The Grotto

The grotto is a collective project currently taking place in the basement of Galeria Quadrado Azul, Lisbon.

Its intention is to create community among the gallery, a group of artists, their practices, and the visitors. Its aims are ambitious ones, concealed as they are in the gallery's basement—or more exactly in the darkness of the grotto that has been built down there. Halfway between the natural and the artificial, The grotto was created using found objects from the streets, surplus materials from works of friends, and materials that would end up being recycled or had been discarded. The idea of creating a new device to produce, reflect upon, and accommodate contemporary art was not restricted to the non-rationality or non-architecture of it, which seems enough to me to trigger some thoughts about and discuss what we do and how we largely act under the same type of artificial lighting, in orthogonal spaces, with the latter's rational impositions upon the works. Above all, The grotto raises a number of questions not only about those who produce or present their works in it but also about those who view them, among whom it generates a certain harmony. The visitor becomes an active spectator as they edit what they see / look for using their phones' flashlights; the relative danger inherent in the space affects the way we walk and the direction we look in—looking down (animal stance), looking forward (human stance), which is able to intensify sensations and produce appropriate conditions for new epistemologies. This community between creator and viewer extends to the oxygen they share, ephemerally crystallising into spontaneous conversations—something of a singular nature which often comes about when the flashlights are out and debate takes place in the darkness, thus transporting the work therefrom into the real.

Another formal aspect of the project is its being open on Saturday afternoons, as it allows for welcoming audiences of various ages, as well as families, which enjoy the possibility of taking part in an artistic event with no family restrictions, in a symbiosis of experience and reflection shared by all participants. Children (pre)dominate inside the grotto, sometimes not even caring about what is happening in it, just to later blurt in ingenuous fashion something quite deep about what we are trying to do there. Only seemingly a fait-divers, this is a crucial question that echoes some thoughts about children's insightfulness and an interest in considering how children, even before learning to read, can offer us something outside the grid of language.

The themes implicit in The grotto are not only formal ones, as a project (reception mode, opening and closing hours, rhythm, and so on), nor are they confined to the aesthetics of its protuberant, rough walls. The questions in it arise through the dark cloud that makes us aware of the human footprint upon that subterranean crust, which, if artificial, tells us we need to create new forms of empathy among us, and especially between humans and nature—how nice would it be that it sufficed to say among us, as though it repaired such a terrible separation—thus establishing horizontality between humans and nature. As such, we wanted to create a temporal arc between rock and contemporary art. Rock paintings contain a set of values we believe to be essential for contemporary art, for they proceeded from a collective act potentially acknowledged as a rite of passage or as a passage of meanings and ways of being. Rock paintings were communitarian ones, and they were made at a time when there was gender parity. In their condition of hunter-gatherers, the makers had a relationship of worship to natural phenomena, and a horizontal one with nature. The most beautiful image that rock art carries along is the enigma of it, which still persists, as it poses a challenge to our voracity for wanting to rationally understand all. Some studies argue that the first paintings proceeded from the expansion of human consciousness—consciousness being a field that, while encompassing rationality, goes beyond it. This is an extremely important image to understand the potential of art to not only interfere in other areas of knowledge but also create synergies, thus freeing scientific discourse from its restraints and generating new analogies apprehended beyond language (incorporating, digesting something between stomach and brain) by sharing and acting sympoetically (Donna Haraway). The idea of art as a broadening of consciousness readily draws upon the idea of contemporary art as an event—something that takes place in front of our eyes and forces us to jump into the future—thus producing new epistemologies, transforming our organs, and creating sensations for something new that asserts itself against "presentism," the colonisation of the future, or any other established hierarchies of class, gender, or race, which, as social and political problems, relentlessly resonate in the field of art.

The extension of human consciousness is the image of the prolific work carried out by the arts in the fourth industrial revolution, which, given the elasticity of it, allows us to coexist in the dichotomy between this mode of literacy and a relationship with nature. Art is the soft matter that gathers ideas, objects, and seemingly dissimilar or opposite living structures, evolving symbiotically or osmotically and nourishing a number of living structures. In this sense, art prepares our bodies to cope with immeasurable heterogeny and a breakneck speed of events. At the same time, art draws our attention to the little things, especially the values of the natural world, laying a path for us to rediscover ancestral non-western knowledges currently suffering under the oppression of the rational in daily life. In its innate fluidity and openness to the other (human or not), art operates a revolution of bodies without which one is not to expect any transformation of ideas and behaviours whatsoever.

The grotto results from a dialogue with Manuel Ulisses and Gustavo Carneiro, and manifests an understanding and acceptance of my problems and desires as an artist. It is important to highlight an understanding of my activity beyond this historical limitation that persists in restricting the activity of artists to the studio-gallery and studio-institution axes, thus denying contemporary artists a set of possibilities for it lacks the required framework, from the point of view of representation, critique, and subsistence—the result of a system that preserves an undeniable imparity between those who choose (curators, museum directors, trustees, collectors, critics, and journalists) and those who are chosen (artists).

An ever-changing collective work of art requires huge elasticity and generosity from the artists producing it. The biggest challenge is that each artist become a means and not an end. The grotto is not an exhibition space, but rather a collective work; notwithstanding any possible flaws, we have attempted to arrive at the point where we regard an ongoing work as a play of forces, not of forms. It is in such communitarian sense that I will describe the contributions of each artist.

The venue was created with Vasco Costa and Filipe Feijão, who have made works that were an inspiration for this project and with whom I had worked in other communitarian projects (Projecto Morro, in a biological garden in Costa da Caparica; Quindici Giorni d’Arte Collettive, at Cripta 747, Torino; Dromoshere, at Galeria Collicaligreggi, Catania; and now Osmose, at Quinta do Quetzal, Vidigueira). The walls resulted from their sculptural knowledge, their sensibility, and their intensity. For three weeks, we suffered physically and mentally so as to overcome budget and time constraints. I remember Vasco's van parked on the street with a giant three-phase generator running inside; the pub owner who was an electrician and lent us a hand; the three of us living in the same house and experiencing the grotto according to the different phases of its setting up: gazing at the café where we would have breakfast and transforming its orthogonal space with little pieces of wood, and then with polystyrene, and so on. They are the only reason we were able to make The grotto. I remember seeing the walls covered in a layer of projected plaster (the floor, in aqueous resin) leaking a lot of water, and then Antónia Labareda coming in from Caldas Rainha in the middle of the night with an industrial heater. My brother Pedro, always there.

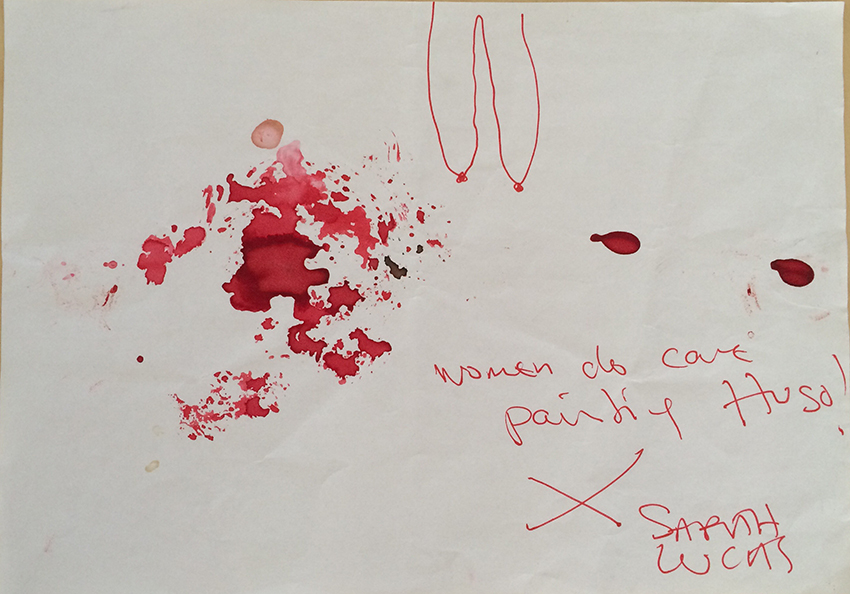

Intended as a feminist project, it is quite odd that three men built the place where the works would develop. It would have been futile to create and transform this project if not in close dialogue with Ana Vaz, Sarah Lucas, Katharina Höglinger, and Mathilde Rosier. Ana Vaz was the first visible voice, proving of invaluable help in tailoring the venue to show films (bearing in mind Benjamin Valenza's idea, who had already suggested we carried out Robert Smithson's project Cinema Cavern, which has never been carried out, in a Sicilian grotto which I never materialised). Ana Vaz presented her film A idade da pedra at the opening, with Vasco Costa and Filipe Feijão relinquishing the authorship of it. This altruistic gesture signals the passage from an end to a means. It now seems quite easy to show a film on those walls, but the texture and protuberances on them edit what we see; because of that, I have the greatest respect for Ana's generosity. As regards her film, a mimetic relationship was established among a stone quarry in Brasília, a dystopian 3D rendering of it, and this place.

Katharina Höglinger's first physical intervention took on a feminist perspective that opted to keep clear of the capitalist or controlling logic underlying the seizing of the space, transforming it instead to better foster and create community. Her intervention with the painting of a reclining woman and concentric shapes helped the following artists act inside the venue, thus breaking the potential spell of the blank piece of paper or the immaculate work the grotto imposes upon those who work in it. At the same time, Höglinger made the space cosier with her paintings on cushions, which we later used in Sílvia das Fadas's Luz, Clarão, Fulgor — Augúrios para um Enquadramento Não Hierárquico e Venturoso. This process film was presented in two sessions to an audience of 17 people each. Some film excerpts were presented using two contiguous 16 mm projectors as Sílvia intervened upon the projections with written words, subsequently reading a text of hers and playing pä music. Her work was circularly enclosed within the grotto by the intensity of communion and the testimony of the creative act taking place in front of us in the film, the content of which looks into what is left of Alentejo's anarchist communities and to the new expressions of such history of resistance.

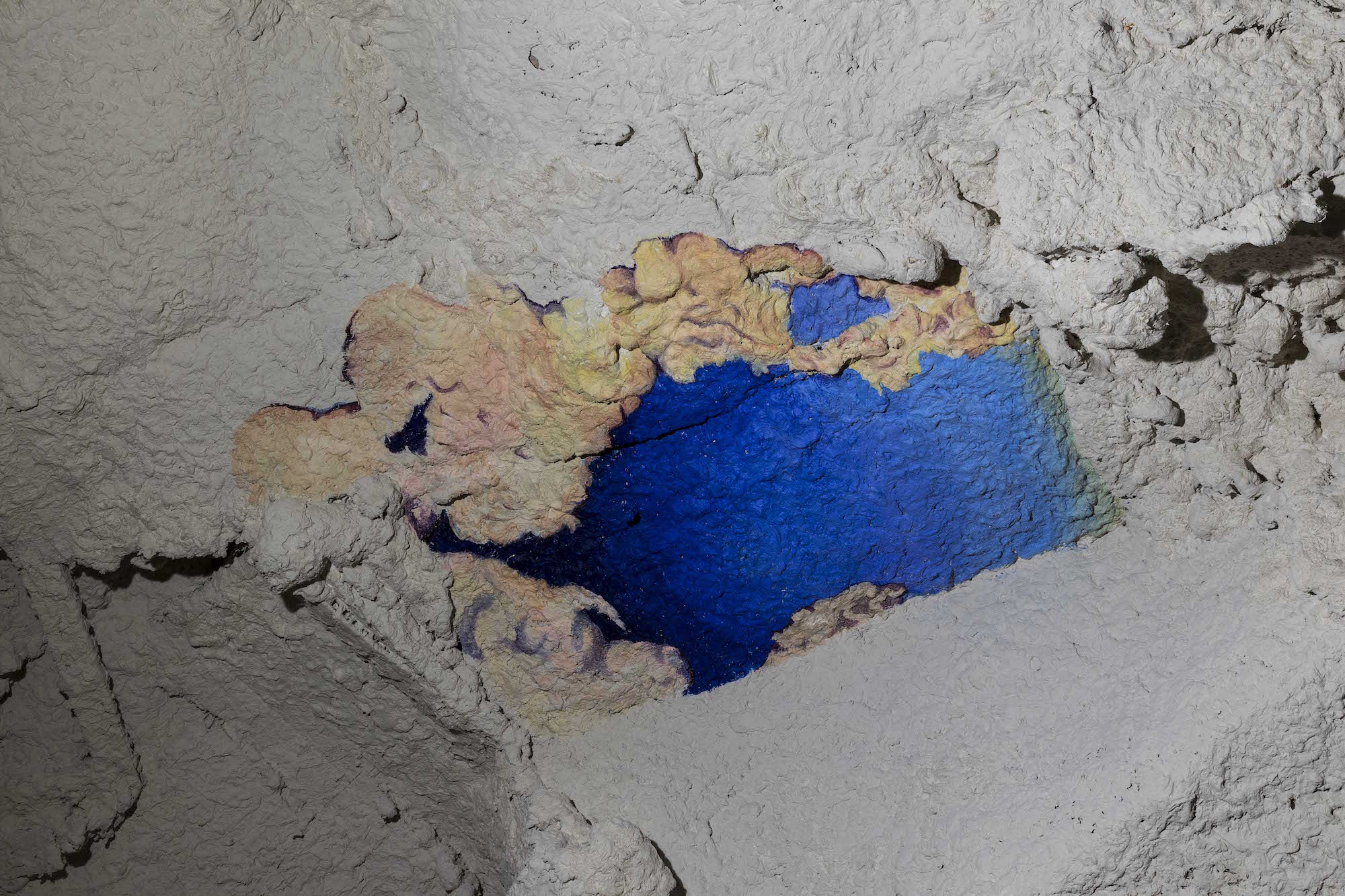

Musa paradisiaca brought in a set of wooden sculptures made in collaboration with São Toméan sculptor Tomé Coelho. The objects in the grotto were activated by a sound piece titled Comissão das Almas, which was also made in collaboration, this time with Henry Cronje, João Mota, Maria Filomena Molder, and Nicolau Lavres. The testimonies in it, focusing on the inability to be other or to fully understand the other, reckoned the artist as a result of many voices—for all art is collective, that is what I believe. At the same time, the sound piece allowed one more time to be with the objects, thus affecting them and becoming the place of projection of what one was hearing, no matter how dissimilar the two works were. Bringing objects into the grotto allowed Beatriz Marquilhas, who was extremely helpful in this project, to exalt ideas of female representation in the Palaeolithic as self-representation, taking LeRoy McDermott's text Self-Representation in Upper Paleolithic Female Figurines as a starting point. Something resembling a natural evolution took place between this idea of self-representation and Titania Seidl's intervention, whose paintings displayed Baroque-painting textiles rendered as quasi-sculptural, autonomous objects, thus suspending their main function—that of covering female nudity. The niches painted by Seidl on the gallery's ceiling are windows that open the grotto out into an imaginary exterior. As soon as we saw the horizontally made, abstract markings-ridden preparatory sketches in watercolour, we realised these would be difficult works; yet, the challenges posed by the walls' roughness and by gravity were overcome by how they became a positive force for her paintings. These four painted skies established a harmonious relationship with Höglinger's work, which enhanced the whole of the grotto—both what had been painted and what had not been intervened on.

The first person that approached me to make an intervention in The grotto was Rubenne Palma Dias. He did it as he helped us finish the space, in a race against time, by putting underlayment and applying resin coating on the floor. An initial intention of projecting Guido Brignone's film Maciste all inferno (1925) to create a mise-en-abyme in The grotto gave way to a journey to the early days of cinema, especially to Segundo de Chomón's (1871–1929) films. The grotto was then interpreted as a filming location. Part of this entailed inviting CRAMOL—the first feminist choral group—to sing in The grotto. Their voices were mastered by the space, and honestly I had never felt as magical, prejudice-overcoming a moment as the one we experienced there. CRAMOL's charm populated Rubenne Palma Dias and Jorge das Neves's film, which, although in digital format, accumulated different intensities that transported us into the magical power of images and into their extralinguistic scope.

Sophie Nys put an advertisement basket and a 14-button Entryphone, both in stainless steel, at the entrance of the grotto. In the basket, Tee Corinne's book Cunt Colouring Book established a clear relationship with The grotto. The bells, on the other hand, referred to 14 historical figures that had taken shelter in caves throughout history, the most famous of which possibly being Odysseus, who replied "Nobody" when Cyclops asked his name so as to escape death. "Nobody" was the figure created in the 15th century to take the blame for any domestic incident. "Nobody" is the fragile, elastic figure that takes all the blame for the brutal neoliberal economic evolution felt at the time in Lisbon—one all the more highlighted via the 14 prints of a wall hole made by pulling a bell out.

Jannis Varelas's intervention extolled Art Brut and rescued those who, although excluded from society, can offer us images capable of mediating the world sensibly. Varelas accepted the challenge to take more space up, and created, for the first time, a tangible dialogue between one work and another by means of overlaps or by contaminating his work in relation to others.

Both the idea of juxtaposing a work aware of the rationality inherent in Corbusier's Unité d’Habitation, Marseille, with the grotto's non-architecture and the intervention's invisibility, which required a non-retinal relationship with the work, thus sublimating other senses, set the theme for Daniela Grabosch's invitation, who, together with Anna Thomas, designed a fragrance for the grotto's walls. The grotto is also a place of synergies; in addition to this invitation, another project was conceived for the Off.site Project online curatorial platform, onto which images of all interventions alongside texts by others artists, online images, and a set of 3D VR scans were uploaded, thus placing such models side-by-side with urban landscapes and construction sites.

Elise Lammer, Julie Monot, and Lucien Monot's performance BECOMING DOG highlights The grotto's interest in exploring new forms of empathy. The performance related a woman's transformation into a dog through a reading of a text about Virginia Woolf, Kafka, and Snoop Dogg, as she mimicked the positions of the dog beside her. This performance also marked a filming period when a woman's transformation into a dog became the genesis of a collective film-opera titled Theodora ou o progresso, which has taken the grotto to the outside world, now relating to a new heteroclite group of artists.

In February, Georg Frauenschuh came to The grotto to make an intervention with a view to going beyond the aesthetic typology of the pictorial interventions on the walls, which we promptly identified after discussion—the roughness of the walls metabolises and gathers all. His intervention was carried out as a middle act, no opening scheduled; visitors will be able to see it as soon as the Directorate-General of Health allows the venue to reopen. Deploying a pictorial language more closely focused on the history of painting than on the implicit concerns presented at the beginning of this text entails reckoning The grotto as a tentacular, absorbing figure that generates mutualism and infects back the works made by those who have taken part in it (to the extent of their capacity or intentionality)

Outside this extensive listing, there are several other artists who, although they have not been mentioned, have provided guidance and inspired this project. It remains for me to thank João Ferro Martins, who both helped a number of artists mount their works and photographed the latter brilliantly, and Nuno Barroso, who assisted us in ways that go much beyond mere technical support—ways in which one's sensibility and artwork is used to the benefit of another's—as well as Andreia Santana, who, for example in helping and supporting Katharina Höglinger and in providing crucial assistance to Sophie Nys's project, committed to The grotto as though it was hers, in both an empathic and intellectually rigorous manner. Lastly, I would also like to thank Adrien Missika, who, with his Belo Campo project at Galeria Francisco Fino, gave me the possibility to bring The grotto into the basement of Galeria Quadrado Azul.

Hugo Canoilas (Lisboa, 1977) lives and works between Lisbon and Vienna. Graduated in Visual Arts by Escola Superior de Artes e Design Caldas da Rainha and Master in Painting at the Royal College of Art in London. Develops since 2019 the colective project The Grotto, in the basement of Quadrado Azul Gallery, in Lisbon. Selected solo exhibitions are Buyoant, Martin Janda Gallery (Vienna, AU, 2021); Pólipos cnidários reparados pelo olhar do observador, Museu de Serralves (Porto, PT, 2020); On the extremes of Good and evil, Mumok (Vienna, AU, 2020); Antes do Início e Depois do Fim: Júlio Pomar e Hugo Canoilas, Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar, (Lisbon, PT, 2019); Debaixo do Vulcão, Sonae Art Cycles, MNAC (Lisbon, PT, 2016); Lava Grotto, A.V. Festival (Gateshead, UK, 2016); Pássaros do Paraíso, XXX São Paulo Biennal (BR, 2012). Selected group exhibitions are: Carnivalesca- what painting might be, Kunstverein in Hamburg (DE, 2021); Caos e Ritmo #1, CIAJG (Guimarães, PT, 2020); What is going to happen is not the future, but what we are going to do, ARCO Madrid (ES, 2017); 4th Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art - New Literacy (Ekaterinburg, RU, 2017); Destination Wien 2015, Kunsthalle Wien (AU, 2015); When elephants come marching in, (Amsterdam, NL, 2014); CCC: Collecting Collections and Concepts, (Guimarães, PT, 2012); 8th Gyumri Biennial – parallel histories (AW, 2008).

Images cortesy of Hugo Canoilas.

Sarah Lucas / Interior of The Grotto / Slideshow: Katharina Höglinger, Sílvia das Fadas / Georg Frauenschuh / Ana Vaz / Titania Seidl / Jannis Varelas / Performance Becoming Dog (Elise Lammer, Julie Monot e Lucien Monot).