Marlene Monteiro Freitas: Idiota

Inside Pandora’s box, searching for unsounding mysteries

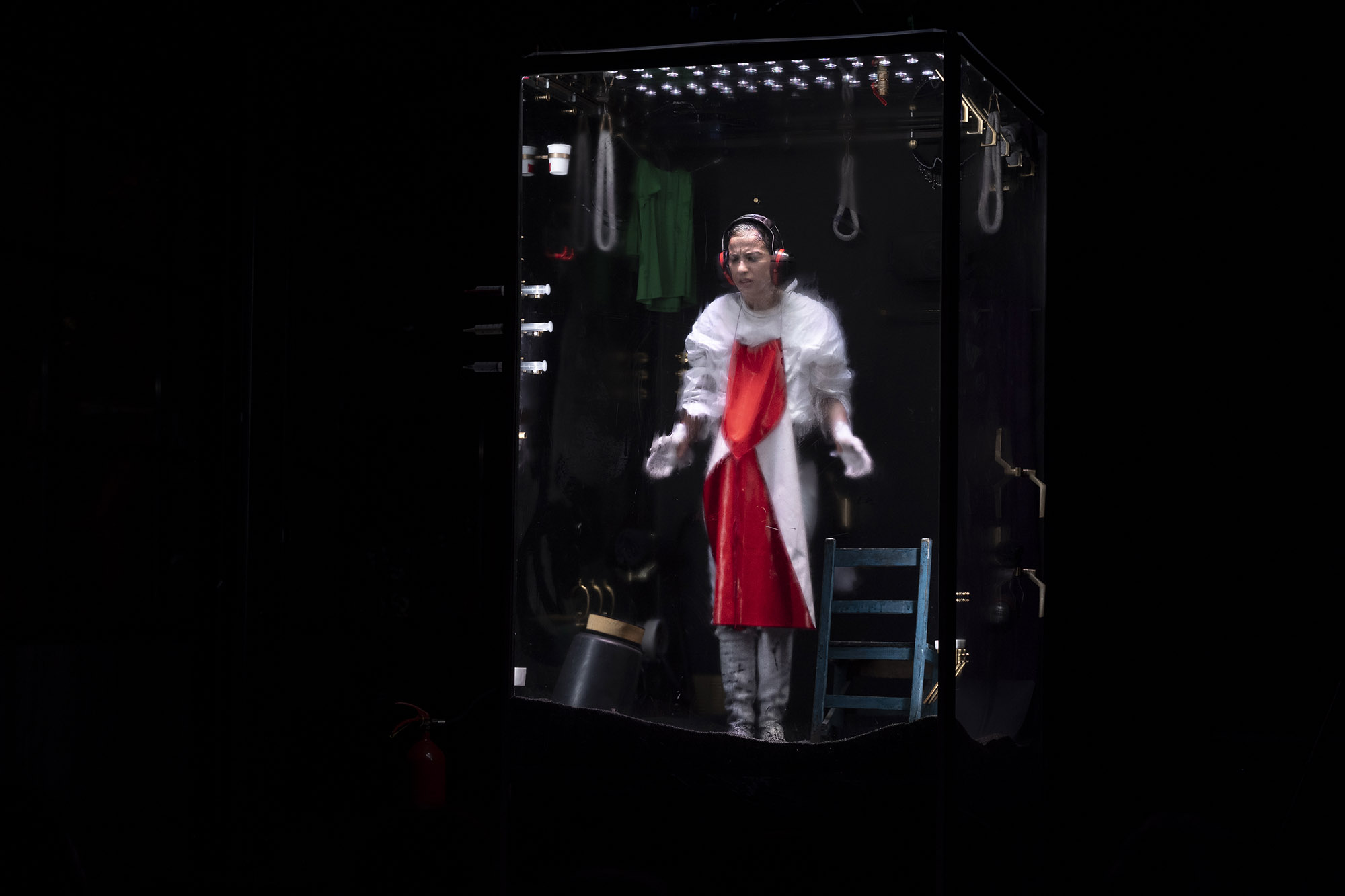

While entering a recovered old warehouse, now the K1 KANAL Center Georges Pompidou, the audience encounters a bewildering image: a transparent glass box where a strange headless figure with a human body, suspended by its arms on ropes, stands on a small blue wooden chair on a pile of dark sand. It is the first and striking image of idiota, one of the works that opened the Kunstenfestivaldesarts last May, and the most recent work by Cape Verdean choreographer and dancer Marlene Monteiro Freitas, who was awarded in 2018 the Silver Lion by the Venice Biennale, and in 2021 the Chanel Next Prize and the Evens Art Prize.

Although the stage builds up around this glass box, the work reaffirms a clear distinction between scene and audience. The glass box frames an almost pictorial canvas, creating images that progressively detach from its bidimensionality, gain volume and momentum, quickly expanding visuality to performativity, to the sound of a contrasting sonic landscape that grows throughout the performance, ranging from classic laments to vibrant Cape Verdean rhythms.

The suspended headless figure initially evokes a body on a cross, one of the archetype-images of death. As the audience settles in and the performance starts, the figure dressed in white pants, a green pullover and a roundish flat thing-head, begins by drawing precise and geometric arm movements, negotiating its weight on the ropes, while its legs tackle and measure the enclosed space. The performance continues by experimenting with and through the figure’s costume. While manipulating its green sweater, Marlene creates other images that resonate with the figural work we recognize from previous choreographies: the puppet, the mechanical doll, the sailor, the soldier, or even the faun or the satyr. In a permanent game of instability and metamorphosis, these figures do not crystallize but proliferate, in gestures that are articulated with the objects that populate the box: a bucket, a shovel, a funnel that opens to the inside, towels and other hanging props.

Expanding the choreographic to a performative installation, in idiota Marlene unravels not only theatrical protocols, but also shifts disciplinary boundaries between visual and performing arts. In addition, this work reaffirms some of her choreographic instruments such as hybridism, simultaneous contradiction and overdetermination, through a figural work that unfolds in porous figures negotiating the human, the cartoon, the hybrid, and the clownish.

Her prolific fictional imaginary sets in motion a fluid instability which knows no borders, binaries, and impossibilities. And like her other works, idiota is the result of a process of saturation and stubbornness, a determination of staying with the trouble until the work reaches the highest tension in its relation with the public.

Commissioned by CNAD, in Mindelo, Cape Verde, this work departs from an artistic dialogue between Marlene and her deceased friend Alex Silva (1979 - 2019), a Cape Verdean artist based in the same city where Marlene lived her childhood and youth. Born in Luanda to Cape Verdean parents, Alex Silva grew up in Cape Verde and graduated from the Willem de Kooning Academy of Arts and Architecture in Rotterdam. Silva had a prolific artistic activity between the Netherlands and Mindelo, where he founded in 2009 the ZeroPoint Gallery. In Rotterdam, he was selected to create a monument for 150th anniversary of the abolition of Dutch slavery in Suriname and the Dutch Caribbean, entitled “Clave,” inaugurated in 2013. Considered one of the most international Cape Verdean artists, his pictorial work operates from an intense process of overlapping visual references, rethinking identity politics between Africanity and the diaspora, and negotiating the intricate relationship between the human, the social and the political.

In idiota, we recognize not only notes of a chromatic palette that dialogues with Silva’s pictorial universe — red, purple, blue, white — but also contaminations in the unfolding of figures that coexist in the same space of the canvas and which, in Marlene’s work, also disseminate in the enclosed space of the glass box. Both in Alex Silva’s canvas and in Marlene’s choreographic realms we recognize a focus on the face expressiveness, on details such as a wide mouth that enunciates a scream, on hand gestures, and on the figures that gaze back the viewers.

Behind these aesthetic resonances, idiota confirms Marlene’s artistic methodology since it evokes an extensive theoretical excavation and a prolific montage of imagery, sound and literary references, processed and transformed into a final work of bewilderment and opacity where the viewer does not recognize the combined materials.

Echoing Silva’s own untimely death, Marlene draws on the myth of Pandora as an inspiration for this solo. Like many of the figures in Greek mythology, as well as the figures in Marlene's work, Pandora also embodies duplicitous natures and ambiguities. The exact origin of a myth is often difficult to pinpoint. In pre-Hesiodic mythology, Pandora, as the name alludes to [it derives from the Greek pān "all" and dōron "gift"] could be translated as "the-all gifted," and in an earlier version it was associated to earth and fertility. However, the canonized version of this myth was written by Hesiod, and it is in the Theogony [18th-17th century BC], and especially in The Works and Days [ca. 700 BC] that the name and myth of Pandora acquires another meaning, perpetuated until the Renaissance and present times.

In that version of the myth, after Prometheus had stolen the fire from the gods to handle it to the humans, Zeus decided to send humanity a punitive gift, to compensate for the benefit they received. Zeus ordered Hephaestus, god of Fire, to sculpt from earth and water the first woman who would be endowed with divine beauty and various gifts attributed by gods and goddesses: Athena taught Pandora the feminine tasks; Aphrodite the arts of the love and attraction; and Hermes bestowed on her a cunning mind and deceitful nature. Carrying with her an offering from Zeus, a sealed jar that contained all evils and misfortunes, Pandora would thus be the evil gift, and her descendants would bring ruin to humanity. Ignoring Prometheus' warning not to accept any offerings from the gods, her brother the titan Epimetheus, fascinated by Pandora’s beauty, marries her. Condensing in this female figure the ancestry of all women, it is still Pandora's inadvertent curiosity that motivates her to violate divine orders and open the jar, releasing all the evils that plague the mortal world. The only element that remained in the jar when Pandora closed it again was hope. Hence, according to Marlene, it is precisely this hope that her figure — probably not Pandora, but the figure of an idiot — seeks inside the glass box [a scenic object that clearly evokes Pandora's jar1].

Before devoting some attention to the figure of the idiot, it is noteworthy to argue how Hesiod’s version of the myth reflects the patriarchal society of Hellenistic Greece at the time, perpetuating the narrative that it had been a female figure, exemplified in Pandora, who would have introduced not only otherness and sexual desire that unleashed all pain and misfortune, but also it had been her curiosity and undue desire for knowledge that had caused the ruin of mortal society. This myth thus emerges as an epistemological warning to the threat that women's will to knowledge [Foucault 1990] would be considered inappropriate, undesirable, and deviant. Recognizing mythology potentiality to naturalize knowledge [Barthes 1972], this myth has had repercussions in Judeo-Christian theology, with a clear parallelism between Pandora and Eva2, two female figures who, according to the biblical narratives, by giving in to their will to knowledge were responsible for leading humanity towards a future of suffering and hard work.

However, in this dance work, the figure that enters Pandora's jar does not seem to be Pandora. A hybrid nongendered being, half human and half animal with its horse's tail, the figure seems to symbolize human struggle and desire of knowing the unknowable, that is, of looking for answers to the riddles of human destiny and its inalienable mortality.

Suspended by ropes, the figure tests the space that encloses it. Manipulating the green costume, it makes other temporary figures appear. Uncovering its human face, it negotiates its gaze between what it sees through the transparent box, and what is reflected on its condensed surfaces. With a shovel, the figure digs up the black gravel that covers the bottom of the box; it manipulates objects; it uncovers the lid of a funnel above itself, through which black sand flows echoing the sound and image of rain. The figure also carries buckets of black sand. It puts on the white shirt, takes off the white shirt, puts on the red latex apron, removes the apron, and hangs it elsewhere. On one moment it shoots ink jets to the outside, or the other it lets in a mass of green air inside, painting the atmosphere in green. While it once sketches expressions of regret and sorrow, it also moves its body in frantic and euphoric rhythms.

Negotiating dream and failure, good and evil, right and wrong, this idiot also echoes the idiot in Dostoyevsky's homonymous book, a character whose kindness, naivety and subversion of the social norms of behavior lead the mundane society that surrounded him to consider he lacked intelligence, while it was his convictions rooted in love and generosity that motivated his actions.

This idiota by Marlene may also evoke this figure, or fleetingly allude to the innocence of a Pinocchio, or to the arduous effort of Cape Verdean women who carry buckets of black sand on their heads to survive and feed their children, or even all those who persist in resilience in the search for hope, since it is only that, hope, what is left for the mortals in Pandora's jar.

From a pictorial fable that takes on a life of its own, to a magic box that invites us to explore our own limits and will of knowledge, with idiota Marlene invites us to navigate the tireless and inextricable search for the mysteries between life and death. And at the end, as one would expect, the idiot, like any other mortal, leaves the box knowing that no such answers can be found. Hence, refusing the will of representing the world, we are left with the certainty, in the wake of Haraway, that the world, as ourselves, is at the center of metamorphosis. Thus, like the idiota, we shall step out of the glass box and reconfigure our relationships in order to learn to stay with the trouble, hence, to live and die together in more than human unstable ecologies of permanent indeterminacy.

KFDA 2022 — Marlene Monteiro Freitas, Idiota. Photography: Bea Borgers. Cortesy of the Artist and KFDA.

Alexandra Balona is a researcher and independent curator. PhD Candidate at the European Graduate School & Lisbon Consortium, she is member of RAMPA, and co-founder with Sofia Lemos of PROSPECTIONS for Art, Education and Knowledge Production, a roving assembly for visual and performing arts. Member of Sinais de Cena editorial and scientific board, she writes dance critic at Jornal Público, and publishes regularly on performing arts.

Notes:

1 Although the most famous expression is Pandora's "box", it is thought that Erasmus of Rotterdam wrongly translated the Greek word "pithos", as it appears in Hesiod's version, to "pyxis", which would mean "box" or “small urn”. This lapse in translation distanced this myth and the figure of Pandora from its symbolic relation to Earth and fertility. “Pithos” were large jars that served for storing wine, oil or grain, and were partially buried in the ground. Pandora would also be a cult name of the earth goddess Gaia who, according to some historians, was the personification of the earth. This reference to Pandora’s jar is evident in Marlene’s idiota, since even though the glass box is not buried, it is partially filled with dark sand, resonating the image of being buried like the jars or “pithos”.

2 There is a clear resemblance between the figure of Pandora and the first female figure in Christian mythology, Eve, both having been created as the first women. According to Judeo-Christian exegesis, in the Garden of Eden, Eve eats the forbidden fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, inducing Adam to also commit this same primordial sin. Both Pandora and Eve are tempted by their desire for knowledge, and both lead from a mostly male Paradise to a humanity of hard work, physical and spiritual unhappiness.