Federico Herrero: Tactiles

Breathing Borders

There is something energizing in Federico Herrero’s interpretation of Kunsthalle Lissabon’s double-roomed white-cube basement.

As you walk down the stairs, colourful rounded rectangular shapes—painted directly on the walls—greet you with the confident innocence of youth. They seem to be moving upwards along the surfaces in groupings, reaching the ceiling in patches, like joyous bubbles or balloons ready to burst into some implied open skies. Coming in lovely bonbon nuances of greens and yellows, with orange, pink, and blue highlights, they playfully contrast with the bleached coldness of the walls and lights. On the floor, grey concrete sculptures in the shape of triangular prisms gather in two square formations. Instinctively, one is reminded of little pointy mountains and/or ranges of pine trees, especially when seeing them from the stairs’ higher stance. Subtle, the soft pastel grey of the concrete they are made of is underlined here and there at the basis of the shapes by a thick stroke of running green.

In Costa Rica, where he lives and works, Herrero divides his time between urban and jungle environments, and his visual language is largely informed by experiencing both, and therefore contemplating the limits of each. About this work, he speaks of the liminal space born from the tidal encounters between the ocean and the jungle, which is mediated by the sands of the beach, morphing with time and every back-and-forth movement between the waters and the prolific expansion of the tropical forests. But, without even knowing the artist’s life, the room offers the viewer a minimalist bright landscape where cues are given by concrete and colour blocks in lieu of hills, valleys, fields, and rainforests — is that a ribbon of ocean spotted in the horizon? And there, is that a meadow, or perhaps a flower bed? In any case, Herrero’s palette draws from sherbets, lush greens, and sunny blues—evoking in a way the practice of a modern painter of the tropical outdoors.

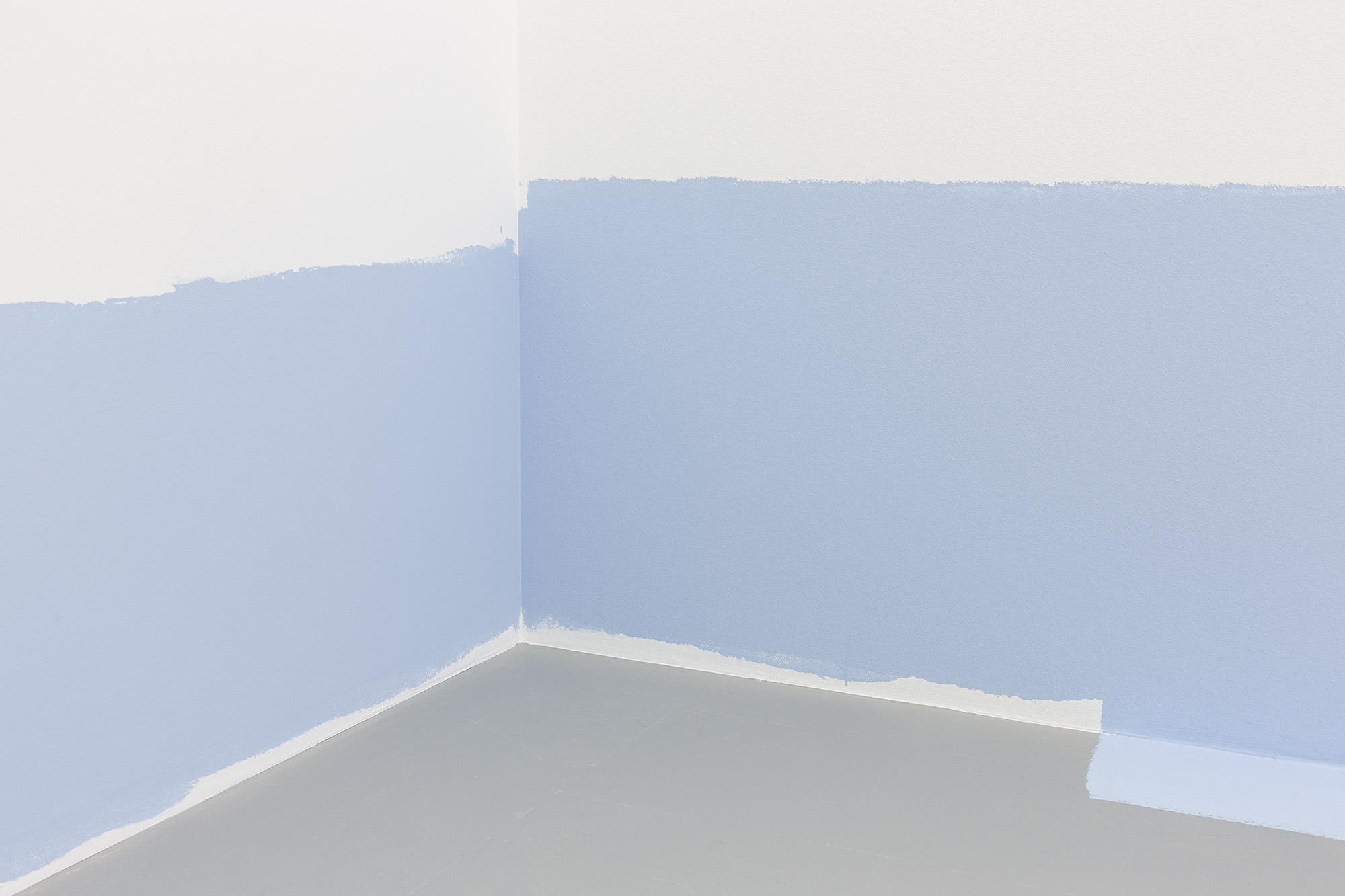

The next room, smaller and more contained, is obstructed by several concrete and wood table sculptures of varying height that the viewer needs to contour. All depart from the rectangular shape, either as a concrete slab or a plank, to which the artist has added trestles, as you would do to build a table, and/or partitions, as in an out-of-centre ping-pong table. There is something about the texture and colour of the concrete that somehow manages to appear velvety. This palpable quality is comforted by the title of the exhibition, Tactiles, which seems to tease the viewer into running their fingertips on the sculptures as if they were made of plush upholstery. Surrounding the sculpture-isles is the colour blue — a slightly grey pastel blue on par with the soft grey of the concrete sculptures — which covers all of the lower parts of the surrounding walls, as if the room itself was an island. And if it were an island, it would not be wild and virgin, but rather inhabited by simple brutalist constructions made of cementing material.

More than anything, Herrero’s work is to be understood physically, as it reintroduces a sensory approach of apprehending the world to adult souls who have long forgotten the kinaesthetic joys of kindergarten. However, if the work appears naive and playful by certain aspects, it also delivers a certain amount of pressure, if only because it feels contradictory to experience nature via concrete. Or also because one could think of how weeds, flowers, and even trees always manage to grow — in a tropical climate they certainly do — through some cracks and crevices in the bitumen. Which is also a reminder that nature always finds a way, with or without humans, or despite humans, who might just be discarded. At least some theories suggest it in these times of environmental concerns, with especially worrisome changes of temperature and rising sea levels threatening to overflow islands and lands.

But the necessity to heed Earth’s message aside, this work is inviting us to be attentive to the physical incarnations of boundaries and borders — incarnated by partitions, membrane-like shapes, and horizons. Our bodies can realise the realities of Earth’s gravity and tidal nature, but also by extension the idea of psychological boundaries and the implications of co-existence at large.

The forces that push and pull oceans and shores or those that exist between wilderness and constructed environments or those at stake on a border between two countries or sea territories could all be manifestations of how any element in the universe, a particle even, occupies space—in co-existence with all the other elements, or particles, in the universe.

Co-living or co-being creates energy. And so border zones between landscapes; political, economic, social, and cultural divisions and overlaps; ideological commonalities and differences—anything material and immaterial that contains contrast generates an energetic intersectional territory. And that liminal territory, itself in constant movement, is, in other words, alive.

A limit is not just an end: it is a living zone, in a constant fluid state, not unlike or just exactly as the universe we live in.

Proofreading by Diogo Montenegro.

Cristina Sanchez-Kozyreva is an art critic, curator and writer. She is a regular international contributor to art publications such as Artforum, Frieze, Hyperallergic, and other publications including the South China Morning Post. She was the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Hong Kong-based independent art magazine Pipeline that ran print editions form 2011 to 2016 where she curated thematic issues with artists, curators and other art contributors. She has a Masters degree in International Prospective from Paris V University. She is the editor-in-chief of Curtain Magazine.

Federico Herrero, Tactiles. Exhibition views. Kunsthalle Lissabon, Lisboa. Photography: Bruno Lopes. Cortesy of the artist and Kunsthalle Lissabon.