MATTIN: Expanding Concert (Lisboa 2019-2023)

About the first performance of Mattin's Expanding Concert (2019–2023), on 6th December 2019, 7 p.m., at Galeria da Boavista.

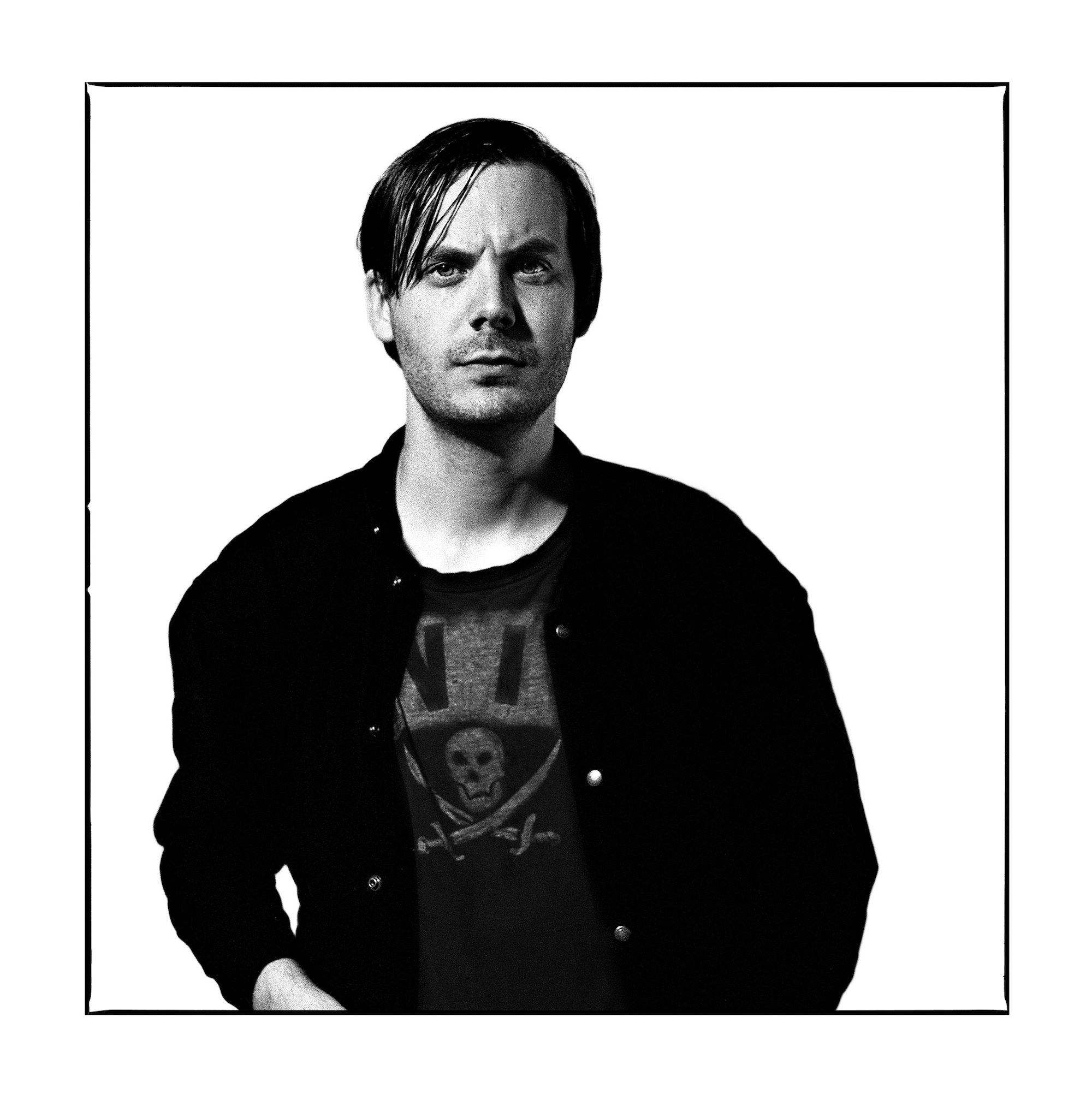

"Alguna pregunta?" [Any questions?] Thus began the first of five Expanding Concert (2019–2023) performances by Mattin, the Bilbao-born artist currently living in Berlin. His is a versatile work, mediated by noise and improvisation. Noise and improvisation are the main ingredients of his works, which often tackle topics related to phenomena such as gentrification and individual or collective alienation in a subjective, intangible manner.

After a few minutes of uneasiness-induced silence and shy glances, somebody asked the artist the first question: "How old are you?" Mattin was standing, leaning against one of delimiting walls of the rectangular, approximately 100-square metre large space at Galeria da Boavista. Around him, leaning against the wall as well, was the expectant audience, curious to see how the performance would unfold. Mattin slightly turned his body towards the voice he had just heard, and replied: "Forty-two." A few minutes later, with his eyes on his phone, the artist asked a second question: "Don't you ever get the feeling we increasingly have to sell ourselves?" After a few silent seconds, somebody reacted: "Yes, to promote what we do… I wonder, could we manage without social media today? Could we possibly go back?"

“There's no going back," Mattin replies.

Mattin was eager to grasp the personality of this audience. The questions, the answers, the dialogue, and the attitude of those present were the only things that mattered to him. For the first 20 minutes, silence was the protagonist of this gathering, which was rarely interrupted by a question or comment from the artist or the audience. A silence which everybody wanted to break, but which nobody had the guts to. So, I started to imagine, what would it be like if Mattin's Expanding Concert took place in a South-American country? Brazil, for example. Or right here next door? In Spain, for example. What would the audience's reaction be like? Would they be more inquisitive? Would they interact more? Or would they be leaning against the wall, just like us, smiling shyly and waiting for something to happen?

Suddenly, somebody suggested we played some music, perhaps believing it would be a nice way to break the ice, to clear up that shyness-induced silence. But the artist did not agree, and foreboded the uneasy subject he had been meaning to approach by asking a question: “What do you think this neighbourhood will look like in four years’ time?" Now several people from the audience finally began exchanging ideas: “More people!"; “More tourists. Fewer locals"; “Things will be more expensive"; “People are going to start moving to the countryside"; “Of course, it's a calmer, inexpensive place with greater quality of life; each resident can have their own kitchen garden, connect with nature…"

It seems this was an interesting subject for most of the audience. It was the subject that bothered those who live in Lisbon and have witnessed a process of sudden gentrification, where spaces are designed for visitors and not for locals, the latter barely being able to pay the city's high rents. People who have always lived in the city are growing tired and starting to move to the countryside. Following my train of thought, I asked a question: “But after all, if the countryside is that good, why don't we live there? What is it that attracts us in the city?" Someone replied: “Commerce. Historically, commerce is what makes the city. It's a place where you make money." "And that's it?!" somebody protests. “Yes, we're no longer citizens: we're consumers." Then, diverging opinions. “No. It's not just about commerce. It's also about the possibilities that cities offer, such as culture, socialising, and the exchange of experiences. The thing is that Lisbon has become a product. A product for tourists." Silence. A moment when Mattin took the opportunity to make a provocative request: “I have a suggestion: if you think that things will get better in four years' time, please stay here. If you think they'll get worse, come with me. I think it will get worse."

Some people moved away from the wall and started following the artist, who was heading toward a smaller gallery space. The pessimists' group was formed—a group which I was part of and which was curiously smaller than the optimists'. The conversation took on a political tone. The collapse of Europe was foretold; the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity were assertively claimed to be bound to expire—and Europe would not survive without them. We discussed the instability of our world and its lack of foundations. We criticised Portugal, a country which is not producing any knowledge or culture, and that only cares about producing tourist-ready goods—"pastéis de nata," [custard pies] as somebody suggests. We agreed that we are at a turning point, that the current model is unsustainable, and that something is bound to happen. We were five pessimists speculating about the world's collapse. “Será que somos la última generación de artistas no artificiales? Somos los últimos romanticos?” [Are we the last generation of non-artificial artists? Are we the last romantics?] Mattin asked.

That was when somebody entered the room and offered beer to the audience. We celebrated the appearance of something that drew us away from catastrophic thoughts, and headed toward the optimist group, the members of which, curiously, were effusively chatting. Perhaps because they did not have the artist's mediation.

They were easy, delighted at the music somebody's phone was playing. They were all chatting, singing, laughing.

50 minutes later, easiness began taking hold of the room. The artist himself no longer had a voice amidst all that noise. Sometimes, there would be a moment of silence, as though something suddenly reminded the audience that this was an "artistic action," but informality had already established itself. After dimming down the uncomfortably strong lighting, somebody suggested it would be a good time to listen to some music, and incited the participants to sing songs from their countries of origin (about half the audience was not of Portuguese nationality). Most picked up their phones and started playing songs that in some way represented the various cultures and places present. I remember the first one was a song from Albania, Oj zogo jelek me vija; then, somebody started singing Ode to Joy in German. Mattin picked a Basque song for everybody to listen to and sing together. We listened to some Portuguese classics too, among which Fausto Bordalo Dias' Navegar, Navegar. Perhaps that was what all of us in there longed for: to navigate. To go with no set destination. To find another place.

Definitely, Lisbon seemed to be an uncomfortable city for most of those present. A city, somebody remarked, that had sold its soul to tourists.

What was the intention of this performance, which encouraged an unusual get-together of people who did not know each other but were aware they had to interact with one another in order for all of this to make sense? Maybe Mattin wanted to test people's (extant) capacity for "live" communication with each other. Maybe he wanted to test if they are still capable of sharing ideas, emotions, and concerns. Perhaps he wanted to prove that, though we live in a world levelled by social media and by an avalanche of excessive, insignificant, non-hierarchised images mediated by the internet, we still have the ability to exteriorise our emotions and ideas in the presence of others. This was something that is being annihilated by mass media, by entertainment-provided images, which saturate and supress our senses and emotions, thus "freeing" the viewer from their responsibility to reflect and imagine. As Franco "Bifo" Berardi stated, "Sensitivity is at stake in the current transformation of language, in the current transformation of communication, because the communication cycle of our times, the age of digital technology, is increasingly transforming within the connection and transference of digital signs. How can a sensitive being distinguish the ambiguous meaning of a non-verbal sign in a digital environment?”[1]

Nowadays, it seems that we feel by using only one of our senses: our sight. Mattin collectively activated hearing, smell, touch, and even taste. They are fundamental to understand the world, and are required for living a full life.

“We need a new harmony dissociated from the millions of nervous stimuli that we receive and to which we are instigated to respond every day, in order to rediscover our social body, and the path amidst the fog of ambiguity.”[2]

What is the social body? How does it manifest itself in the age of digital technology?

Maybe it was the answer to these questions that Mattin sought to find as he set out for this set of five performances titled Expanding Concert (2019-2023).

With no audience, this performance could not exist; it could not take place. We do not refer to performance in the same way we did in the late 20th century, when it took the human body to unconceivable limits. Performance is also not about the expressive body, the matrix of performing arts, such as theatre. Nor is performance about the body, which is simultaneously subject and work of the performance, where the artist is its source material, and the work they present to others is exhausted in the fleeting instant of its very emergence. They speak about a performance where matter is the encounter and exchange of words, silences, emotions, expressions, and ideas.

What questions would Mattin and the audience ask now, after a spring marked by a pandemic which occasioned more than two months of lockdown? Let us find out during the next and second edition of Mattin's Expanding Concert, in 2020.

Bárbara Silva is an architect, independent curator, and publisher. She is a professor at the Department of Architecture at Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (DA/UAL) and at the Department of Architecture of the University of Coimbra. From 2013 to 2016, she curated the Architectural Season at Galeria da Boavista, in Lisbon, a yearly six-month-long event comprising exhibitions, conferences, and debates on architecture. She has recently edited Jorge Figueira's Arquitectanic, os dias da Troika (2016), as well as Luís Santiago Baptista's Modern Masterpieces Revisited (2016). She is the director of the Architecture Gallery — NOTE, in Lisbon, since 2018.

Translation PT-EN: Diogo Montenegro.

[1] Conference by Franco "Bifo" Berardi, Poetry and Chaos, at Teatro do Bairro, Lisbon, 12 October 2019.

[2] Idem.