Yonamine: PARLA_MUTE

In his latest exhibition in Berlin, Yonamine expands on his longstanding research into the language of billposting, unfolding it into an immersive installation that fills the walls and the floor of the gallery space. With a composite title that brings together Italian and English, Parla_mute opens up a space of contradiction between speech and muteness, highlighting a relationship between expression and repression, the individual and the collective. By creating this space of tension, the graphic materials accumulated by Yonamine over time are transformed and edited anew, in an amalgam of posters and silkscreens that cut across references and repeat key expressions. Amidst a plurality of images and typographies, one may read phrases and sentences such as "Sunlight," "Eurovision," "Antarctica’s thousands of species will have no voice," "The beautiful ones are not yet born," or "How To Get Glassy Skin in 7 Days At Home."

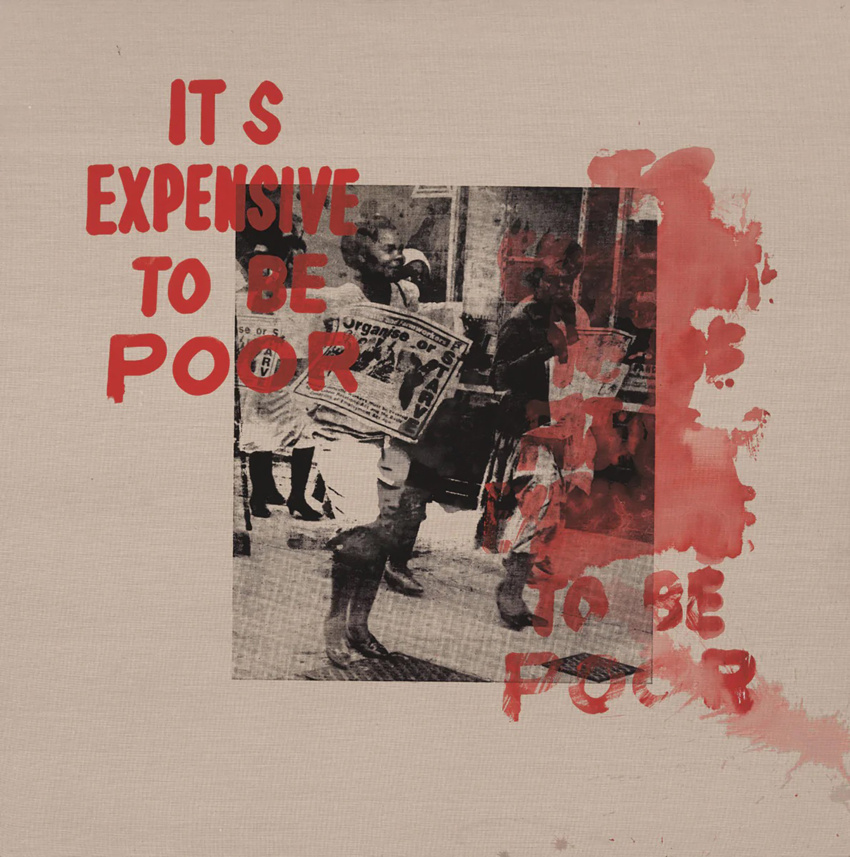

The street, which the artist calls an "ephemeral museum," is his main source of inspiration. For this exhibition, Yonamine resumes the art of collage by deploying synthetic, symbolic messages that rhizomatically weave the artist's universe, not only paying homage to the street but also giving some of what he has taken back to it—the artist stuck up hundreds of bills with the sentence "It's expensive to be poor" across the neighbourhoods he most frequented while living in Berlin. The aesthetic appropriated is one of necessity, of artisanal posters, of a constant struggle to remain visible amidst all this urban visual noise. Yonamine studies the poster as an instrument, as well as its typographies, expressions, and uses in public space. This analysis is carried out through what he calls "schizography," a methodology wherein he mixes different phrases and languages together in order to create new vocabularies and meanings.

Ana Salazar Herrera (AS): Could you begin by describing the installation Parla_mute within the gallery? How did you work out how to use the space? I very much enjoyed how the audience is completely immersed in the work, how you even used the window, and how several rolled-up bills in a corner make it look like the exhibition is still being set up, or like it might still change over time.

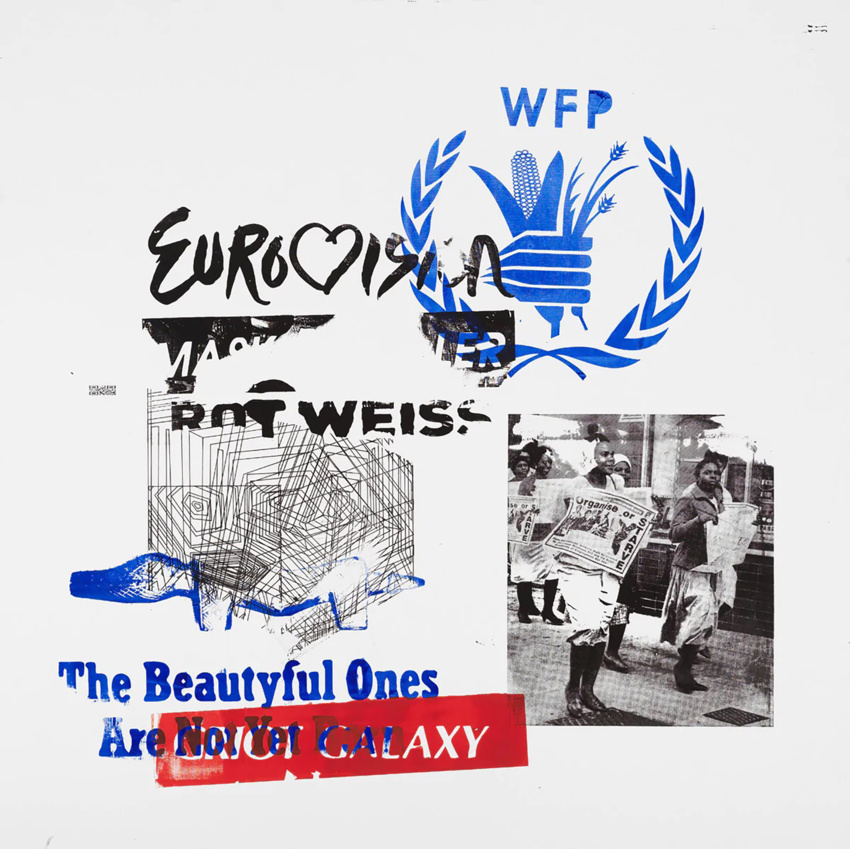

Yonamine (Y): First came the title. I knew I had an exhibition, but I still didn't have a title. One day, the gallerist called me: she was worried because they were already working on the exhibition's communication materials and needed a title. At that very moment, I thought of Parla_mute [just a term I came up with, something that sprang to my mind], as in a mute parliament, where people don't speak. Maybe because Angola's presidential elections were taking place at the time. People were talking, but no one was really understanding anything of what was being said. Politicians talk, but no one understands. For almost 50 years now, the same party has remained in power. I wanted to dedicate this exhibition to all Angolans who vote. I've never had the chance to vote because I've never been in Angola during elections. But then, guess what happens: even when there's the chance to vote, people tend to be rather ill-informed. Everything's done in a hurry, or just for showing off. I was moved because it is my country; so I started looking for political phrases, political logos. I used the World Food Programme logo again, this time on a photograph by the South African photographer John Liebenberg. I had already worked with images of his before. In the picture, a group of women hold a poster that reads "organise or starve." And I wanted to couple the "starve" and "organise" image with the logo of that institution. This was where the fun began. We are a wealthy country, but people still eat food from the trash. That was kind of my reply to this Angola, to this political sorrow of mine. And then I explored the space—not that big a venue, but you can also do sophisticated stuff in small spaces.

They prepared the floor to prevent the gallery from getting dirty. They didn't make preparations to exhibit stuff; rather, they made preparations for me to get the gallery as dirty as I wanted, and then to remove and pack it all up. I had two floors to myself, and because I rather enjoy playing with spaces, I planned to leave the upper one pristinely clean, with more of a commercial-gallery vibe, and to turn the ground floor into an exhibition-studio. It didn't really occur to me at the time that this was the underlying working process. I started cleaning my materials, making my first prints, and doing my tests on the floor before I moved on to the paper, which is usually how I work in the studio. The director of the gallery found it interesting; she said there had never been anything done like this in the gallery—works made from the floor—and sought my permission to use that floor, asking me not destroy it. I agreed, especially because this wasn't the first time I had left my work on the floor. I had already done similar things at Galeria 3+1 in Lisbon and at the São Paulo Biennial, for example. There is also a work I partly made on the floor at the Árpád Szenes-Vieira Silva Foundation. So, it wasn't exactly alien to the language I'd been developing for some time.

Meanwhile, at the time I was also bringing a collage exhibition to Berlin. My collages are quite inspired by the urban chaos of Luanda, in the street posters found across the city. They're not as big as the posters you see here, though. They're usually A4-sized, black-and-white photocopies, with job offers and ads, a bit like in the classifieds. In Luanda, over time and with the dust, they eventually get completely destroyed, and the aesthetics is beautiful.

Berlin and Europe provided me new working tools, new posters, new ways of presenting this collage. I hadn't done collage in a while and had been rather keen on doing other stuff, just trying things out. For Berlin, however, I felt the need to return to collage. Berlin is one of Europe's big urban centres; it has this street language, and boasts a very typical poster aesthetic. The way posters are stuck up on the streets, how long posters last in Berlin, their lifespan on the streets—all of it is quite interesting to me. In Berlin, depending on one's luck, a poster might last around two minutes on the street. You have to estimate how many posters you'd need to make for them to last and remain visible for at least 24 hours. For that, you'd need around a thousand posters, at the very least.

And so I challenged a friend, and we made two hundred posters with a sentence on them that had already been used for the exhibition at the José de Guimarães International Centre for the Arts, "It's expensive to be poor." I have been using that phrase ever since I was in Zimbabwe for a collaborative project with Pratchaya Phinthong, a Thai colleague and friend. We made the first series together with Pratchaya, and put the posters up in Zimbabwe. After that, we took it to the Pompidou Centre, but then the covid lockdown happened. Our exhibition stayed open for just one or two days. I felt a need to do something more than just filing this material away in the archives.

My work has a lot to do with music, as well as with the concept of sampling in music. I'm constantly sampling the same work, so I took the chance to make this connection to a frustrating situation. We had made an exhibition at such an important place, and it stayed open for just one day. My idea was to extend the lifespan of that sentence. Now it's in Berlin, out on the streets. The sentence came up during a conversation between friends in Zimbabwe. Someone said "It's expensive to be poor," Pratchaya wrote it on a piece of paper, and then we fancied working on it. The writer James Baldwin also wrote the same sentence. This notion is part of the concept of how he sees Blackness in the US. When I looked deeper into it, I realised it was part of Baldwin's discourse. But words can't be owned. Our planet is rich and belongs to no one.

AS: Let’s return to the phrase "It's expensive to be poor," which points to the incalculably high price that poorer populations have to pay. This sentence appears inside and outside the gallery, acting as a connecting thread throughout the space. On the one hand, it contains a rather straightforward message; on the other, it almost works like a somewhat veiled, subliminal message which, nonetheless, could be the key to deciphering the whole exhibition. Do you see it this way?

Y: Yes, that's essentially it. It is basically the heart of the exhibition, what breathes life into it. But the word "poor" does not necessarily refer to financial status. It doesn't need to be about economic poverty; it can have different meanings. I don't limit which type of poverty it alludes to. All I'm saying with it is that it's expensive to be poor. So there's room for all kinds of poverty: each one is expensive.

AS: Was "Parliament of the Mute" a poster you actually found? Or did you make it yourself?

Y: All of it was made. Even the "It's expensive to be poor" one. The sentence had been written down, but then I went to a market where people draw and sell street signs, and asked them to make me one. After they created this sentence on a poster, I used the same handwritten typography to recreate the aesthetic on paper. It came out a bit thinner, but the font is exactly the same.

Parla_mute was conceived from the idea of putting different phrases together. In my work, there's a series that I call "schizography," which is when I combine phrases in different languages in search of a new meaning. Instead of schizophrenic, it's "schizographic." It's an aesthetic I've been developing. Parla_mute is part of that—a mix of Italian and English. I want to create these phrases that do not exist in order to devise a new vocabulary, which will eventually become part of my work. The phrase "Parla_mute" may show up again in another piece of drawing or painting; it may return. It doesn't feature in this Berlin show. All of these phrases may return. They aren't unrepeatable paintings. Nothing is exactly the same, but I use the same icons. I create my icon and image archives, and then I use and abuse them. It's as if they were photographs, of which a gallery usually keeps several editions. To me, they are tools that allow me the time and space to think; I can repeat and produce the same picture over and over, and this way, whenever I need a certain phrase or idea, I never have to ask whoever's in possession of it.

AS: This mixture of graphic materials, of messages, of repeating and varying themes conveys a feeling of unease to me. How do you manage this feeling in the space? Or are you trying to find a balance between uncontrollable chance and a detailed, deliberate composition?

Y: I do different sorts of work, as though I were several artists inside a single one. I only need to picture myself on the street. There's a poster stuck up there that I really want to take home with me. Eventually I find a way to get the poster off the wall, but then it doesn't work as I expected, and I end up tearing a bit off. Then another poster appears; I'm the one who's vandalising them, but also someone who's being paid to stick posters up on the street. I've brought a poster of my own, and I stick it up onto the same surface. And then I think about how this new person wants to put it up. After it dries, or before it dries, I'm no longer a single person—now, I've got competition for doing collage too. I return as a competitor to the person who made the first collage. I stick up another poster over the existing poster. I create a competition between the various posters. If I stick up 100 posters on a canvas, it's as if I were 50 different people, and another 40 who want to remove their own poster. Eventually, a street aesthetic is created—an imbalance that I seek as balance. A certain question lingers: "was ist schön," what is beautiful, what is balance.

AS: I wanted to ask you about your most direct influences—or maybe about the key moments which have made their way into your work. You've spoken a little about the city of Luanda and your experience in Zimbabwe. Now you live in Greece, more specifically Athens, a city which has been undergoing major transformations as a result of touristification and gentrification, and where big social contrasts are quite apparent. On the other hand, Greece is a country that boasts a long history of activism, anticapitalist movements, and mutual support networks. Have you been following these kinds of demonstrations?

Y: Wherever I go, I try to let myself be influenced by whatever is going on around me. Unfortunately, when I arrived in Athens two years ago, the city was under lockdown, so I didn't see a thing. Or rather, whatever was happening was not where I lived, which was outside the centre, where the anarchists do their protesting. Even so, I met a group of people who make urban art. I kind of clung on to the street, and that was why, going back to the Berlin conversation, I decided to make posters on the street, not just inside the gallery.

In the end, the street is a source of inspiration. It’s an ephemeral museum. And of course, this museum needs to be supported. It's not enough to come onto the street, to feel the street, to take inspiration from the street, and not bring anything new to the table. In this case, my collage work is rather close to street aesthetics, so all I’m trying to do is give back to the street a bit of what I take from it. I want to be a part of this street language and not depend solely on the gallery.

Here in Greece, the street inspires me greatly—the street aesthetic, the way they write, the social issues they face. In the Guimarães piece, there's an almost empty room with a curtain which is inspired in Europa, the Greek goddess. These are the Greek influences which come up in my daily life here and which I'm starting to see in my work. I learned that Europa had been born in Phoenicia; she was a Phoenician princess who was seduced or raped by Zeus. I already knew a bit of Greek mythology, but now I'm more informed about it, having had a look at it from up close. I'm starting to understand a bit better who Sisyphus is, for instance. I enjoy mixing languages together to create "schizography"; and there are lots of cool, different fonts around here. There are lots of interesting visual stimuli, and I'll probably be adding this seasoning to my next works. Nothing palpable has come out of it yet, but I know it'll happen.

Junk collectors walk the streets wielding megaphones. I don't understand what they're saying, but I know they're looking for scrap metal. In the Guimarães exhibition, there's a sound piece which is a recording of a junk collector. So I'm already working with sounds from Greece. There's always an influence. I just let it happen. I've been here for two years, and I still haven't been to the Acropolis. I know the time will come for me to climb up to the Acropolis. I let things happen naturally. In my work, there's this aesthetic where it feels like an accident occurred which was not corrected. I let things move at their own pace; that's the law of nature.

The Berlin exhibition is quite experimental. It's this sort of work you dig doing in your studio. Of course, there are some moments of reflection—you have to choose the right phrases, use the right posters, tear the paper in the right spot—but it's fun. I get a rush out of doing collage at this scale. This exhibition has a lot of expression, a lot of movement, as it brings the interior and the exterior together. At a certain point, I wanted to rip chunks off of Berlin's walls—the posters in some places are like 20-centimetres thick. Seeing that also influenced my way of doing collage. I wanted to give back that part of Berlin that entered my work. It made sense for me to revisit collage, which had dominated my work for so long, and to show it in Berlin. I enjoyed it, and I also revisited myself as an artist through things I hadn't done in a very long time. I've also felt like doing it again but in the original way, the Angolan one, in black and white.

Galerie Michael Janssen Berlin

Ana Salazar Herrera [1990] is curator at the Ludwig Forum for International Art, Aachen, writer, and initiator of the Museum for the Displaced, a para-institution addressing issues of forced migration. Through undisciplined explorations of nomadic, poly-lingual, and transcultural subjectivities and expressions, her work proposes inventive ways of challenging established geopolitical world mappings. From 2016 to 2020, she was Assistant Curator for Exhibitions at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore. Ana was a curatorial fellow at Shanghai Curators Lab [2018], a mentee of the global exhibition program Project Anywhere [2020-21], and a curatorial fellow at Künstlerhaus Schloss Balmoral [2021-22]. She graduated with an MA in Curatorial Practice from the School of Visual Arts, New York, and a BA in Piano from the Music School of Lisbon.

Translation PT-ENG: Diogo Montenegro

Yonamine, PARLA_MUTE (2022). Exhibition Views, Galerie Michael Janssen Berlin, Photography: Gunter Lepkowski, Lepkowski Studios. Other images: Estefanía Landesmann. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Michael Janssen Berlin.