PLEASE HOLD

Curated by Diogo Pinto, PLEASE HOLD is a group exhibition expanding on cultural assimilation protocols through a nuanced analysis of waiting.

Running from 27 November 2022 to 1 January 2023 at Ausstellungsraum Klingental in Basel, it recreates the experience of physically-lived bureaucracy—waiting rooms designed to provide the bare minimum of comfort, impersonal offices decorated with artworks from public collections, the bureaucratic processes experienced by immigrants and nationals alike and the strange environments flourishing from such systems.

Porta da rua é serventia da casa,

or

a universe of regulations

When I first moved to Switzerland, Diogo Pinto had already been studying there for about a year. He introduced me to the bureaucratic dance of residence permits, mandatory health insurances, rental agreements, and Swiss life-hacks for immigrant students. No doubt: previous experiences in Portugal had strongly shaped Diogo’s approach to bureaucracy even after the move to Switzerland. I knew of his love for the architecture and furniture of public spaces—a quirky interest—with a knack for the falling-down-a-rabbit-hole kind of research and a trained eye for the absurd. The apple of his eye: office scenarios and waiting rooms, a fixation recently renewed thanks to mandatory visits to such environments in a foreign country while getting accustomed to a whole new system. Prepped by Diogo’s tales of the Migration Office, it was soon time to make a visit there myself.

Basel, considered a somewhat “friendly” Swiss canton, is located near the trinational region where Switzerland meets France and Germany. The city’s name is frequently thrown around in association with mega art fairs or big pharma; corporate high towers, built in record time, punctuate the otherwise low skyline of the city. Its museums host massive collections in ostentatious buildings; public and private funds flow, with little friction, to support art collections and cultural initiatives, despite there being a soft penchant for regionalism. Around a third of Basel residents are foreign, and it’s worth highlighting the strong international artistic community.1

A few weeks after my relocation, both Diogo and I joined a seminar instructed by artist Renée Levi as part of our Master studies. Students gathered in small working groups and went about the Basel area to look at paintings. At the time, we visited Fondation Beyeler’s exhibition The Lion is Hungry [highlights of the collection, named after Henri Rousseau’s luscious painting of a lion dining on a gazelle] and Kunstmuseum Basel’s Rembrandt’s Orient — West meets East in Dutch Art of the Seventeenth Century [a showcase of Rembrandt’s love for Eastern non-European cultures], with some involuntary Picasso encounters along the way. Within our working group of multidisciplinary artists there was a shared love for painting, granted; still, we felt like such exhibitions were out of sync with our needs and mindsets: with our own condition in this place, with what it felt like to get there and how the only certainty of our situation in Switzerland during Covid was an omnipresent feeling of anxiety [we were all foreigners]. Our shared experience was the Basel-Stadt Migration Office, where I had been a few days prior for the first time; in fact, I remembered how in its lobby walls hung a large artwork by a Swiss artist2, right above the customary waiting room chairs. On Diogo’s suggestion, we all headed to the Migration Office waiting room looking for some other kind of painting.

In the office foyer, automatic glass doors give access to a large main room full of more doors and guichets with transparent acrylic panels. In Covid times, poles with straps indicated the way for visitors, and floor stickers in yellow and black marked the minimum safe distance; a security guard oscillated between the entrance and the glass doors, helping with enquiries. We stood in front of the large artwork for a while; it featured a large horizontal metallic structure pinned with translucent fabrics in different textures, often touching seated people’s heads. We traced back the artwork to the Cantonal Art Collection3, from which cantonal administrations and employees can borrow pieces to “furnish offices, meeting rooms, foyers and public spaces.”4.

What is the meaning and purpose of such a choice of artwork for this waiting room, through which every single migrant in Basel goes through, from such a large collection?

Not long after that, Diogo’s solo presentation at Spirit Shop in Lisbon [Joie de Vivre, 2021] featured a group of painting works tracing back the history of the first corporate art collection in Europe, intersecting visual elements from the early days of the artistic endeavour leading up to the collection concept and its connection to lifestyle advertisement and the life of Portuguese painter José Escada, one of the collection’s first commissions.

The relationship between corporate/bureaucratic settings and art is a seductive one; it’s about how art is used in such environments [a prop, a tool], and what is taken into consideration when making decisions about this public rendering of, for example, acquisitions of artworks by public collections. What people choose to make public, or to keep private in their offices, or even to create the waiting environments in inevitably crowded foyers of public offices. Should the works speak to the inherently bureaucratic processes awaiting them beyond the waiting room?

As Diogo writes in the exhibition text, hospitality is a regulated craft, and welcomeness is difficult to coerce. Should the artworks in such places welcome you into what may easily turn into an entangled red-tape nightmare?

Two base perspectives are presented and merged in PLEASE HOLD: there is the clear reproduction of the visitor’s, or the waiter's [the one who waits] experience, and the allusion to the speculative office-worker side. These perspectives can be traced in each room, not in opposition but in playful conversation. Here’s a mental picture: it’s an early-morning bureaucratic errand and you cleared your schedule, as this might take all day. It doesn’t matter what mess you need to solve—it might be your ID, visa application, or some unintelligible tax issue; it’s probably something you thought would be incredibly simple, but it’s been amplified by the journey and expectation of having to solve it through public services, in business days, in strict opening hours. You take a number and enter cramped and poorly-ventilated waiting rooms with which you’ll get fairly acquainted. If this is in Portugal, you know what’s up and you feel sorry for yourself even before it starts. If this is in Switzerland, you hope somebody in there speaks a bit of English and doesn’t make you feel bad about your dumb immigrant questions, but at least the waiting won’t be as bad and you might still be able to catch some sunlight outside.

The smaller room in Ausstellungsraum Klingental is a mise-en-scène of a dimly lit fever-dream waiting room.

It kindles the sleepy stages between consciousness and total obliviousness coming over the body after hours waiting, in dreadful boredom; instead of muzak there are birds singing from a screensaver-like TV display, juxtaposed with the electronic, irregular grinding of a metal suitcase [caused by internal lasers] peacefully placed on the floor which exhales a life of its own. The suitcase’s whirring is reminiscent of office shredders, as if behind some nearby office door some documents were getting destroyed away from our sight. Chairs, coat-hangers and magazine holders homage the Scandinavian design craze, and the surreal mazes on the walls act both like the scratched-over crossword puzzles in old magazines and as a visual metaphor for dead-end waiting, thwarted by time. Clocks turn without pointers; a blazer made of pebbles weighs down from the ceiling: this waiting room is punctuated with heavy, primary belongings of administrative labour. Now you hold.

But eventually, the distant, now meaningless waiting pays off and you’re invited to a new journey—a more human one—through the brighter and larger room of the exhibition.

Red retractable belt barriers methodically zig-zag through the depths of the room, forcing a unique pathway and making it clear there’s still a long way to go. An eager smiling face greets you immediately; it’s René Pulfer and Herbert Fritsch’s piece, Untitled [1983]. For 17 minutes, Fritsch [in a bowtie] smiles without interruption in what you may very easily forget is a TV screen and not a live experience. What may easily be an honest smile at the beginning soon turns into a horrible task, as minute after minute the smile becomes increasingly painful and forced; his trembling jaw and effortful gasps obliterate any trace of a genuine smile, rendering this basic courtesy ridiculous. This is the first step of shared complacency — up until now, you waited alone, but at this moment there's a shared discomfort. An appetiser of the unique, contradictory mix of maximised attention and complete dissociation stemming from boredom, from the physical experience of waiting, and the subtle dread of what’s to come. From there, every corner reminds you of the faceless and mysterious labour taking place behind closed doors and the situation’s surreal qualities.

Time is of the essence; in your slow walk alongside the red straps, you pass by large paintings of ominous clocks [are they your friend or enemy?, you can’t remember], dozens of hourglasses with different weights, other waiting beings which remained along the way [maybe they didn’t have what it takes to deal with the system]. Before reaching your destination—the desired guichet, where you get to express yourself and make your requests—you get to see all the beautiful phases of the moon against a pitch-black backdrop, reminding you of how far you’ve come and how patience is certainly a virtue.

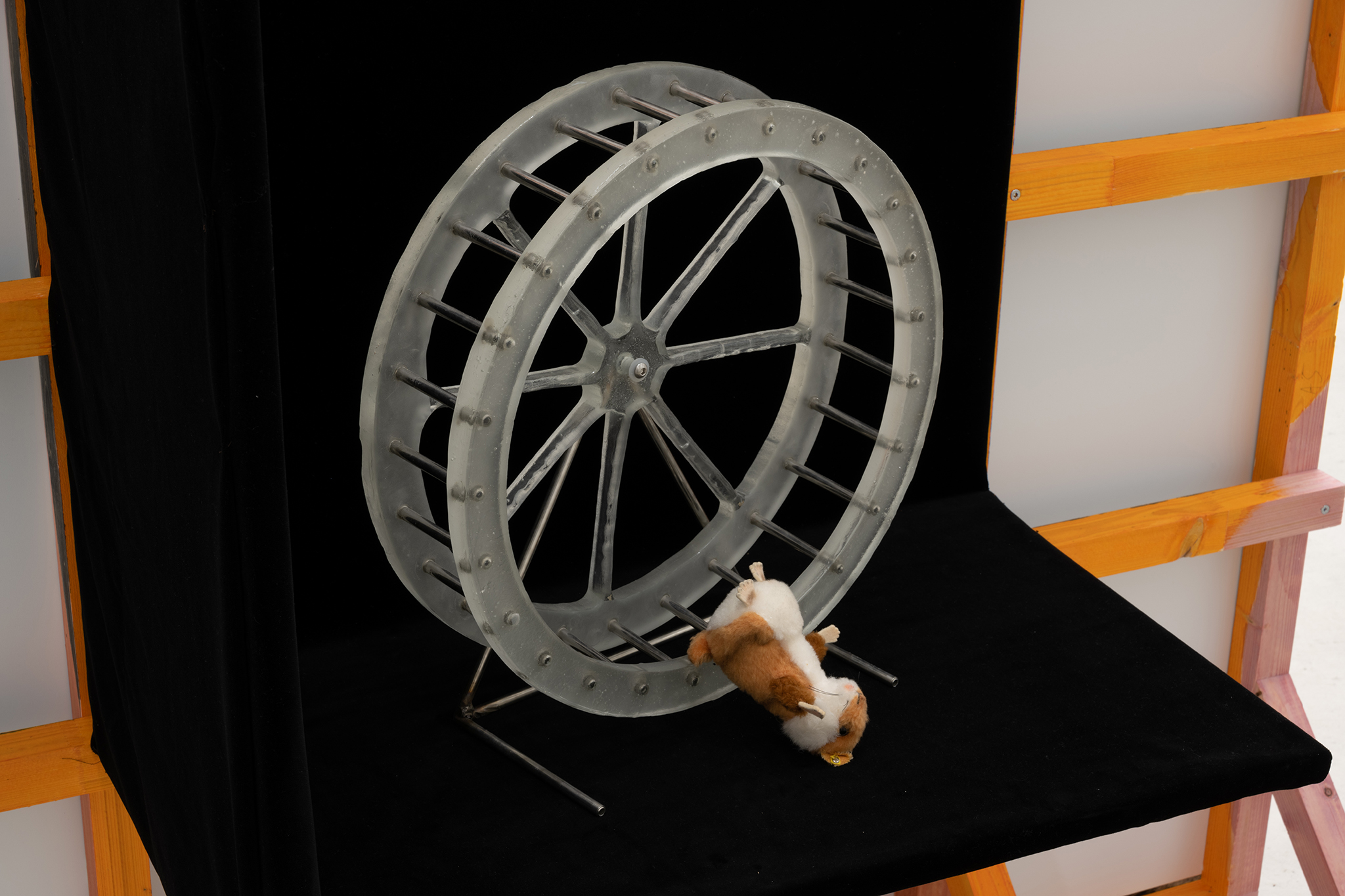

Behind the moon wall hides the final stage; you take a deep breath and carefully pass the life-size Swiss speed radar protecting it, and here you are. And turns out the final step to the journey brings out mixed feelings. Sure, the meeting place is there, and it corresponds to expectations—office-labour themed paintings [representing books, daggers, pens, hourglasses] hang on the wall, and the acrylic-panelled information counters invite you to finally solve your bureaucratic endeavour. But as you look around, overwhelmed, a glass hamster wheel and said exhausted hamster are the only ones there, in some type of sick joke played on you. No one stays indifferent to the other side of this same coin: these labour mechanisms take a toll.

PLEASE HOLD is a generous gesture: it takes the slightly-traumatic experience of Portuguese bureaucracy and transposes it into a Swiss context, one of courtesy, spotlessness, and clinical hygiene.

Many of the artists in PLEASE HOLD have experienced bureaucracy in the terms described on this text; a special note goes to Karola Dischinger, whose artistic practice stems directly from her corporate job in HR for over 10 years. The exhibition’s context is the Regionale, a yearly cross-border initiative organising art spaces and institutions from North-western Switzerland, South Baden, and Alsace. Artists from or based in the region apply to one general open-call, and the host spaces choose the artists they wish to exhibit. For Regionale 23, Diogo Pinto went through the Excel sheet comprising 632 applicants to curate PLEASE HOLD: “an exhibition made in and out of bureaucracy,” as he writes on the exhibition handout.

Kristian Suvtane Augland, Jonathan Bitterli, Karola Dischinger, Susan Fankhauser, Laura Grubenmann, Dorothee Haller, Anas Kahal, Enrico Luisoni, Matilde Martins, Anastasia Pavlou, René Pulfer & Herbert Fristch, Nicolas Sarmiento, Mirjam Spoolder and Gina Weisskopf, PLEASE HOLD (2022). Photography: Finn Curry. Courtesy Ausstellungsraum Klingental, Basel.

Mariana Tilly is an artist living between Basel and Lisbon. She holds an MFA from Institut Kunst FHNW. Currently a PhD candidate at MAKE/SENSE, FHNW Academy of Art and Design and Kunstuniversität Linz, with the project CAPACIDADES [25 de Abril / 6 de Maio]: Decoding Portuguese colonial heritages in visual representations of migration.

1Also in relation to Institute Art Gender Nature FHNW, international art school in Basel.

2Edit Oderbolz, 1966

3The piece in the collection’s online catalog: https://www.kultur.bs.ch/kulturprojekte/bildende-kunst/kunstkredit-sammlung/sammlung-online.html#search-text=edit&details=44057

4From the organisation’s website.