Pablo Echaurren: La Révolution R.S.V.P.

A Revolution impossible (today)

La Révolution R.S.V.P. is the first solo exhibition by the Italian artist Pablo Echaurren (Rome, 1951) in Portugal. Supported by the Italian Council, a programme aimed to promote Italian art abroad, the exhibition is an attempt to represent the complex, heterogeneous practice of an extremely atypical artist. Through a vast apparatus of works, some of which are shown for the first time, consisting of drawings, paintings, fabrics, newspapers, magazines, and various archival materials, Pablo Echaurren's exhibition is a story of the Italian cultural ferment of the 1970s that tried to propose, not only with force, a different culture.

The two floors of the Galeria Zé dos Bois have been invaded by a whole combination of signs which, like a river in full flood, overwhelms the viewer, plunging them into a chaos apparently devoid of any logic. A monographic exhibition of Pablo Echaurren is not a trivial matter; enclosing such an elusive practice within a rigid, sometimes pedantic mechanism would perhaps be counterproductive. In fact, the two curators seem to put aside any presumption of a unitary, total, exhaustive, and coherent representation of Echaurren's work, emphasising some aspects that characterise the Roman artist's practice and thought. First among them is a strong revolutionary potential, a sort of obsessive search for a way out of the mesh of a pre-established and predefined system, in order to generate a possible alternative. In another era we would talk about "avant-garde," but for Pablo and the historical, political, and social context we are referring to, we can easily use the term "revolution."

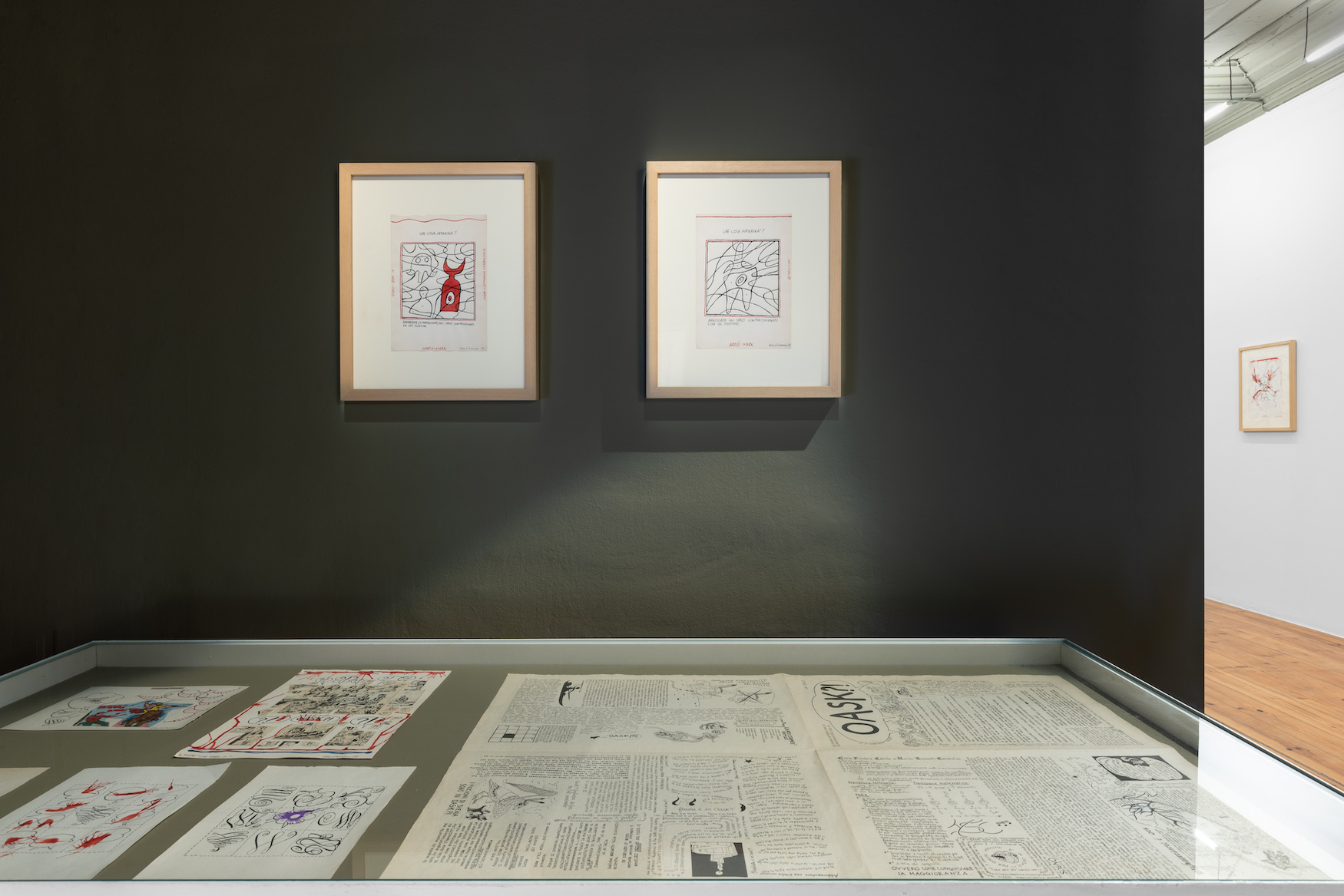

Already from the first rooms, a restless character begins to be outlined. Refusing the logic of the art system, in 1977 Pablo Echaurren decided to abandon his artistic career to join the Indiani Metropolitani’s movement, the creative and ironic wing of the Movement of 1977, which sought to unveil the mechanisms through which power generated consensus using politics and the media. Working mainly with illustration and comics, in those years he produced some fanzines, such as Oask?! and il Complotto di Zurigo, and signed comic strips for the most iconic newspapers of Italian left-wing political movements such as Lotta Continua.

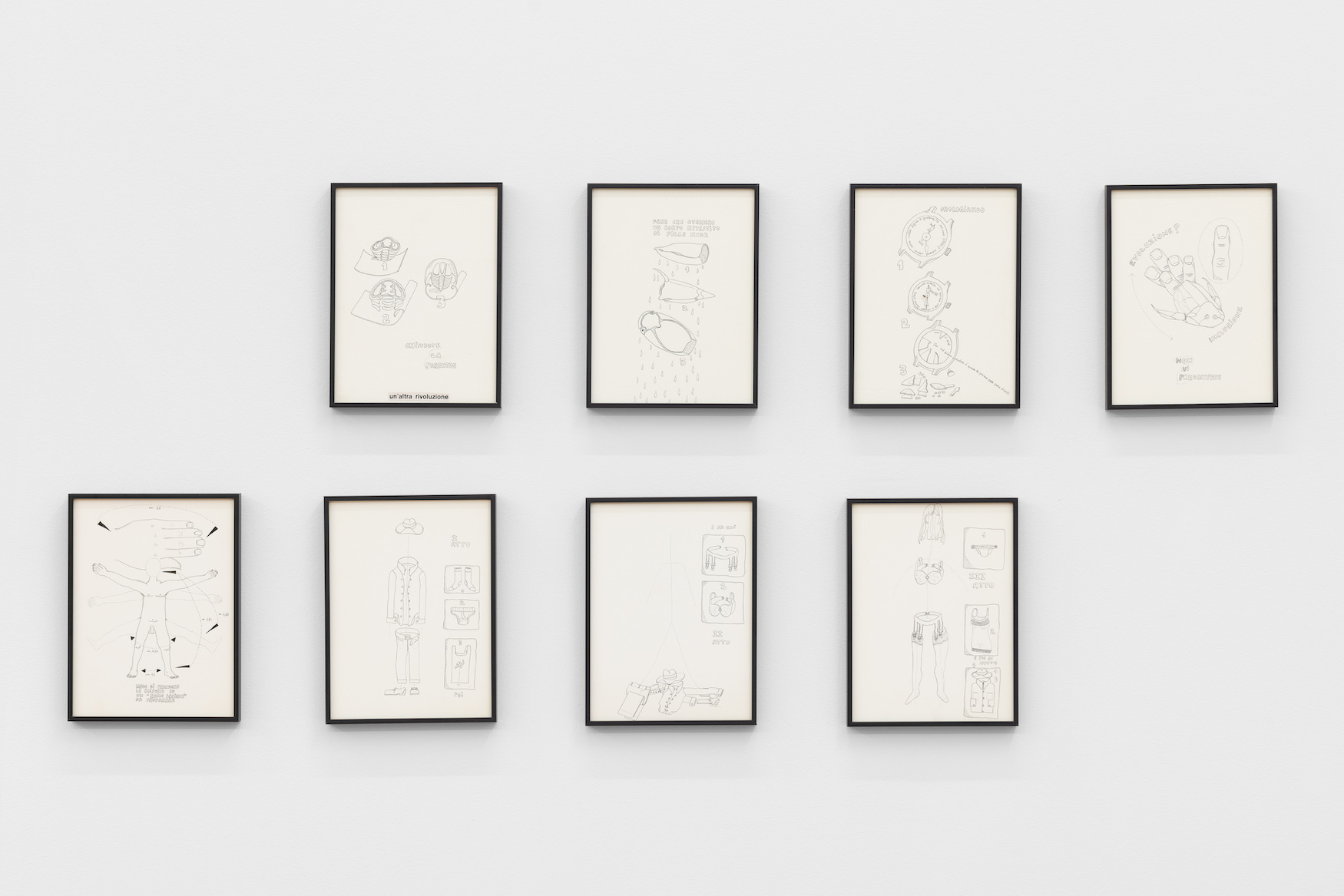

Even before joining the movement, Echaurren seemed to consider comics as an instrument of freedom. In spite of the "great figurative arts," comics were often seen as a "minor" art, an expression of low and superficial culture. But it was this minimal and light gesture that fascinated Pablo, who, among others, started to use comic drawing as a political form of dissidence. The many possibilities given by the medium have allowed an entire generation to experiment with an atypical, a-logical, non-rational, antagonistic idea of culture. Mimicking the classic structures of Western rationality (in the case of Pablo Echaurren, the grid and scientific classification systems), they tried to break through this rigid scheme, opening it up to new meanings. An attempt has been made, as a matter of fact, to lay the foundations of a proper counter-culture.

This is particularly clear in the comic strips' so-called “quadratini” (1970–1976), which we find in the third room on the first floor of the ZDB Gallery. Composed as real classifying studies, very minute and very precise illustrations, in reality, these works don’t seem to analyse or study anything. In a succession of variations on the same subject, they are explained only at the end with an ironic title that leaves us with a bitter smile on our faces. Looking at the lunar craters, the islands, the dinosaurs, the leaves as well as the flowers meticulously reproduced in these little squares, we recognise a reading order, the code immediately catches our eye, and everything is clear! But what seems to escape is the meaning. In a sort of Dadaist experiment, the language adopted by Echaurren in these, as in many of his works, seems to shun a predetermined meaning. Playing with the rationality of the structures through which we usually perceive reality, he makes our beliefs crumble and, with irony, invites us to cross the boundaries of common sense.

“Damned Metropolitan Indians, it’s impossible to understand a damn thing you're saying,” exclaims the cowboy trapped by the Native Americans in the homonymous work. And this is precisely the feeling that pervades the viewer in front of the “display cases” that classify small drawings and various ordinary objects, as well as in front of the representations of the “bachelor machine” of Duchamp and Picabia, which, probably malfunctioning, drip and spray red liquid.

However, by accepting Pablo's invitation, we can easily notice a sort of thread that connects all the works on display in the exhibition, up to the most recent ones on canvas. A stubborn lack of communicability is also evident in Echaurren's paintings, which in fact immediately appear strange to us—paintings composed by writings, not really paintings, definitely counter-painting. We still clearly recognise the code: writings, like graffiti on the walls, tell us about dissidence. But now, the antagonism seems to have been muted, and particularly in works such as Dolce stil provo, 2015, and Io, io & d'Io, 2017, we notice the individual letters banding together in a set of forms; although they could still say everything, they leave us with nothing to say. The artist still plays with an anarchic construction of meaning, personal, partial, and undefined. Once again, he leaves us alone, facing endless possibilities, with a dazed smile on our faces.

We proceed through the exhibition, staggering between comics that become patterns for soft fabrics and drawings that tell us how to measure a Homo sapiens, until we find ourselves in front of another painting, Caino e Babele / Lingue moribonde e lingue viventi, 2016. As when waking up from a long sleep, everything seems to come back, the classic speech bubbles are now empty, and coloured liquid drips like blood. Someone or something has been killed. Indeed, a murder was actually committed and probably the revolution died!

Looking back at all these fragments left here and there, putting them in a more contemporary perspective and abandoning a childish fascination with a bygone past, Pablo Echaurren seems to suggest that those tools that we still consider fundamental today for constructing an alternative are totally ineffective. The antagonistic background buzz, the constant oppositions, and the small revolutions applied in the name of a greater good—all of them are developed through anachronistic and nostalgic gestures. Absorbed by the same system they wanted to fight, these actions are confined in the museum’s rooms.

Abbiamo tanto amato la rivoluzione [We loved it so much, the Revolution], Alfredo Jaar wrote in neon. It honestly occurs to me that if we let it die like this, maybe that wasn't true love!

Enzo di Marino [Vincenzo Di Marino] is an Italian curator based in Naples. In 2018, he co-founded the curatorial project Bite The Saurus. He collaborated with the Prada Foundation, Milan; Madre Museum, Naples, among others. In 2019-2020 he was an assistant curator at MAAT.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro

Pablo Echaurren: La Révolution R.S.V.P. Exhibition views at ZDB: Galeria Zé dos Bois, Lisbon, 2023. Photos: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of the artist and ZDB: Galeria Zé dos Bois.