Max Ruf: Radio

"… here the water had become mirror-smooth; mother-of-pearl spread over the open shell of heaven, evening came on, and the pungence of wood fires was carried from the hearths whenever a sound of life … was blown over …."

Very seldom do we nowadays have the chance to see paintings on a non-white wall, indeed. That is, a wall of a purportedly neutral background, one unpolluted by particularities and sterile in its white and clear appearance. As we know, painting might request, or even demand, such a white surface because of the freedom and flexibility the latter provides to the arrangement and installation of the former, as well as to the clarity that proceeds from the play of light and reflections established in the space where the painting is presented and, ultimately, gazed at by viewers. However, it is intriguing to think about those other places, those other walls and surfaces where painting, in times past, used to take place.

At the beginning of what we usually call humanity, painting first appeared on cave rocks, in deep, damp, dark caves, and would later be admired in daylight on the carving of temples erected on top of mountains or on tombs underneath the deserts, on the friezes and chambers of old villas, on the ceilings of chapels and secret catacombs, on majestic cathedral domes, in huge, sumptuous salons, and in large or secluded rooms at home, in small studies, where paintings would be tenuously illuminated by unceasing light variations and vibrations emanating from a fireplace, by the drawn-out sparking of the burning wood. On more or less regular walls, in more or less ostentatious rooms, up until the age of the great Salons painting usually took place within utterly differentiated exhibition environments, which naturally differed greatly from the sterile white walls on which we have accustomed ourselves to locate the former. The viewer will surely not find it odd to come across works that seem mysteriously displaced, insufficiently autonomous, when exhibited on the neutral walls and within the sterile environment of a gallery or a museum. In fact, stories are told about certain paintings that are no longer observable under the exact lighting and from the correct angle as they have been removed from their original context, from the rooms where they were installed above a fireplace, a staircase, a cosy get-together of peers, or the seclusion of somebody meditating.

Certainly, those circumstances are long gone nowadays. Yet, it is a very peculiar occasion when we come across these unexpected situations, in which paintings not only are found by the viewer in the space, by virtue of its formality, but also surprisingly seem to find their form in the space where they are presented.

Max Ruf's exhibition Radio inaugurates the exhibition project Figura Avulsa, organised by artist Ana Cardoso and held in an old building by the Santa Catarina Viewpoint, in Lisbon. The first room was previously a kitchen—we recognise it by the large stone chimney and sinks, by the wall mosaics. The light is pleasant, and a single painting occupies the wall. Its title, untitled, is accompanied by a short parenthetical suggestion, or indication, of a description—"green, grey, red, blue." The same happens with the paintings presented in the adjoining outside space.

Then, the next moment of the exhibition takes place in the building's inner yard. This space is cold, damp; a manifestly autumnal sensation. But the oddness of observing paintings in an outside space is almost immediately mitigated by the clarity provided by the surrounding, indirect natural light flowing from the tops of the buildings. It is a limpid, homogenous, vitreous, almost aquatic light. The persistent sound of a ventilator is heard, contrasting with the sounds coming from a kitchen with a window to the inner yard.

One hears cutlery and plates being handled, tap water running, a short dialogue of voices, of honest laughter—the sounds of life, as Broch wrote. And, should one look around, the paintings seem to coinhabit that space, as though they had always belonged in it.

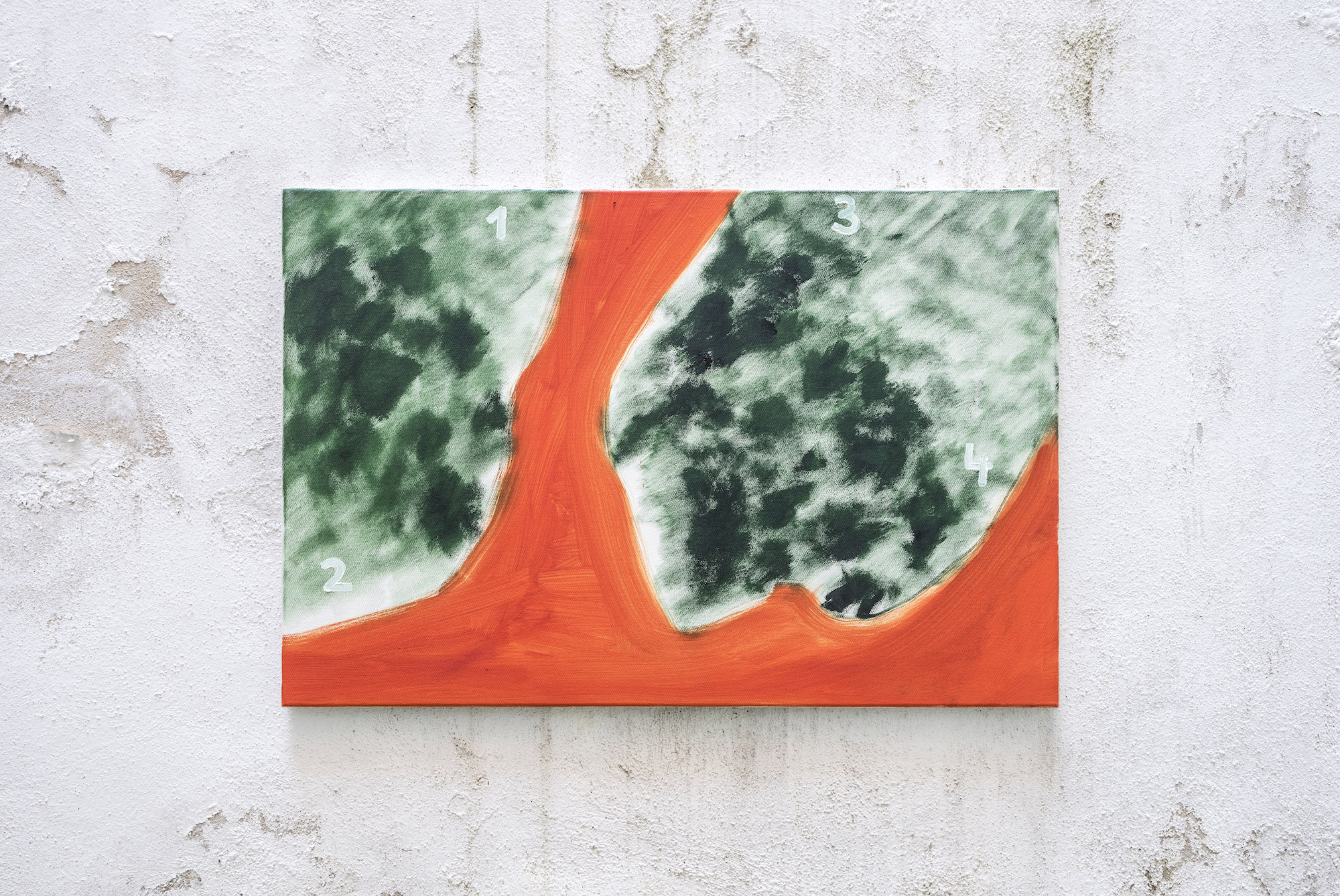

Suspended on that window fence, we find a painting of a light-green hue interspersed with three dark dots. In the abstraction of it, the application of diluted green paint on the canvas evokes reflections of light on ripples, indistinct reflections on water, onto which the contrasting dots emerge. In a play of veilings and unveilings, between transparency, opacity, and density, the dots seem to float, so to speak, over the indeterminacy of the background. In another untitled painting, a green grid rests on a translucent, aqueous blue, with another parenthetical direction: "blue, green line horizontal, two green lines, vertical." In front of it, another grid stands out from a field of indeterminate, irregular, strong-coloured shapes: "untitled (white lines, horizontal, green fields, horizontal, over yellow, orange and white wash)." Just like the latter coexists in a sensible, balanced way with the fence of the window onto which it has been installed and with the steps of the adjoining backstairs, a fourth painting emerges in this space. Its potential organicity becomes clear by virtue of being installed on a wall that, marked by time and dampness, encompasses and seems to coexist with the former. Finally, a wooden piece on the wall, titled objecto (dois). In a very particular way, this title seems to suggest a potential theme for the duality between elements and forces, of figure and background, of field and counterfield, weight and lightness, balance and imbalance that is clearly present in Max Ruf's paintings. Returning to the kitchen space and revisiting the exhibition's preludial painting renders the same conclusion.

As Rothko tells, just like the child instinctively begins portraying space by drawing a line on the bottom of a paper sheet to represent ground, and another at the top to represent sky, so the painter's gesture makes us recognise these forces, which substantiate our place in the world. The place we occupy between that which is farther or closer, between the horizon and that which takes on a vertical quality, between that which is above or below us, between that which is clarified ahead or concealed behind. That is where the impetus of painting is completed: upon the summoning of that environment where the sensation and experience of the movement of the body takes place, between retreat and approach, between prolongation and suspension—where, in Rothko's words, the fulfilment of an idea in painting "is determined by what representation of space it employs."[2]

In this case, the hiatus between what we see and the possibilities of what can be seen, what can be glimpsed, from the paths to abstraction, is fulfilled as the works effortlessly find their place in space. In this exhibition, the works know their place among old, damp, transfigured, greenish walls that have been eroded by the substance of time and weather. They emerge from a particular, limpid, familiar light, and become embedded among those brief, crystal-clear sounds of life. And, as Virginia Woolf rightly noted, "it is necessary to remember what one saw"[3] in order to preserve a certain moment. The "mark on the wall" evoked by Woolf, an unexpected image (is it "a nail, a rose-leaf, a crack in the wood?") above the chimneypiece, is brought to mind through the cigarette smoke, by the heat of the burning coals on a winter's day, by the film of yellow light on the book, by the flowers resting in the bowl, by the gentle sound of branches brushing against the window. Is that holistic memory, genuine experience of the sentiment of the real, not the "proof of some existence other than ours"—one engendered and perhaps fulfilled by abstraction in painting?

As it seems, gone are the times when one used to encounter painting upon those other walls, suspended above those other realities, observable in those other spaces where it would seemingly rise up and find its potential, intimate place. However, while we certainly cannot demand a permanent dwelling for painting, the latter, on occasion, certainly seems to make us instinctively and surprisingly recall and recognise that space we inhabit, where our body perceives itself as worldly and finite by means of these unexpected, life-endowed mise-en-scènes we, as viewers, gaze at.

Filipa Correia de Sousa (Lisboa, 1992) is an independent curator, essayist, and codirector of UPPERCUT, Lisbon. Master's in Philosophy-Aeshetics from FCSH: NOVA University, postgraduation in General Philosophy from FCSH: NOVA University, and bachelor in Painting from the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon.

Translation PT-EN: Diogo Montenegro.

Max Ruf, Radio. Exhibition views at Figura Avulsa. Photos: João Neves. Courtesy of the artist and Figura Avulsa. Works: Untitled (two green fields, one red field, 1-4), 2019, oil on canvas, 90 x 60 cm; Untitled (green, grey, red, blue), 2019-20, oil on canvas, 90 x 60 cm; Untitled (green, three green points, composition), 2020, oil on canvas; Untitled (blue, green line horizontal, two green lines, vertical), 2019, oil on canvas, 90 x 60 cm; Untitled (white lines, horizontal, green fields, horizontal, over yellow, orange and white wash), 2019, oil on canvas, 150 x 100 cm; Objecto (dois), 2020, wood, glue, screws.

Notes:

[1] Hermann Broch, The Death of Virgil, trans. Jean Starr Untermeyer, New York: Vintage Books, 1995, p. 13–14.

[2] Mark Rothko, The Artist's Reality. Philosophies of Art, New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2004, p. 55.

[3] Virginia Woolf, "The Mark on the Wall," in Monday or Tuesday, New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc., 1921 (italics added).