Desejos Compulsivos: A Extração do Lítio e as Montanhas Rebeldes

Withstanding the compulsive capitalist dream of unlimited expansion, Compulsive Desires: On Lithium Extraction and Rebellious Mountains fosters intersectional alliances across disciplines in the face of climate emergency. Curated by Marina Otero Verzier for Galeria Municipal do Porto, the exhibition balances research, documentary and community works by drawing on global collective resistance to lithium mining and its contested use as palliative medication. The exhibition’s critical approach, based on Otero’s long-standing lithium research in Atacama, Chile, and beyond, combined with its timely opening, transforms international art views of the green energy transition into an active voice of collective resistance, supporting current protests over the six planned lithium mines in northern Portugal.

Its context in Porto as well as in the current lithium debate makes the exhibition incredibly important. Currently, the planned mining would create so-called "environmental sacrifice zones" to extract lithium, a key component of batteries in electric cars and other "green" solutions, to support Europe’s transition into green energy.[1] It also holds geopolitical implications, with Portugal’s lithium reserves estimated to be the largest on the continent—offering an EU-based solution replacing the current reliance on Chinese production of lithium for electric car batteries.[2] However, lithium extraction also consumes immense quantities of water and energy, pollutes waterways, produces toxic waste and destroys ecosystems and biodiversity in what is already an ecologically vulnerable territory.

The flagship of Portugal’s future lithium mining is planned by the British Savannah Lithium’s mega-sized open mine in Covas do Barroso. Driven by the urgency of the situation with Savannah submitting their Environmental Impact Report weeks prior to the opening of Compulsive Desires and the ongoing protests against the mine, the exhibition underlines its temporal and local context with the resistance song Brigada da Foice performed by activist group Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso playing throughout the exhibition’s first floor. The song comes from a three-part triangular video installation featuring Brigada da Foice (2023), directed by Paulo Carneiro, the commissioned animated film Montanha Invertida (2023) by Grupo de Investigação Territorial, which reveals the ecological and social destruction of lithium mining, and the documentary Não às Minas – Barroso, um Povo em Resistência (2021–2022) by collective Medios Libres con la Gira Zapatista.

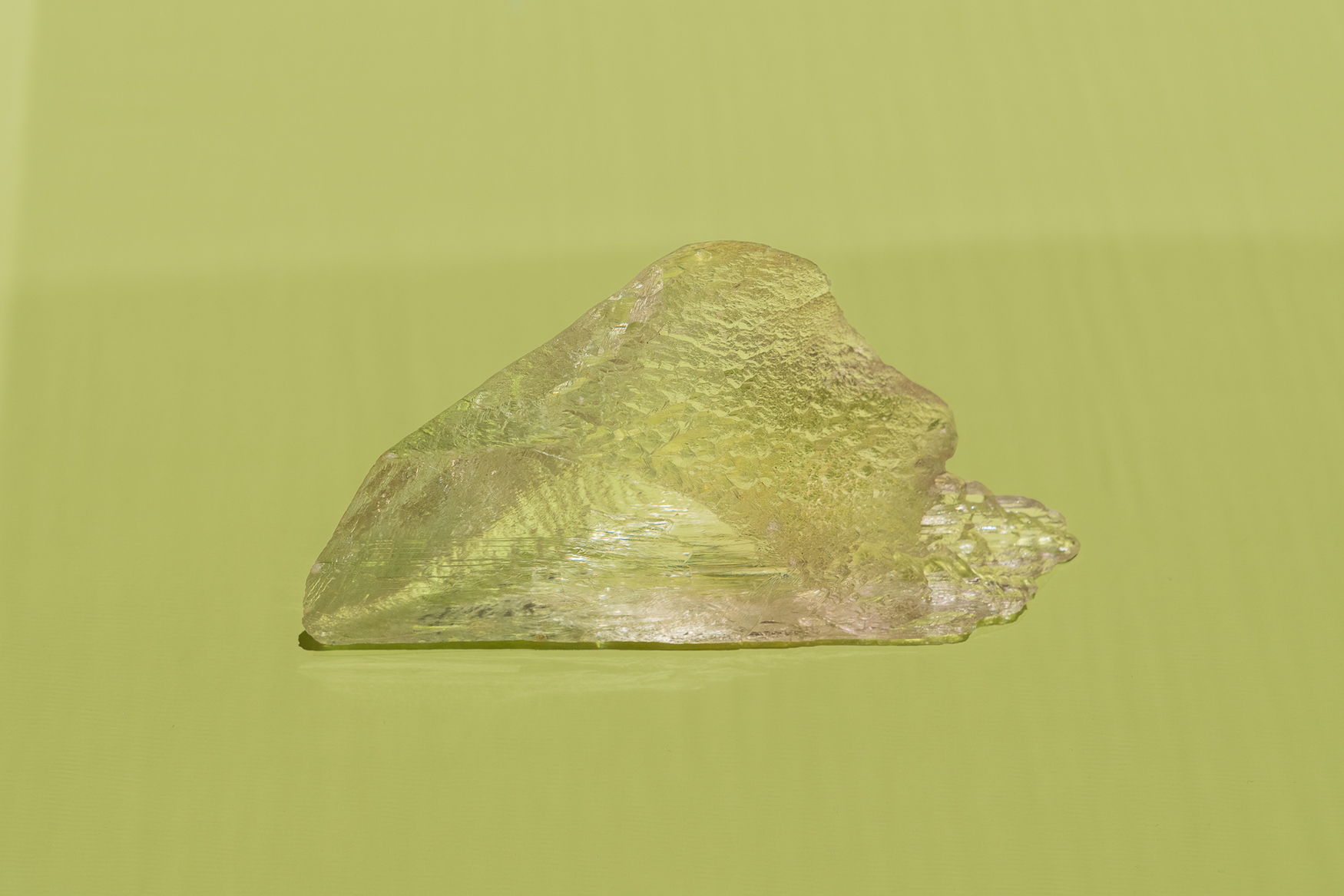

The triangle, three-way and thus the critical third way are recurring symbols of the show, encountered already at the exhibition entrance. Here, three ways of seeing lithium are introduced via three glass podiums at the entrance showcasing a small lithium-ion battery, a lithium-rich crystal spodumene from Minas Gerais in Brazil, and a small lithium carbonate PLENUR pill prescribed as a mood stabiliser, respectively. These represent the curatorial interpretation of society’s compulsive desires of lithium as the driver of the green transition; as an element to be extracted at our will; and as a tool for mood optimisation and population management.

Created within a booming eco-political contemporary art movement, Compulsive Desires positions itself within a radical futurist movement criticising an underlying, Western colonialist mindset that drives green capitalist "false" climate solutions through research-driven installations, video, performance and painted pieces by local and international artists, ecologists, psychologists, researchers and communities. The exhibition thus follows T. J. Demos’ approach "ecology-as-intersectionality"

Compulsive Desires differs nonetheless from related eco-political exhibition in its focus away from speculative futures. Instead, Otero brings our attention to community-based practices and stories of resistance that inspire hope. Examples are multimedia installations such as Medios Libres’ documentary Não às Minas, which draws on their previous lithium activism to speak on the destruction lithium mining will cause in Covas de Barroso, and Godofredo Pereira and Lithium Triangle Research Studio’s The Ends of the World (2020), which shows farmer, biologist and indigenous leader Rolando Humire speaking of his successful activism in resisting the ecological destruction of lithium mining in Atacama, Chile, among other inspirational and educational pieces. The exhibition’s basis is likewise one of community, with its prologue in May 2022 in the form of a seminar programme titled "Compulsive Desires: On Lithium Extraction, Endless Growth, and Self-Optimisation," which, just like the exhibition, brought international and local speakers to engage in collaborative, open-ended practices to counter the effects of extraction.

The seeds of successful climate crisis solutions are, the exhibition implies, already present in alternative, indigenous, traditional or local communities. Instead of inventing new approaches or satisfying itself with intellectual critique, Compulsive Desires sets out to build alliances and points of knowledge exchange between alternative, traditional, local communities across countries, political convictions, species and even mountains, which, as microbiologist Cristina Dorador implies in the featured multimedia piece The Ends of the World, will fight back against penetrative extraction.

The strong, fact-based beginnings of the show are followed by research- and community-based works by internationally famous artist names. Here we find photo documentation of Tomás Saraceno's and Aerocene Foundation’s Aerocene Pacha project in Salinas Grandes, which featured a hot air balloon powered solely by sun and air from the commons rather than relying on fossil fuels, batteries, solar panels or extracted elements. Orlando Vieira Francisco’s 2023 series The Observers’ Plateaus presents almost simplistic acrylic pieces in primary colours representing flattened mountains envisioned by the extractivist mindset as merely layers to be exploited—while Carlos Irijalba’s installation Pannotia (Lithium) (2023) includes a sculpture of broken pieces of used lithium mining drills that invoke an uncanny feeling of rape, penetration and wreckage.

Most impressive are Lara Almarcegui’s pieces Derechos Minerales: Volcán de Agras (2023) and Gravera (2021). The former documents Almarcegui’s successful obtainment of exclusive mineral rights on ore deposits through a certificate and technical drawings of the mountain’s subsoil. While drawing attention to questions of ownership, Derechos Minerales also implies the possibility to obtain extraction rights ahead of eco-colonialist mining conglomerates. Gravera is an earlier work showing the quarry excavation in La Plana del Corb in Spain being stopped by the artist for a day to welcome visitors—a practice Otero tells me Almarcegui continued, repeatedly halting works to slow down the excavation process and uncannily visualise the destruction. These interventions—ecoventions, to use Amy Lipton and Sue Spaid’s language[4]—are the contemporary evolution of environmental art acting to restore environments by actively hindering its destruction. In fact, the Compulsive Desires exhibition as a whole acts as an active intervention into the local environmental disaster that the lithium mines will bring with more supposed globalised implications due to the destruction of the ecosystem.

The nature of the featured works of the artists and collectives as happening in the real world of art and activism rather than in the gallery space creates a difficulty common to contemporary eco-political art: the impossibility of containing, explaining and emotionally impacting viewers through documentation of site-specific actions. This is in part overcome by Jonathan Uliel Saldanha’s mega-sized synthetic toxic lake, Psych Op Pump (2023), which transforms the museum space into an extracted inverted mountain, acting as a bridge of comprehension by visualising the lithium mining.

With this basis in documentation of the geological, ecological and social effect of lithium mining and its resistance, the exhibition continues on the second floor with a more philosophical and psychological approach. Upon entering, we are met with two rows of poles that face the viewer in a—once again triangular—militant formation. On the left they bear bright yellow posters, each with an illustration of a species extinct due to colonial crimes and signed with the word "comrade" in a different language for each poster. The piece, Comrades in Extinction (2021), is the artists Jonas Staal's and Radha D’Souza’s public demand for collective understanding and alliance-building across species.

The opposite row holds up traditional masks from the Trás-os-Montes and specifically Bragança regions carved by Amável Antão and Isidro Rodrigues, among others. The masks’ origin is in the midst of the contested mining region, where they are worn during festivities to invoke devils and animalistic figures, embracing the human and non-human alliance across worlds of being. In Otero’s words, "As their ecological and social degradation is presented as the lesser evil, communities in Covas invite devils into the public domain through the carnival. … If mining results in social breakdown, the political performativity of carnival alongside artistic expressions breaks social order to create counterworlds."[5] Their activist use is, however, not seen by the media in a positive light, which instead brands the ancestral and spiritual traditions of the communities instead as animalistic practices of communities that cannot comprehend the boom of jobs that the mining industry will bring.

The formation of comrades of extinct creatures and mountain devils is balanced with a meditation on obsession, The Grid (2018–2019), on the side wall. The series, created by psychologist Natalia de la Rubia during a period of mental health recovery, shows initially miniature watercolour squares becoming bigger and freer for each new piece. In the final part of the exhibition, we find Susana Caló’s Mad is Beautiful (2023), featuring a curtain stamped with pages of zines by mental health and bipolar groups fighting for the right to multiple mentalities instead of reductionist lithium-based medication, which primarily acts against manic episodes.

The show is completed by an archive of thermalism in Portugal, showcasing the longstanding history of the medicinal, lithium-rich water of local springs in the regions of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro. Scattered throughout the two floors of the show are video and painted works—the videos telling stories of successful resistances and the paintings showing simplistic yet impactful drawings of lithium- and mining-related symbolisms, proposing interconnection between humans and beasts, and a repeated theme of the Zapatistas as in Ranguy Pitavy’s commissioned piece Aujord’hui est un fauve, demain verra son bond (2023).

In these loving references to the region and haunting symbols and stories of mining, Compulsive Desires presents a critical question: how can we sacrifice one environmental zone for another? And is it not on grounds of economic, social and racial inequalities that some areas remain protected while others are sacrificed? To quote T. J. Demos: "How might cultural phase-shift infuse, energize, and direct new political organization, bringing militant and insurrectionary actions into relation with coalition-building and reclaiming an otherwise-corrupted electoral system?"[6] Compulsive Desires manages to tackle these questions of inequalities without crossing over from interdisciplinary, research-based art into politics by concerning itself instead with the very existence and alliance of humans and non-humans.

Herein lies the exhibition’s power and critical importance both for the localised debate on lithium mining and for a wider debate on what an ecologically viable solution to the climate emergency may look like. As Professor Marco Tedesco writes in a news article from the Columbia University’s Climate School, "Our dependence on lithium recalls that of oil and coal that transformed our society in the past."[7] And Compulsive Desires speaks to this very incompatibility of a green transition as the compulsive nature of extractivism of the earth being no different from colonial, world-dominating and psychiatric violence in other areas of our society: past, present and future.

Similarly, the recently published report from the UN Special Envoy for Human Rights and the Environment reads that "zones of sacrifice are completely incompatible with the human right to health and ecologically balanced environment" as enshrined in the Portuguese Constitution.[8] The paradox of sacrifice zones and environmental destruction becomes all the clearer with Compulsive Desires’ repeated imagery of penetration that sets the emotional backdrop of the exhibition through the mountain drills of Irijalba’s Pannotia (Lithium), as well as documented and illustrated imagery of open mines that literally replaces mountain tops with acid lakes alike Saldanha’s Psych Op Pump installation. If this is the result of green mining and a necessary sacrifice, then there must be a better technological solution—or even better yet, a shift in global understanding. Perhaps we ought instead to follow in Otero’s footsteps and build bridges, alliances and networks of community action, as solutions to the climate emergency might already be there.

Maria Kruglyak is a researcher, critic and writer specializing in contemporary art and culture. She is editor-in-chief and founder of Culturala, a networked art and cultural theory magazine that experiments with a direct and accessible language for contemporary art. She holds an MA in Art History from SOAS, University of London, where she focused on contemporary art from East and South East Asia. She completed a curatorial and editorial internship at MAAT in 2022 and currently works as a freelance art writer.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro

Desejos Compulsivos: A Extração do Lítio e as Montanhas Rebeldes. Exhibition views at Galeria Municipal do Porto. Photos: Dinis Santos. Courtesy Galeria Municipal do Porto.

Notes:

[1] Aline Flor, "Da Avenida da Liberdade às minas de lítio em Boticas, os alertas da ONU a Portugal," Público (26 March 2023): publico.pt/2023/03/26/azul/noticia/avenida-liberdade-minas-litio-boticas-alertas-onu-portugal-2042852.

[2] Jack Lifton, "China Controls the Lithium Market and All the West Can Do (For Now) is Watch," investor intel: the stock source (27 March 2023): investorintel.com/critical-minerals-rare-earths/china-controls-the-lithium-market-and-all-the-west-can-do-for-now-is-watch/.

[3] T. J. Demos, "Introduction," Beyond the World’s End: Arts of Living at the Crossing (Duke University Press, 2020), p. 11.

[4] Sue Spaid, Ecovention: Current Art to Transform Ecologies (Contemporary Arts Center, 2002).

[5] Marina Otero Verzier, "Compulsive Desires: On lithium mining and rebellious mountains," exhibition brochure (Galeria Municipal do Porto, 2023).

[6] T. J. Demos, "The Great Transition," World’s End, p. 171.

[7] Marco Tedesco, "The Paradox of Lithium," State of the Planet: News from the Columbia Climate School (18 January 2023): news.climate.columbia.edu/2023/01/18/the-paradox-of-lithium/.

[8] Aline Flor, "Da Avenida da Liberdade às minas de lítio em Boticas, os alertas da ONU a Portugal," Público (26 March 2023), my translation: publico.pt/2023/03/26/azul/noticia/avenida-liberdade-minas-litio-boticas-alertas-onu-portugal-2042852.