetrating in the same way the terrain of daily consumer goods, money, knowledge, sports, art." [4]

II. From mass grave to group immunity

The internet is more and more sophisticated, it is archive and potency, it codifies the psychic instance of the master-slave dialectic, from which capitalism draws its strength:

“Maintaining order tends to depend less on military and policing machines than on the systems of regulation and normalization close to the people. In addition to some wild strikes and a certain incomprehensible percentage of delinquency, guided as they are by mass media, people keep themselves on a straight line by watching each other secretly. The alternatives between good, evil, social, associal, tend to be less prevalent than before. Therefore, dark fascism, the one with the swastika and the skull, has less chances of taking off." [5]

The uncertainty of global economy, economic scarcity, budget cuts, lack of public or private sponsors, repressive and micro-fascist policies, as Guattari wrote, will integrate art into the global world of services and servants. The ontology of online as psychopathology or as mass grave of artworks. The more life and art are diluted in the digital space, the more authoritarian is the neurotized propagation of corporate consensus to change communities, audiences, strategies, values, practices, institutions. This is the hegemony of neoliberalism in cyberspace, economic and monetary orders that take on the false appearance of a revolutionary

As a parasitic structure that reproduces itself in time, capitalism also reproduces itself in space. But by diminishing the possibility of globalization through travel, the art world will limit the physical proximity of connections.

Each one of us becomes a threat and will live without leaving home. Like SARS-CoV-2, we will be the image of capital, a living dead that covertly encloses us. This will be the next “glo-cal”. In a system where parasites parasite each other, is it necessary to protect the host, believing in the temporary failure that will lead to recovery, or is it necessary to introduce in the system a transformation so strong that it implies the destruction of both the host and the parasites? Surviving between invisible barriers, the parasite politicizes itself:

“In its own life and through its practices, the parasite currently confuses use and abuse; it exercises the rights it attributes to itself, damaging its host, sometimes without interest to itself, and could destroy it without realizing it. Neither use nor exchange are of value to him, because he immediately appropriates things, and one can even say that he steals them, harasses them and devours them. Always abusive, the parasite.” [6]

Confronting humanism as a perspective that places man at the centre of the universe – the heideggerian conception that takes it as a synonym for metaphysics or the tradition of humanism as “school of domestication of man”, as Sloterdijk has called it [7] — now, it’s thanks to a virus that another humanism is being contemplated: through digital platforms, the metaphysical dimension of technique is returned to us and the psychotic vocation of technology manifests itself, imposing its own code upon reality. It is this imperialism that promises to educate and promote rapprochement between men and people and access to art and truth, thus giving us back the image of capitalism as a ventilator through which we continue to breathe artificially. To not simply accept the order that precedes us and escape our own condition as a parasite is an overwhelming task.

If the virus can kill its host, it may also be able to free itself from the parasite. But a parasite can be understood as an element of transformation, “it interrupts a repetition and forks the series of iterations.” [8] Alexander Kluge said that, with the pandemic, reality is put to the test, and the challenge is to know what sort of public sphere we want afterwards: “like other infectious diseases, Covid-19 showed that, in the community, as in the territory of art, we are not immune, that our immunity is not sufficient or, we could say, there are not enough people to resist." [9] In March, I wrote that, against the virus of capital, only a pandemic virus would be able to immobilize us at the speed of light. I asked, then, what was one important political problem that, to this day, capitalism was able to solve. The question remains. I’m concluding this text on July 1st 2020. The United States have just announced the purchase of a huge stock of Remdesivir, the medicine used to treat critically ill patients with Covid-19, in an amount that corresponds to almost all of the production for incoming months. Capitalism does not need to reinvent itself and, again, will not pay the costs of its erosion:

“While biological immunity refers to the level of the individual organism, the two social immune systems have to do with super-organistic transactions, i.e. cooperative humane transactions: the solidarity system guarantees legal security, existential prevention and feelings of kinship beyond respective families; the symbolic system guarantees compensation for the certainty of death and the constancy of norms beyond the limits of generations. The same definition also applies here: ‘life’ is the successful phase of an immune system." [10]

Before any artistic claim, we face an ethical imperative. In art, as in life, only group immunity can assert itself as a collective defense against this infection. It is also immunity that summons an outdated name: humanity or, if we prefer, solidarity.

Traduzido do PT por Rômulo Moraes, revisto por Diogo Montenegro.

Eduarda Neves has a degree in Philosophy and a PhD in Aesthetics. She is a professor of contemporary art theory and criticism, an area in which she has published various works, and an independent curator. Her research and curatorial activity crosses the fields of art, philosophy and politics.

Notes:

[1] Peter Sloterdijk; Ana Carbajosa. “El regreso a la frivolidad no va a ser fácil”. Interview. In: El País, May 9, 2020.

[2] Michel Serres. O Contrato Natural. Lisboa: Edições Piaget, 1994, p. 36.

[3] Graham Harman, “Tecrit ve Tehdit [Lockdown and the sense of Threat]”. Interview. In: Baykuş: Felsefe Yazilari, May 6, 2020.

[4] Peter Sloterdijk. Cólera e Tempo. Lisboa: Ed. Relógio D’Água, 2010, p. 237.

[5] Félix Guattari. Líneas de fuga. Por otro mundo de posibles. Buenos Aires: Editorial Cactus, 2013, p. 129.

[6] Michel Serres. O Contrato Natural… p. 63.

[7] Peter Sloterdijk. Normas para el parque humano. Madrid: Ediciones Siruela, 2000, p. 52.

[8] See, for this purpose, the work of Michel Serres based on which we adopt this perspective: Michel Serres. Le Parasite. Paris: Hachette, 1997, p. 334.

[9] Alexander Kluge; Carla Imbrogno. Interview. In: Revista Ñ - Clarín, May 1st, 2020.

[10] Peter Sloterdijk. Tens de mudar de vida. Lisboa: Ed. Relógio D’Água, 2018, p. 551.

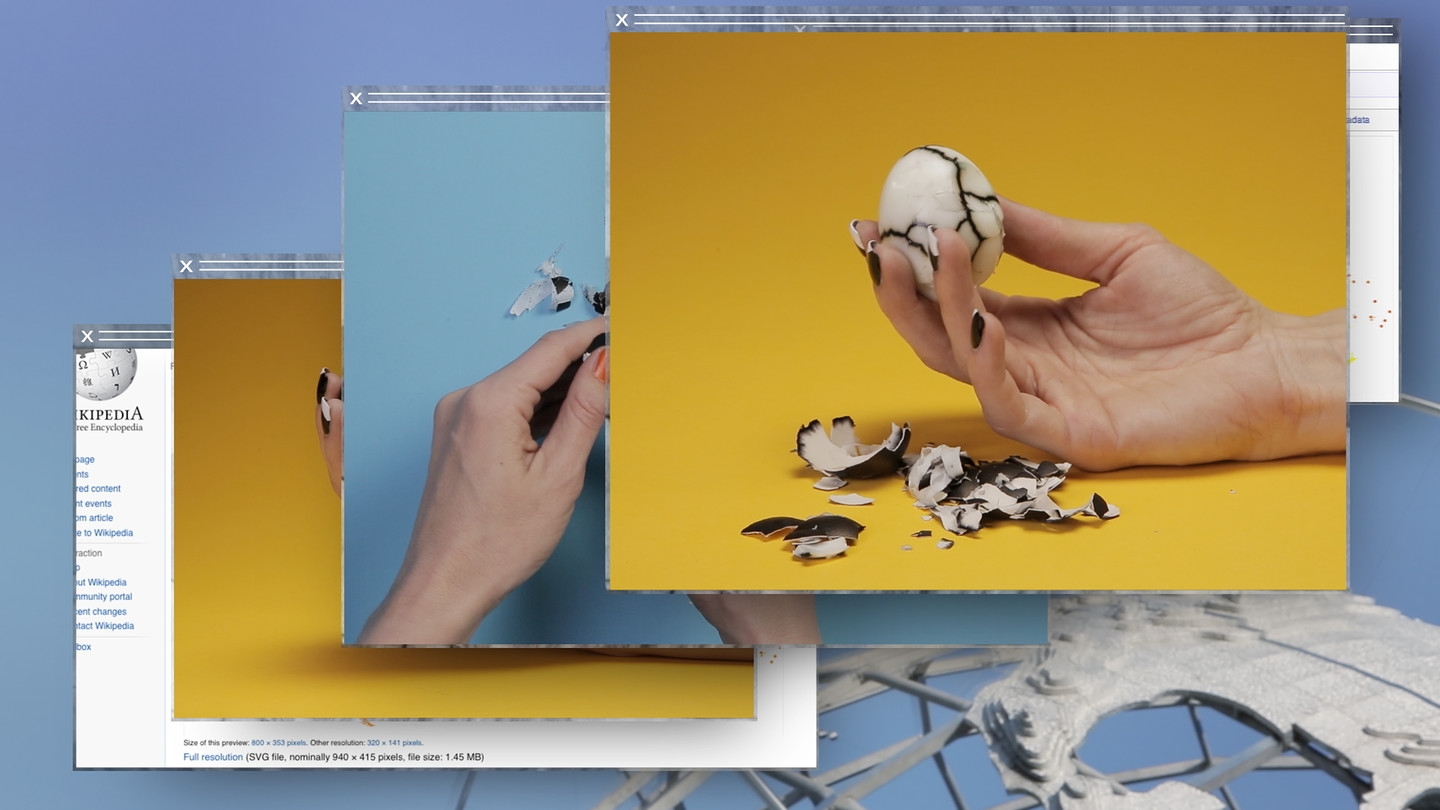

Image: Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue (still), 2013. Video, color, sound; 13:00 minutes. Courtesy the artist, Silex Films and kamel mennour, Paris/London. © 2016 ADAGP Camille Henrot.