The Milk of Dreams — On an Earth Between Two Suns

Somewhere by the Nile, a person treads on muddy ground. In this close-up shot, we see their body merging with the soil beneath their feet, their ankles sinking into a huge puddle of wet clay. Throughout the video, sentences from Ali Cherri's Book of Mud are read both in English and Arabic. These include excerpts about the Merowe Dam, and tell the story of the origin of life on Earth. Legend has it that it has emerged from clay-bound unicellular organisms to later transmute into different species, and human beings would eventually rise as tool-makers. This cosmology encompasses Ali Cherri's video integrated in this edition of the Venice Biennale, drawing also the main narrative of The Milk of Dreams, the central pavilion of the 59th International Art Exhibition, curated by Cecilia Alemani, Chief Curator of the High Line Art, New York.

Ali Cherri, Titans. Photography: Ben Davis.

Alemani, who previously curated the Italian Pavilion in 2017, signs this edition of the Biennale with a programme that stands out for its feminist reverence, presenting an historical survey of the with relation with the body through Earth's healing practices and technological explorations. By interweaving exhibition threads that materialise as orbital, satellite narratives, this comprehensive exhibition may be read through five historiographic sections, joined by a multiplicity of artworks.

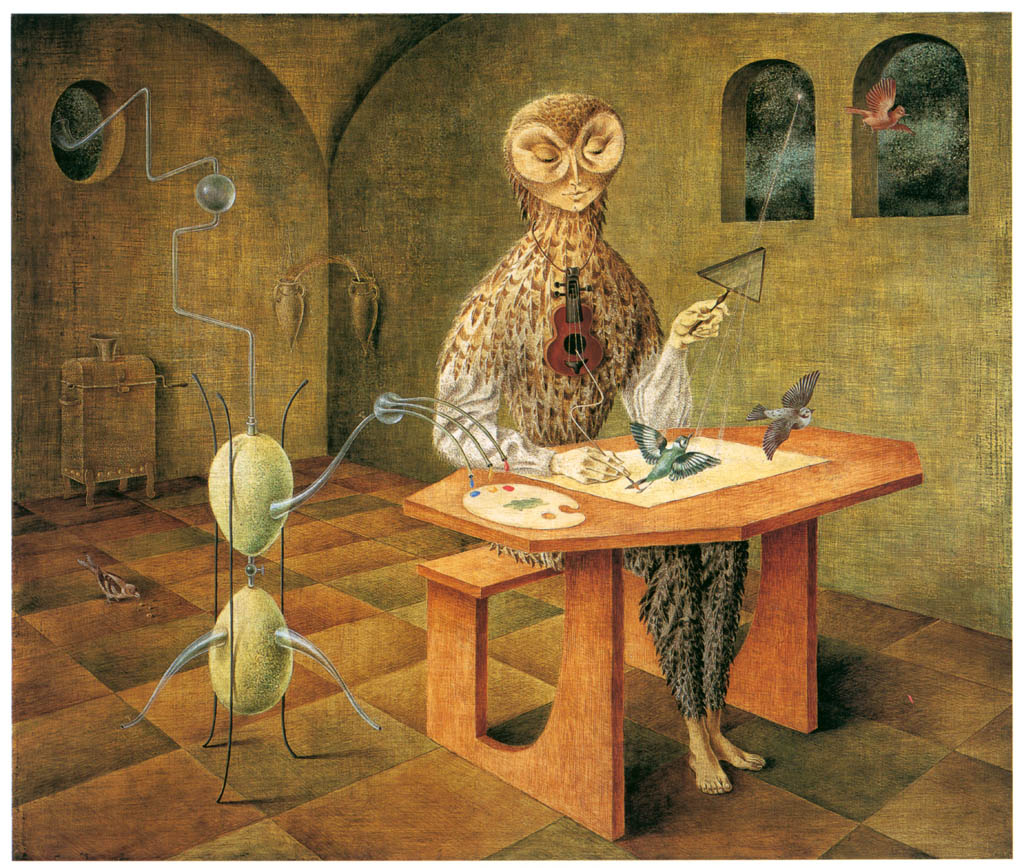

One of these sections, The Witches Cradle, is located in the Giardini Central Pavilion. It includes artworks by Surrealist female painters and avant-garde artists, drawing from themes such as the dream body and the oneiric. This section comprises works by Surrealists Eileen Agar, Leonora Carrington, Claude Cahun, Leonor Fini, Ithell Colquhoun, Lois Mailou Jones, Carol Rama, Augusta Savage, Dorothea Tanning, and Remedios Varo. Here, the power of dreams is evoked through the extensive historical research displayed, including documents, books, and films, together with consecrated paintings by the artists.

Remedios Varo, Creation of Birds (1957)

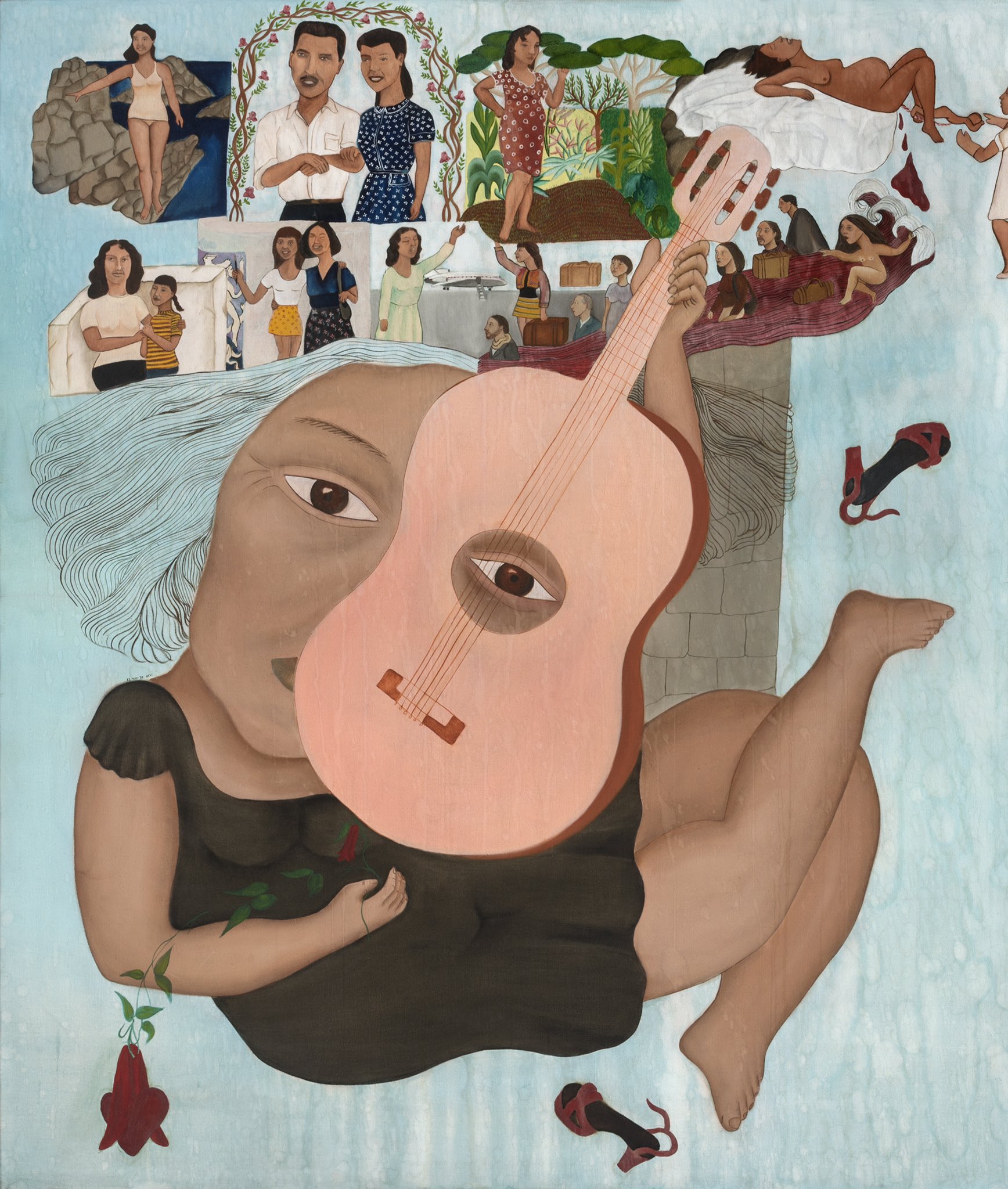

The phrase from which the main exhibition borrows its title comes from Leonora Carrington's book The Milk of Dreams, included in this section. This sentence successively appears printed over Cecilia Vicuña's painting of her mother's eyes, Bendiga Marmita, on display in the next room, circulating as the Biennale's visual identity. The powerful encounter between Carrington's phrase and Vicuña's painting — with the latter being awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement — opens a singular space where different generations and cosmologies come together to envision possible futures, at this moment of planetary unrest. The Amerindian, represented by the matriarch's wise gaze, and the Surrealist, who departing from Central Europe to the Americas, such as Varo, or others. This is an encounter made possible through the different ways of worldmaking in display — from intrauterine reproduction, to the invention of rituals or the psychedelic imagination — summoned by the various of the works presented throughout the exhibition's sections.

Corps Orbite, displaying a connection between works that expand from language and the body, pays tribute to Materializzazione del linguaggio, a 1978 concrete poetry show that was one of the first feminist exhibitions in the Biennale's history. In this section, haunted by imaginary bodies called up in seances by Eusapia Palladino and Georgiana Houghton, the formless metamorphosis of the spirit comes in the form of automatic writing, drawing, and relief, where ephemeral presences are sculpted and redefined as a sign. We can also see works by Mirella Bentivoglio, Tomaso Binga, Ilse Garnier, Giovanna Sandri, and Mary Ellen Sol, which then give rise to imaginary languages and expanded alphabets.

The sensorial lexicon and metalinguistic body expand throughout the adjacent sections, where technological and cybernetic incursions intersect artworks that pay tribute to choreographic gestures, be it through performance — Alexandra Pirici's iconic work — but also painting, or sculpture. Ulla Wiggen's paintings and prints stand out, as do Sara Enrico's concrete sculptures, and Andra Ursuta's alien bodies. These imaginary bodies are animalesque and distorted — notice Paula Rego’s room —just as ethereal and fusional — as is the case of Simone Fattal's evanescent clay sculptures, on view at the pavilion's patio, whose prophetice breath meets the garden's breeze.

In the Giardini pavilion we may also encounter another historiographical section Dedicated to the body-machine, where this junction is read through the perspective of kinetic art. Technologies of Enchantment, alludes to theoretician Silvia Federici's book Re-Enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons, and includes a number of 1960s kinetic artworks. These bridge the expanded cybernetic space in the adjoining sections with one of the axes in the Arsenale, dedicated to semiotics and technology.

Such "commons," also described as "the politics of the multitude," is likewise evoked in the first half of the Arsenale exhibition, where a significant part of the artworks presented address the communal space by representing council circles, processions, or crowds — including multiple pictorial works from the Global South, such as Portia Zvavahera. These are also the common spaces where resources such as water, ore, soil, or vegetal beings are exploited without permission, as depicted in Prabhakar Pachpute's or Rosana Paulino's paintings. In these drawings, reproductive justice is allied with the justice for the Earth, where our ancestors lie, making the substrate that nourishes the planet.

Proposing new and ancient gestures that might bring justice to the same beings that populate the former but also revisit us, The Milk of Dreams works on the numerous hauntings that have shaped contemporary society, such as the colonial past and the heteropatriarchal heritage that moulded today's bodies and spaces.

As it expands the concept of body to include the elemental, symbiotic, and technological body, its ecofeminist line of thought challenges the definition of corporeality. In doing so, it expands its transtemporality, into a posthumanism lens that is itself made out of different ancestral genealogies. How may one situate the actual body?

In one of the Arsenale's main rooms, we return to soil. Delcy Morelos's installation fills a part of the halls with dirt, including in it a mix of spices, cocoa, and hay. By calling upon the humus of the land, a nourishing humus, with the same etymology as human, this room redirects us to the foundations of present, where the essential infrastructure is the soil, the crust and matter where we come from and which lends us gravity. In a declination of what is one of the most iconic conceptual environmental art pieces —Walter De Maria's New York Earth Room — Morelos deploys the ecofeminist perspective, as she highlights the essence of the plural, fertile soils from where everything comes from. She underlines its complexity and origin by conjuring up the sensoriality and wisdom of the senses, that are themselves storytellers of the evolution of time, boasting advanced genetic grammars.

Delcy Morelos, exhibition views in 59ª La Biennale di Venezia, “The Milk of Dreams”. Photography: Roberto Marossi.

This gestational dimension expands throughout most of the exhibition, that pays tribute to the female body and its ability to generate beings and worlds, celebrating reproductive morphogenesis via multiple parallels between bodies of nature. Another of the exhibition's sections stresses this potential in an acupunctural way, by weaving perceptions of different containers together, as proposed by writer Ursula K. Le Guin. A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container pays tribute to Le Guin's theory-fiction, where she argues that civilisation has proceeded from nourishment-carrying tools, such as sacks, bags, and containers. This Arsenale gem, displayed as a round gallery, presents us with Tecla Tofano's hybrid-shaped ceramics, alongside uterine models, or Surrealist paintings and scientific illustrations on the metamorphosis of insects and plants together with Ruth Asawa's transparent wire sculptures. Walking through this gallery contained within the halls of the Arsenale is in and of itself a visceral experience where the elementality of matter and clay fuses with the internal sensuality of the reproductive system. This evokes a synaesthetic perception of the concave and convex spaces, where one is sublimated as part of a vital mould.

Ruth Asawa, vista de exposição na 59ª La Biennale di Venezia, "The Milk of Dreams". Fotografia: Roberto Marossi.

The performed body, the tool-body, and the posthuman body are also explored in the exhibition's final historical section, Seduction of the Cyborg. Here, the machinery becomes experimental, a playful game where the limits of humour and gender are challenged through daily-life improvisation and newly fantasised bionic bodies. On this section one can revisit both Dadaist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's staged photographs and Marianne Brandt and Karla Grosch's involvement in the Triadisches Ballett alongside Futurist contemporaries of theirs. The electrification of the body is found in Kiki Kogelnik's robotic schemata but also in Rebecca Horn's monumental kinetic sculpture Kiss of the Rhinoceros that etherises the room when a bolt of electricity flows through its two arms, each tipped with a rhinoceros horn, as they reach one another in an orbital motion. Another highlight is Liliane Lijn's sublime, iridescent, quasi-erotic totems.

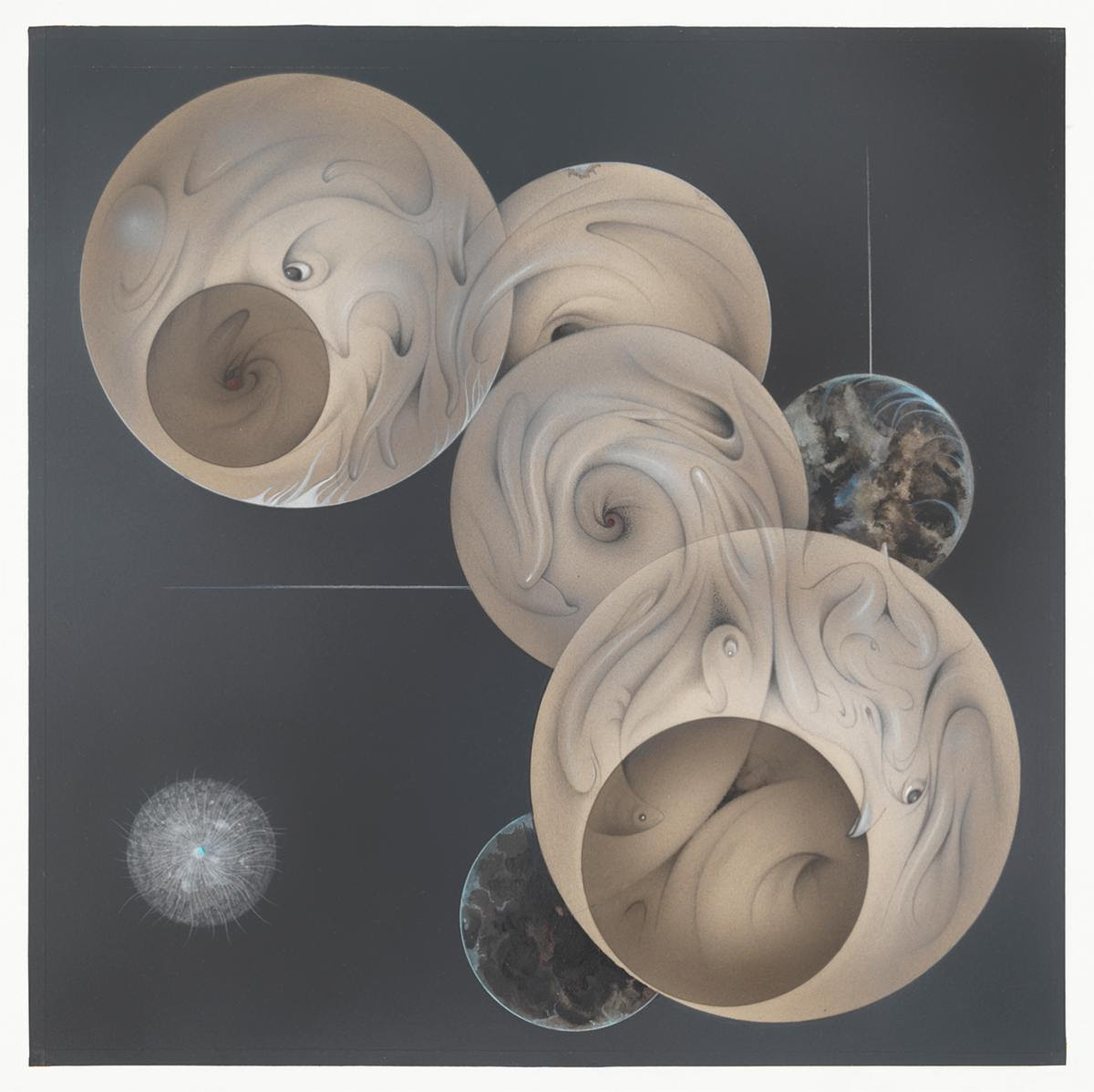

Therefrom proceeds the exhibition's final section, where the performed cyborg body is traded off for the technological, information system-bound, organ-less body, as the show ends on an excessively postmodern note that may overwhelm one's gaze. Notwithstanding Tatsuo Ikeda's marvellous drawings, Tishan Hsu's paintings and Marguerite Humeau's sculptures stand out for their evanescent digital bodies, metamorphosing into new avatars and dissolving landscapes. How many after-images have since stuck with us?

Tatsuo Ikeda, Floating Sphere (1978)

By paying tribute to female genealogies through the creative emancipation of the potential of the body, The Milk of Dreams is, without a doubt, a sensorial trip. And if, on the one hand, moving image is less present in this edition comparing to the previous —resumed tor small-scale installations in the shipyard — the presence of historical documents and ancestral gestures in the exhibition is no less audaciousy. It provides a much-needed revision of the historiographies of canonical movements that, for decades, have been carried out from the usual voices. Through a political convergence that focusses more on aesthetic proposals rather than on downright activism — à la Federici— re-enchantment takes place via the intimate space of the body and the sign, expressed in emancipatory, world-building languages and technologies. An ecofeminism that is consecrated in rituals of reinvention of the political body, that is itself gestational, creative, and irreverent. But one may also point out the return to narratives and authors— such as posthumanism and Haraway — that have saturated recent artistic discourses that cyclopically confine themselves to their own self-referentiality, while plenty of other voices go unheard. Nonetheless, Alemani's precision accomplishes its proposal by audaciously interweaving different practices and genealogies — that are indicative of how an extra year of research allowed for greater thoroughness, and provided the working conditions that enabled the exhibition to consolidate.

Indeed, this edition is one that celebrates the desinstitution of purportedly assured spaces, where national pavilions trade place and/or take on cross-border identities —with Małgorzata Mirga-Tas representing the Roma people in Poland, and the Sámi Pavilion taking over the Nordic Pavilion. Furthermore, most of this edition's prizes were awarded to diaspora artists: Sonya Boyce won the Golden Lion for her exhibition at the British Pavilion, as Simone Leigh, Zined Sedira — the first Algerian woman to represent France — or Ali Cherri, as well as Uganda's first national Pavilion, received honourable mentions.

At this moment of turmoil and celebration, as political existentialism accelerates towards fascism, and anew and insurgent, resilient indigenous voices gain ground in Latin America, imagining gestures that reconcile new and old worlds is key.

Retracing origin narratives and unpayable debts is just the beginning of a long healing process that is currently taking form.

In this world of many worlds, where the imagination is an indispensable tool of action, reconciliation with the plurisensorialities and the multitudinous beings that have existed and are to come is essential. For only through this process of narrative reinscription, taking on the corporeality of infrastructure on an Earth between two fates — or two suns— can we ponder whether reconciliation is indeed possible.

Margarida Mendes is a curator and investigator. Her research — with a focus in the environmental humanities, experimental film and sound art — exploring the dynamic transformations of the environment and it's impact in social structures and in the field of cultural production. Integrated the curatiorial team of the 11th Gwangju Biennale "The 8th Climate (What Does Art Do?)", 4th Istanbul Design Biennial "A School of Schools", and 11th Liverpool Biennale "The Stomach and the Port". Consultant of environmental ONGs that work on the mining on the deep ocean, and worked with various educational platforms like escuelita, an unformal school in Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo - CA2M, Madrid (2017); The project space The Barber Shop in Lisbon, dedicated to transdiciplinary research (2009-16); and the curatorial research platform on ecology The World In Which We Occur/Matter in Flux (2014-18). Margarida Mendes holds a PhD in the Centre for Research Architecture, Visual Cultures Department, Goldsmiths University of London.

Translation: Diogo Montenegro, edited by the author.

Cecilia Vicuña, Bendiga Mamita.

Cover image: Cecilia Vicuña, exhibition view 59ª La Biennale di Venezia, "The Milk of Dreams" Photography: Marco Cappelletti.