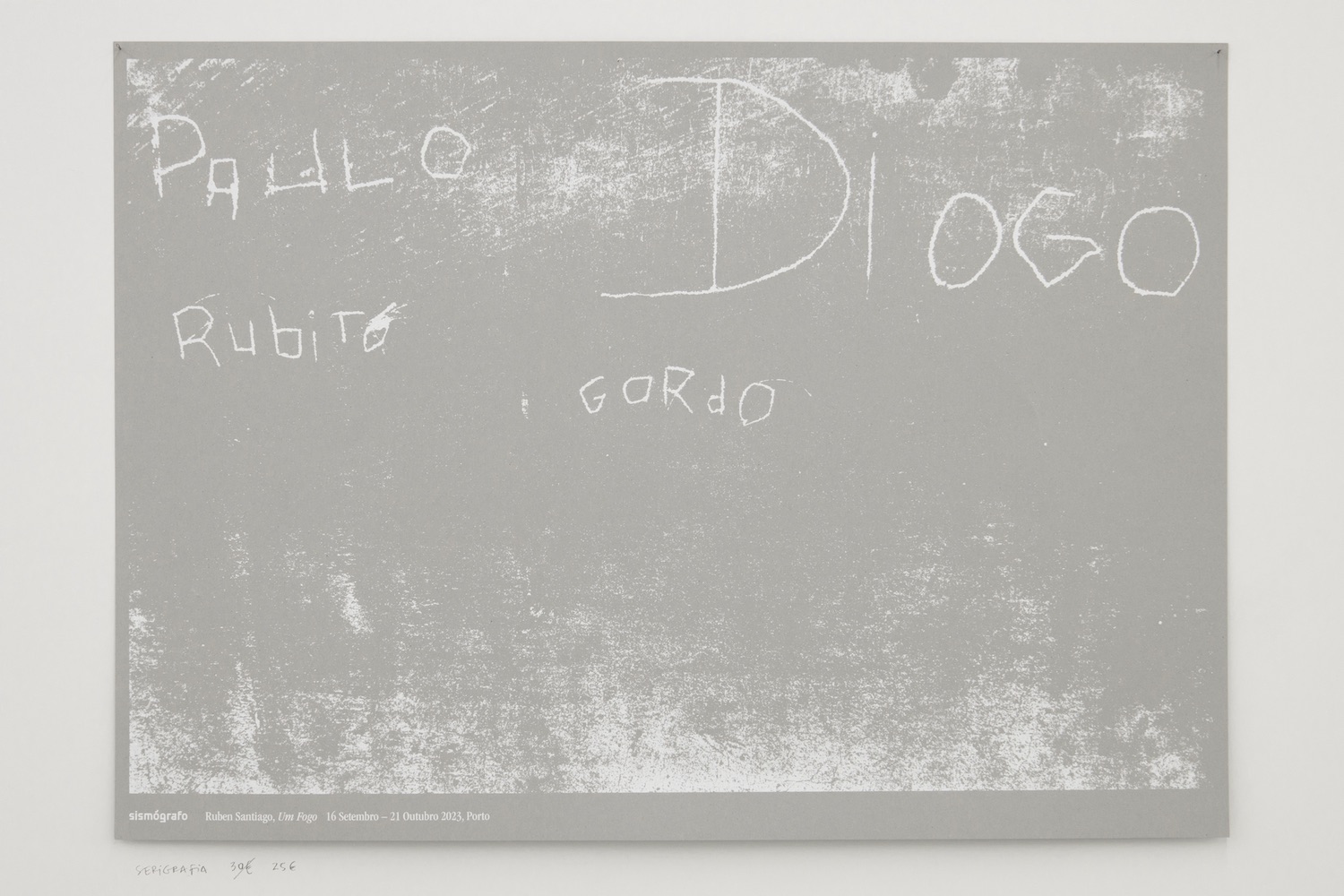

Ruben Santiago: Um Fogo

Ruben Santiago’s Um Fogo at Sismógrafo tackles the past, present, and future of housing by juxtaposing right by ownership with right by need and care, and historical lodging with current disuse. Striking a careful balance between precarity and resistance by revealing details and scale, it presents a powerful exhibition that is acutely aware of its context in Porto and in current discourse. The second show in Sismógrafo’s new space, Um Fogo is a counterpoint to the city’s gentrification, offering a critical voice from the contemporary art scene regarding housing and squatting rights and standing in vocal support of the plight of Stop, which is located some blocks down the street.[1]

Conceptually, the project is simple, as the most impactful projects tend to be. It is a reconstruction of the wooden floor tiles from two rooms of an abandoned bourgeois house that has since served as shelter, as the burnt traces of a fire on the floor tell us, and that is soon due to be destroyed to make space for, most likely, yet another hotel or unaffordable modern building. In practice, it took Santiago many nights to create a temporary studio in the building, but also required the artist to find his way into the abandoned house without anyone’s knowledge, as the locks melted down into powder and displayed under photo documentation in their previous form tell us. In order to reconstruct the beautiful wooden floor, Santiago numbered each of the tiles: 5227 in total. In their new location of a collectively run contemporary art gallery, the bright white numbers on the wooden tiles invoke a sense of perfectionist details, an obsession and exactness that feel so familiar in contemporary art spaces.

The perfectionism of the numbering is juxtaposed with the other traces that each of the wooden tiles holds: stories we cannot read, written in a language of feet and weight that can only be read emotionally unless aided by a detective’s lab. Squatting down by them, I was taken back to ways of thinking I had when I was a little girl: creating fantasies in abandoned buildings and making up stories of those who came before. In other words, historicising, but the way a child does—based on feeling and imagination. By numbering the tiles, Santiago places these touch-based histories in a consciously Western scientific narrative, a narrow world of alphabetised, classified, and strictly organised data. To some extent, this is out of logistical necessity: how else would he rebuild the tiles in the exact same way? However, it also serves to highlight the other, unclassifiable histories that defy the numbering and are readable by imagination only—fantasy overpowering the pattern of science.

The title of the exhibition is the trace of an open fire that breaks the pattern of the careful layout of the wooden tiles from the time of its first inhabitants. Presumably, the fire traces come from a more recent time when the abandoned house was occupied by someone in need of shelter and, clearly, warmth. Santiago tells me it was the traces of the fire that first caught his attention when he began his intervention in February 2023 with the intention of exhibiting the floor in a gallery space.

Playing with the multi-layered context of these stories and their classifications, with fire as the main character of the scene, Um Fogo allows the viewer to build interpretations and project imaginings onto the horizontal plane of the laid-out floors. An obvious such reflection is a tension that lies parallel to that between the scientific-numerical and the histories-fantasies: a tension between what is “right” by law and what is “right” by need in the context of the current housing crisis. Seeing the burnt locks of the house, we can imagine that the artist occupied the empty house as an artistic object—art acting as a protecting cloak in relation to the question of the legality of the artist’s trespassing—just as others have done before him out of need, as the fire indicates. In adherence with a rule of care that parallels much of the squatting movement,[2] the artist left the house in better condition than when he entered by cleaning up the space. Just as fantasy trumps science, so does care trump jurisdiction: one’s right to be in a space is stronger based on care (and need) than any legal right that leads to its disuse and disarray. As a slogan from the current housing rights movement reads, “Tanta casa sem gente, tanta gente sem casa” (lit. “so many houses without people, so many people without a house”).[3] Significant here is also the fact that the artist was not the first to enter the space: the house had already been occupied out of necessity (hence the fire) before being occupied for art, exploring the traces of this necessity, of that which came before, and of that which will come after.

This exploration of traces is a significant basis of the artist’s practice of urban drifting and exploration, which, in his own words, is his way of “relating to the city” he lives in and its urbanity. It is also not his first intervention on Rua do Heroísmo in Bonfim, Porto: in 2018, Santiago cleared Palácio Ford, the 800 sqm industrial space behind Stop, for a group exhibition entitled PARA INGLÊS VER_. The show opened the same week that the former car dealership changed owners, leading to an architectural contest for the building and the current multimillionaire real estate development that may well be the reason that the artist studio space Stop is now having to fight for its survival.[4]

Powerful in its simplicity, Um Fogo reformulates some of the most acute problems both locally and beyond in our relationship with the past, present, and future amidst rapid urbanisation, gentrification, and touristification. Through juxtaposition, it reveals that stories, imagination, care, and need remain more powerful than jurisdiction and scientific-obsessive classification when the latter does not fulfil desires of imagination and care—a crucial reflection in this time of financial, social, and cultural crises.

Maria Kruglyak is a researcher, critic and writer specializing in contemporary art and culture. She is editor-in-chief and founder of Culturala, a networked art and cultural theory magazine that experiments with a direct and accessible language for contemporary art. She holds an MA in Art History from SOAS, University of London, where she focused on contemporary art from East and South East Asia. She completed a curatorial and editorial internship at MAAT in 2022 and currently works as a freelance art writer.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro.

Notes:

[1] This is clearest expressed in Ruben Santiago’s workshop in conjunction with the exhibition Ornamentation and (is a) crime, on 21 October 2023 which intends to generate a collective archive of stickers and other graphic manifestations on Stop’s façade.

Stop is a car park turned 1990s-shopping-centre turned underground-cultural-centre, having become a cultural hub of Porto with its 126 shops being used as studios and other artistic spaces. Since being served a notice of its foreclosure, supposedly due to health and safety concerns, it has seen artists come together to protest for their right to remain in the space, urging the council to instead help make the space up to regulations. The expected eviction led Porto’s art and music scene to mobilise in a fight that has been ongoing for at least four years. Eviction notices were served earlier this summer, but currently Stop’s plight has been successful in convincing the Minister of Culture and the City of Porto to announce a cessation of the eviction indefinitely.

[2] Occupy movements have historically stemmed out of a reality where the capitalist requirements to be able to “compete” in the housing market are unattainable or unviable, combined with a refusal to be part of a system that is oppressive. Ruben Santiago speaks of the concept of care not in the context of squatting but in that of his personal philosophy: “I want to improve, no matter how temporarily, the conditions of those spaces for their current or potential future users, no matter if they are people looking for shelter or cat colonies. In this case, I did not only take the wooden floor, I also cleaned the entire house.” Quoted from a WhatsApp conversation with the artist (21 September 2023).

[3] The housing crisis in Portugal, exacerbated by rapid, unbridled touristification and lack of sustainable governmental solutions, has deepened in the past year with rent prices up at least 65% since 2015 and 37% during 2022. This has led to the average age that people leave their parental home reaching the highest in EU at 33.6 years of age. See Catarina Demony, Patricia Vicente Rua and Sergio Goncalves, “Young Portuguese defer dreams as housing crisis bites,” Reuters (26 March 2023).

However, the needed housing already exists, with an estimated 750,000 empty houses across the country. See Sam Jones, “Portugal’s bid to attract foreign money backfires as rental market goes ‘crazy’”, The Guardian (29 July 2023): theguardian.com/world/2023/jul/29/portugals-bid-to-attract-foreign-money-backfires-as-rental-market-goes-crazy.

Big protest movements such as Stop Despejos, Casa Para Viver, Casa é um Direito, Habitação Hoje, and many more, came together to organise the largest housing manifestation to date, which took place on April 1st. A second national-scale demonstration took to the streets on September 30th.

[4] From a WhatsApp conversation with the artist (22 September 2023) during which it was also announced that Stop, for the time being, will be allowed to continue to operate. See André Borges Vieira, “Encerramento do Stop está suspenso por tempo indeterminado,” Público (22 September 2023): publico.pt/2023/09/22/local/noticia/encerramento-stop-suspenso-tempo-indeterminado-2064273. Further information about the PARA INGLÊS VER_ exhibition is available on postfordpalace.wordpress.com.