Interview with Filipa Ramos

Filipa Ramos is a writer and curator—and an important critical voice in contemporary art and ecology discourse.[1] Influential in the international art scene, she also served as Director of the Department of Contemporary Art of the city of Porto, comprising the Galeria Municipal do Porto, until early this year. At the time of this interview, it had just been announced that the project Bestiari, with Ramos as curator and Carlos Casas as artist, had been selected for the Catalan pavilion at next year’s Venice Biennale.

I interviewed Filipa in conjunction with the opening of Dueto at Galeria Municipal do Porto, conceived during her time at the art centre and now curated by her. The show features two artists in a double invitation where a young artist from Porto, this time Maria Paz (b. 1998, Porto), invites an artist they would dream of sharing an exhibition space with, Joan Jonas (b. 1936, New York).

Maria Kruglyak (MK): It’s a pleasure to see a show that is so alive, light and playful—both in terms of the concept of the duet, with two artists “attuning their work to one another,” as you call it, and in terms of the works on display. How did the initial idea of Dueto come about?

Filipa Ramos (FR): It came from me thinking about what you could offer to someone young that allows them to grow their practice and be in dialogue with a reference of theirs. If I were to stay here [as director of the gallery], the idea would be to do this every year until we’d invited quite some young practitioners from Porto to do a project in collaboration with someone else.

MK: It’s really good supporting work, especially in that it circumvents what might otherwise be quite a strict mentorship relationship between the artists. In this show, the young artist from Porto is Maria Paz. How did you first come across her work?

FR: There’s a shop in Porto called Matéria Prima, which is one of the places here where I feel more at home. I first saw Maria’s ceramics in their vitrine and went to visit her studio at Zé de Bois in Lisbon. I was really impressed to meet someone so young and talented. It wasn’t only her work and its scale that impressed me, but also the capacity that she had to think about her practice in a very intelligent but also very sensible way. And since I was already thinking of who to invite as the first artist for Dueto, I thought Maria would be really interesting. So I asked her: “Who would you dream to share an exhibition space with?”

I really was not expecting her to say Joan Jonas. You know, if someone asked me who I would dream of writing a book with, I’d maybe say Donna Haraway, but I would also be too paralysed and intimidated to do that. But then Maria had the guts to say: “I saw a Joan Jonas show in Serralves, and it really inspired me. It would be amazing to do a show with her.” And I thought, "wow, you dream high!"

MK: Amazing. And you already knew Joan Jonas, right?

FR: Yes, I already knew Joan. One of the chapters in my PhD was on her, she was part of this big show I curated [at the Bildmuseet, Umeå, and the Baltic, Gateshead, in 2019–2020] called Animalesque, and I’ve also written about her work quite a bit. And so I went to New York to visit her, and amazingly she accepted.

Later, Maria met Joan in Munich, where Joan was having a major retrospective exhibition [at Haus der Kunst], so they spent some time together getting to know each other and discussing how to make the show. Their practices are very different: Maria works very much with clay and ceramics, and Joan works mostly with her own body, either performing or making drawings. Maria decided to make a big production of works for the show and spent all summer at Oficinas do Convento in Montemor-o-Novo making the big [ceramic] sculptures we see in the exhibition.

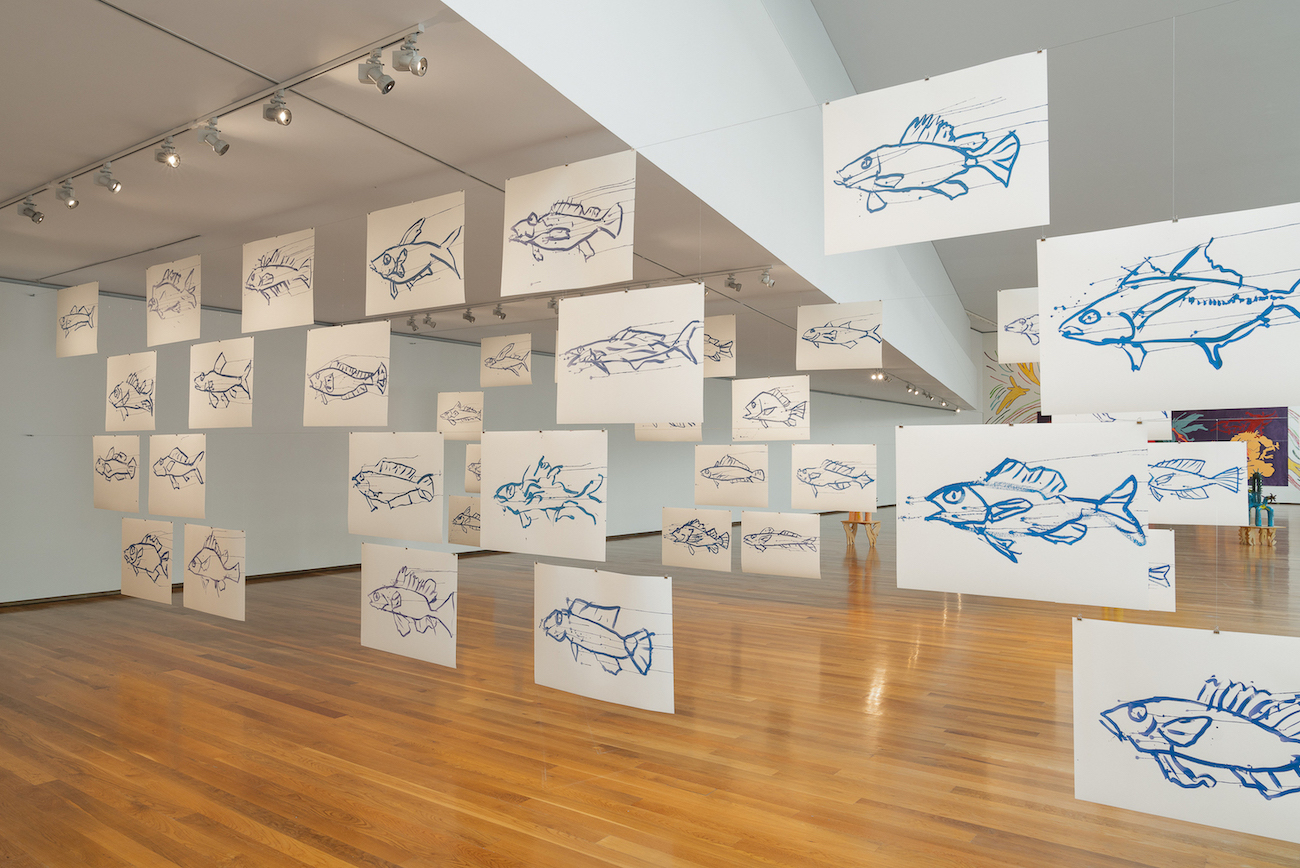

As for Joan, we decided to present two paper-based installations that had never been seen in Portugal before: the fish drawings that open the exhibition [they come to us without a word II (2013-2023)], which are from an installation that she made in Japan in 2013 and that had not been shown as a whole ever since, and Rivers to the Abyssal Plain [2021], the work on the first floor, which I, as part of the team of the 13th Shanghai Biennale, commissioned for the show but had never seen due to the pandemic. Part of it is a piece filmed with excerpts filmed at the Vasco da Gama Aquarium in Lisbon. Maria’s drawings on the first floor [Mátria (2021) and São as histórias que elas me contam (I – XXXVIII) (2023)] are in dialogue with this expressive, blue-and-white tradition of Joan’s they come to us without a word drawings. In choosing these works, I tried to create the spatial conditions for the two artists to come together. For Joan, it was important that the show would respect the balance and difference of the two artists: that her work would not dominate that of Maria, nor give visitors the illusion that they were making work together. Instead, it’s about two artists sharing the exhibition space, thinking together, attuning themselves to one another.

MK: When I was preparing for this interview and looking at the various shows you’ve curated throughout the years, I realised that you tend to have a theoretical underpinning that comes from a specific writer or critic. Was there anything you were reading or researching when you were creating this show?

FR: I don’t know how other people have ideas; mine come from reading and facing the brilliant ideas of other people. With this show, there was indeed someone who was really influential, although this isn’t stated anywhere and she doesn’t even know it—it’s the queer, Black, eco-feminist writer and incredible mind Alexis Pauline Gumbs. Throughout her life, Alexis has been researching the legacy and writing of postcolonial philosopher Sylvia Wynter. I hadn’t read Wynter before reading Alexis’ book Dub: Finding Ceremony [2020], where she digests Wynter’s legacies while bringing them forward to incredible new places, with the idea of writing with rhythm and of dub as a music practice that incorporates other people’s music while transforming it completely.

In a very shortened version, Wynter has the project to understand why there was a fiction written and told by Western white modernity—the fiction of the white man—that legitimised the oppression and subjugation of people deemed “Other.” How is it possible that the West constructed a fiction that became a reality and in which it was OK to dehumanise and treat other people like non-people? Asking this, Wynter decides to undo this story, but, she says, in undoing this story she is also undoing herself, as that is what she’s learnt. To undo this story, new stories are needed: stories that may not be understandable yet but need to be written. In Dub, Alexis places these stories in small rituals, in small messages. Some make more sense than others. Some, for example, are simply breathing exercises.

After reading Dub: Finding Ceremony, I started seeing Maria’s and Joan’s work as inspired by the possibility of telling stories that are strange and different or that don’t exist anymore. This book was my unstated, undiscussed inspiration and reference—the company that I’ve been keeping in making this show, as I’ve been reading this book while I’ve been thinking about it.

MK: Dueto is also a very choreographed show, architecturally specific in how the works are placed, such as with the Monstras [2023] marionettes in the liminal space between the window and the façade, as well as in the fact that you can never see the works of both artists at the same time. Instead, the relationship between the artists is very subtle, based on our memories and knowledge of the other’s work being there. Do you feel like the artworks in Dueto somehow changed by being shown together?

FR: I don’t know if it has to do with me reading Alexis’ book or with the pairing of the works, but I really started seeing these two artists as two people who are telling stories that don’t have a beginning or an end but are embedded in a desire to say something. You know, Joan’s fish [they come to us without a word II] are telling us something, they have movement; Joan’s video upstairs [Rivers to the Abyssal Plain] shows you things happening without you really understanding what. They seem to be rituals or fragments of private, ritualistic moments. The same happens with Maria’s work: they’re another part of the story with strange, carnivorous plants and reappeared monsters.

MK: For me, Maria’s ceramic works on the ground floor [2] and Monstras really read as part of a queer, feminist practice.

FR: Totally. Maria is always saying that her work reflects on the forms of the body of women from a perspective where there is a queer stance—but queer, in my opinion, in an expanded manner, both in terms of challenging gender normativity and in terms of thinking about relationships that are interspecies. It’s interesting how she chose the word "monster" in the feminine form: monstra. So they’re she-monsters. In general, monsters are always in-between figures: not fully animal, not fully human.

The pairing of these two artists made me think of these forms of elliptical and strange storytelling that can emerge with the practices of art. Stories that disrupt the expectations of a story and construct possible worlds: worlds of human emancipation, of celebration of queer and interspecies beings, of illusions to environments and the existences that environments host. On the one hand, these storytellings unite these works, and on the other both artists could easily be placed within a tradition of Surrealism. You can say that there is this Surrealism in these works or, if we see it the other way around: Surrealism is a movement that grabs something that exists before or after it. It is a desire to tell or see things differently, a deconstruction of the canons of what has been written, the way we see the world and the way things should be seen. And I think that these artists are doing exactly that by creating strange forms and rituals that we don’t completely understand. They’re altering the possibility of understanding and feeling things that may be strange but are also friendly.

MK: Turning now to the Portuguese context and the context of Porto specifically. You’ve spent quite a lot of time away from Portugal, but then you came back and were the director here, in Porto, and now you’ve left again—but you’re still involved in the art scene here in a lot of ways. What do you think we need in order to foster a thriving art community in Portugal? Because for me, who’s not from here, I feel that there is a huge amount of amazing contemporary art. There are a lot of very interesting people, and also a lot of people who are really trying and doing. But I also feel that a lot of people who work here are very despondent and find it very difficult to do the projects they want to do. As someone who’s been both inside and outside, what do you think would be the way forward?

FR: Porto has a very different context from Lisbon in the sense that, despite being smaller, proportionally the municipality has invested a lot more in culture. There are many more grants—not residencies, Lisbon has more structures for residencies and studios for artists in the city—in Porto in a conscious effort to create economic support.

But economic support on a small scale is not enough, especially in a country that is being so affected by touristification with the huge housing crises it creates—and that we’re experiencing all over the world but that affects countries differently depending on how much solidity there is for those who live here to claim their roots and to stay and not feel threatened.[3]

I think that if you only give out small-scale and not structural economic support, people get pushed out. To avoid kicking them out, you need, for instance, to create a system for state-controlled rent for cultural practitioners, or create commissions for dialogues that are transnational—which is a bit of what we’re trying to do in this show.

And I agree with you, I think there’s an incredible art and cultural scene in Portugal. But if we don’t create the conditions for it to be stable and also visionary in its dialogue with other contexts, it becomes very fragile, and things appear and disappear, or they are pushed into the underground. While Portugal is not a super wealthy country, it has invested a lot in helping people to go and study abroad, but now, with the current housing crisis, the country needs to create structural conditions for people to stay here. I don’t know if local governments would really want to do that. Because if you do, you’re emancipating cultural producers. So perhaps they think it’s better to give €1000 or €2000 and make sure that cultural workers stay dependent, so that they might hesitate before criticising those they depend on.

MK: Turning back to your own work, what have you been doing since you left Porto?

FR: Mostly, I went back to what I was doing before coming here: writing, because it’s very difficult to have time to write when you’re in an institutional position; teaching at the Arts Institute of Basel, where I used to direct the master’s programme (actually, Maria Paz is on a plane there right now as she’s about to start the school this year!); and embracing projects that I haven’t had time for otherwise. One such project is an ongoing collaboration I have with London-based Italian curator Lucia Pietroiusti. We created this kind of “creature” called The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish, which gives a platform for people from different disciplines—scientists, musicians, and botanists but also performers and writers—who share similar interests and questions to come together. We did a festival, and now we’re working on a book.

Together with Lucia, we’re also working on an exhibition called Songs for the Changing Seasons, which will be in Vienna this spring [2024] as part of the first Vienna Climate Biennale. The show thinks about the role that art can have in relation to the environment and ecology from a perspective that does not assume that art can help people to be more sensible or help us save something—but to admit that this already happened. The apocalypse happened to so many people already, and to so many non-human people; so many have been decimated and killed, their cultures erased. It’s just such a Eurocentric perspective to think only that the apocalypse may arrive for us. We’ve already been causing a lot of apocalypses. What if the end of the world has already arrived, how do we face that? How do we assume responsibility? How do we hospice the conditions that led us to be able to do this? And what is the road of artists and practices in accompanying us in this grief and mourning and thought about where we are?

MK: It’s interesting that you’re talking about the role of art in this because, in the last few months, there’s been something of a public debate in ecological art which, it seems to me, has divided people into two camps: some that believe that the time has come to not just put up eco-art exhibitions but to actually change things with our projects, and some that have been resisting this, saying that art is there to feel, to think, and not to serve a purpose. And I think that when you come from a point of view that we’re already in the post-apocalyptic reality, then even the active change is a sort of reflection of our time [in the post-apocalypse]. Where do you feel that “eco-art” is moving and what direction would you like it to take?

FR: It’s a very important question. While you were speaking, I was thinking about the lithium show you saw here earlier this year [Compulsive Desires: On Lithium Extraction and Rebellious Mountains], which is proof that art can do very little as the show was still on when the Portuguese government decided to give the green light to the mining companies [by approving Savannah Resources’ Environmental Impact Assessment for the open-pit mine in Covas do Barroso in May 2023]. So, I think that all the great ambitions for art do very little because, in the end, we live in a system—which is not by chance called capitalism—where money rules. And so, ironically and in a very pessimistic way, what art does well is to move money—because that’s how the world is managed. Everything we do continues to feed that system until we find something else. At the same time, if we don’t have poetry—seen in a general way as stories and storytelling of all kinds—then we have nothing left.

I’m also thinking about something I experienced for the first time when I was part of the curatorial team of the Shanghai Biennale in 2020. I guess I’m very privileged to come from a Western European context, as that was the first time I faced the strength of censorship with the Chinese government censoring a series of proposals we had for the show. And it was very annoying and frustrating, but at the same time I thought, “wow, they’re taking art seriously, much more so than anyone else.” If they censor it, they must believe that art can change something, that art can subvert or lead people to desire to subvert, that there’s some capacity for poetry to act upon the world.

I think art does not act in the direct way of self-service of transformation where you see something and then you change your behaviour. After all, we live in ways that are so micro and macro, with the micro being so small that we feel it changes nothing, and the macro being so big that we can’t even reach it. Instead, I think we need art or poetics as a way to think, a way to be conscious, and a way to face something that isn’t easy to face. And it’s very important that it’s not just an illustration of tragedy, what I call eco-porn, revealing the nastiness of the world we inhabit.

MK: Yes. This storytelling that you’re speaking of is also present in Bestiari, your and artist Carlos Casas’ winning proposal for the Catalan pavilion at the Venice Biennale. How did you end up working with Casas and what can you already reveal about the pavilion?

FR: Me and Carlos have worked together quite a lot. This summer, he challenged me to submit a proposal for the Catalunya representation at the Venice Biennale. I thought we didn’t stand a chance because he’s half-Catalan and, while he grew up in Barcelona, he lives elsewhere today; and, of course, I’m Portuguese. Anyway, we submitted, and we got shortlisted—which was already a big surprise—and then we got selected, which was like, wow!

The show is about something that Carlos found, and that I thought was amazing. It’s a story by Catalan mystic Anselm Turmeda [1355-1423], who was spiritually very interesting in that he converted from Christianity to Islam. Born in Mallorca, Turmeda spent most of his life travelling in the Mediterranean and then wrote this text between 1417 and 1418 in the tradition of the medieval bestiary. It’s called Disputa de l’ase in Catalan, which in English would be “the dispute of the donkey.”

The story starts with him falling asleep and waking up in the midst of an assembly of animals who are challenging him as to why humans feel superior to animals. There are 19 sections, and each section speaks of a different species: the way that bees build their communities, how ants treat their families, and how swallows are able to travel and come back to the same place. And he really knows his animals! We found it incredible, so we decided to create a big opera around this story using a sound system called ambisonics and sound recordings of seven different animals from Catalunya—both local and those considered invasive—who express themselves in cries we cannot understand.

MK: Wow, sounds fascinating. I’m really looking forward to seeing it. And a big congratulations!

Maria Kruglyak is a researcher, critic and writer specializing in contemporary art and culture. She is editor-in-chief and founder of Culturala, a networked art and cultural theory magazine that experiments with a direct and accessible language for contemporary art. She holds an MA in Art History from SOAS, University of London, where she focused on contemporary art from East and South East Asia. She completed a curatorial and editorial internship at MAAT in 2022 and currently works as a freelance art writer.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro.

Dueto, Exhibitions views at Galeria Municipal do Porto, Porto, 2023. Photos: Dinis Santos/Galeria Municipal do Porto. Courtesy of the artists and Galeria Municipal do Porto.

Notes:

[1] Filipa Ramos has worked extensively as a curator, writer, editor, and researcher in Europe and beyond, notable for curating the seminal “Animalesque” exhibition at Bildmuseet (2019), co-curating the 13th Shanghai Biennale “Bodies of Water” (2021), curating Art Basel Film, and curating the festival “The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish” (2018-ongoing) together with Lucia Pietroiusti, with whom she also curated the 8th Biennale Gherdëina “Persons Persone Personen” (2022). She has contributed to and edited a myriad of art critical journals and worked as editor-in-chief of art-agenda/e-flux (2013-2020), associate editor of Manifesta Journal (2009-2011), and editor of Animals (Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press, 2016). She is the author of Lost and Found (Silvana Editoriale, 2009) and the forthcoming The Artist as Ecologist (Lund Humphries, 2024). As a lecturer, she has directed and now teaches at the Master Programme of Institute Art Gender Nature FHNW Academy of Arts and Design, Basel.

[2] Maria Paz’ glazed ceramic works featured in the Dueto exhibition are the following: A Seed’s a Star (2022), Cavalo de Tróia. Queres leitinho? (2022), Como una yegua del Apocalipsis (2023), Laura (2022), Me sube el picante (2023), Memória de um sonho molhado (2023), São línguas os tentáculos da Medusa (2023), Steege (2022), The Distance of the Moon (2023), Venus’ Flytrap and the Bug (2023). Not covered in the interview is also the large-scale mural composition in the far end of the ground floor, A receita do Húmus (2023), that guided the perception of the exhibition as a celebration of diverse, strange forms of being.

[3] The example Filipa Ramos gives is a comparison with Vienna: “In a city like Vienna, which has a very solid middle class and state-controlled rents, tourism is not dismantling the solid base of those who live there. In Portugal, on the other hand, rents were very cheap and houses were very cheap, and now all of a sudden there’s tourism without enough solidity for those who live here to claim their roots and to stay and not feel threatened.“