O Quilombismo

O Quilombismo: Of Resisting and Insisting. Of Flight as Fight. Of Other Democratic Egalitarian Political Philosophies

Resignifying an entire institution to make room for O Quilombismo in Berlin

The House of World Cultures (HKW) in Berlin, built in 1957 as a congress hall gifted by the United States and repurposed into an arts venue in 1987, was closed for several months of renovations, having recently reopened with a big bang under the new Artistic Directorship of Cameroonian curator Prof Dr Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. A new collective universe has thus begun to expand within and outside the walls of this prestigious and unique institution. Every single brick seems to have been resignified in order not only to rethink and problematise, but also build and practice the concepts of House, the ideas of World, and the complexities of Cultures. Before delving into the profoundly moving inaugural exhibition, for which the entire curatorial team has worked on collectively for over a year, let us first study the strong acts that will remain beyond the end of the exhibition. Together, they articulate the incoming team’s deliberations and proposals about the role an art institution of our times must play.

Starting from the outdoors, any flagpoles originally intended to glorify nation-states have been permanently reinvented as exhibition spaces. The garden at the main entrance will continue hosting a series of commissions dedicated to socially engaged architecture from different parts of the world to build welcoming gathering spaces. The disturbing Benjamin Franklin quote, engraved into a wall in the entrance hall, was sent out to friends, colleagues, and philosophers, who were invited to respond and think with and against Franklin. The quote reads “God grant that not only the love of liberty but a thorough knowledge of the rights of man may pervade all the nations of the earth, so that a philosopher may set his foot anywhere on its surface and say ‘This is my country.’” Such a claim may be read as a basis to validate and perpetuate the violence of colonialism and its legacies.

The new statements were embossed into translucent colour structures that are now hanging in front of the original quote, which although not erased, is now challenged, covered, replaced. One such plaque by French thinker Françoise Vergès reads “In a state of permanent war and systemic violence, this is a space to practice revolutionary peace and work towards reparation and communizing. Let’s create a world where the right to breathe and to love is truly planetary.” Another one by Jamaican sociologist Erna Brodber states “The breaking of yams amongst the Akan in Ghana at the beginning of the year is the symbolic act of sharing the basics of life. We pray that the flying pieces take with them their goodness to all people.” These also convey postures of respect and dignity that set the tone for the cleansed foundations of the House.

Perhaps the most significant proclamation of all is the renaming of various different spaces in and around HKW. Halls, rooms, foyers, gardens, the auditorium, the library, terraces, entrances, offices, the reflecting pools, stairs, a bar, and other spaces have received the names of 38 significant women from around the world. Women’s stories, historically erased, inhabit every square metre we cross, every particle of air we breathe. Remembering and honouring these great women is a movement towards repairing the unsurmountable loss and oppression that the patriarchy forces upon us daily. The spaces become archives of herstories and the visitors will either already know these figures or become familiar with them through the noticeable signage that elucidates who they are or were.

The Semra Ertan Garden is a homage to the Turkish activist and poet who set herself on fire at the age of 25 to protest rising intolerance and hostility towards immigrants in Germany. The main entrance bears the name of Hedwig Dohm, a feminist thinker and playwright from 19th century Germany. Marielle Franco Space remembers the Black Brazilian politician who was murdered in 2018 for defending the human rights of racially and sexually discriminated individuals against police brutality. Ethiopian pianist and composer Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou christens a space, too, while Martinican journalist and leading voice of the Négritude movement Paulette Nardal gives name to the upstairs terrace. The Auditorium is called after the one and only Miriam Makeba, South African singer, composer, actress, and anti-apartheid spokesperson, while the Library belongs to the great Lebanese-Palestinian writer May Ziadeh, pioneer of feminist Arab literature. The main foyer on the ground floor is dedicated to the seminal work of Jamaican writer and theorist Sylvia Wynter. Nearby a Hall is dedicated to Brazilian Black radical thinker and poet Beatriz Nascimento, who “dedicated much of her work to the quilombos, autonomous communities of resistance established by enslaved people and their descendants, as part of her academic research but also as part of her personal trajectory in the anti-racist struggle.”

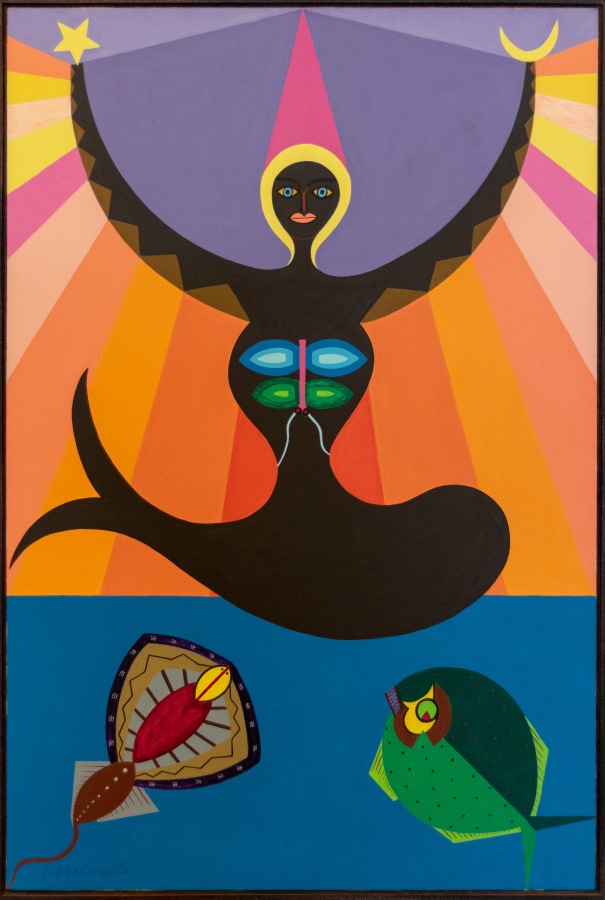

This takes us to the concept of the current exhibition, precisely titled O Quilombismo: Of Resisting and Insisting. Of Flight as Fight. Of Other Democratic Egalitarian Political Philosophies, occupying every possible and impossible space of the House with the contribution of 68 artists. With the renaming of the spaces, there is also a layered dialogue taking place between them and the works they host. The artistic and theoretical work of Abdias Nascimento is in many ways key not only to understand the curatorial intent, but also to decipher the colour code that permeates the walls, floors, display structures, and seating arrangements. The scenography, in the hands of Studio Bel Xavier, takes its vivid hues of violet, pink, orange, blue, green, and yellow from Nascimento’s stunning 1972 painting Oxunmaré Ascende (Oshumare Rising), depicting the androgynous spirit of the rainbow that represents the connection between the earth and the sky and symbolises persistence, movement, and wealth.

Abdias Nascimento defines quilombo as meaning “fraternal or free reunion, or encounter; solidarity, living together, existential communion. Quilombist society represents an advanced stage in sociopolitical and human progress in terms of economic egalitarianism.” It is with this premise that O Quilombismo brings together a wide range of artistic and research practices, many of which stem from or reference Afrodiasporic spiritual practices such as Brazilian Candomblé, Haitian Vodou, Cuban Santería, and others. Nascimento states: “Experience and science; revelation and prophecy; communion of humans and deities; dialogue among the living, the dead, and those unborn, Candomblé marks the point where African existential continuity has been recovered. Where human beings can look at themselves without seeing a reflection of the white face of the physical and spiritual rapist of their race.” He explains that the Orishas are the basis of his artwork, since their cult within Candomblé are the foundation of a deeply knowledgeable process of freedom fighting.

Located in the Beatriz Nascimento Hall with violet walls, fuchsia floor, and a brown freestanding, curved wall, Oxunmaré Ascende and other paintings by Abdias Nascimento hang next to three square photographs from the late 80s by Nigerian-British artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode, the son of a Yoruba priest, who queered the vocabulary of Yoruba deities through portraits of nude Black men wearing or holding masks, feathers, plants, fruits, and other objects. Four recent paintings by members of Taller Portobelo, founded in 1995 by artists from the Portobelo Congo community in Panama, honour the artists’ lineage tracing to cimarrones, self-liberated Africans. They depict the sovereign ruler queen María Merced, a herbal healer, a macaw king, and the immense strength of cimarrones (Judimingue nunko modidá [Cimarrones never die], 2019) in a unique Afro Congo style using acrylic paint, pieces of broken mirrors, feathers, and shells. An intricate long #Map from 2021 by French artist Marie-Claire Messouma Manlanbien reads “Ce corps est le nôtre ainsi croisé” (This body is ours thus crossed), layering jute fibre, raffia fibre, hair, metallic threads, resin, and other materials to trace histories of African people, weaving various socio-political threads together. Patchwork Culturel (1979), a painting on leather by Moroccan modernist artist Farid Belkahia, which draws on traditional Berber culture and Tuareg symbolism to compose a pictorial language of geometrical shapes and Tifinagh letters, is put in dialogue with Ghanaian artist Owusu-Ankomah’s Microcron Begins No.19 (2013), a black-an-white painting depicting adinkra symbols of the Asante people in Ghana. Both are examples of ancestral dictionaries that express a collective wisdom and knowledge of a people.

In the Mrinalini Mukherjee Hall, a large floor mural by Nontsikelelo Mutiti titled Kubatana (togetherness / unity / connecting / touching / holding) serpentines triumphantly along the entire orange floor. The black pattern of braided African hair celebrates this ancestral medium not only as an expression of African culture and knowledge, but also as a political language that has been used as a mapping system to escape bondage. It connects the various freestanding pieces in the open, sunlit room, such as Shipibo-Conibo artist Celia Vasquez Yui’s The Council of the Mother Spirits of the Animals (2020/2023), an amphitheatre with painted ceramic sculptures of 16 different animals, including a human, or Candomblé priest Moisés Patrício’s Aceita? [Do you accept?] (2013–ongoing), a series of 12 photos installed in a circle, each photo depicting the artist’s open palm generously offering something, thus proposing a non-transactional gesture—a gift.

Against the deep blue walls, the arresting glass beads canvases by Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunters Demond Melancon stand out, stemming from the Black Masking Culture of New Orleans, a subculture that started in the 19th century when Native Americans helped enslaved African runaways. Melancon’s rich and intricate depictions of this history are part of the flamboyant suits he creates yearly to wear for Mardi Gras Day, St. Joseph’s Night, and Downtown Super Sunday, inspired by legendary African kings and leaders, such as Shaka Zulu Fasimba and Haile Selassie, self-liberated Africans in the Americas, such as Bras-Coupé, who led rebellions against slavery, and Native American leaders who resisted colonization. There are also several hand-stitched and embroidered Siddi kavands, vibrant Afro-Indian quilts made with repurposed textiles by members of Siddi communities from the western coast of India, descendants from the Bantu people of eastern African. These abstract textiles are guardians of the knowledge and histories of the people who make them. Together with numerous other textile pieces in the exhibition, they open questions of narration and of how to tell the larger story of the communities they stem from.

In the Sylvia Wynter Foyer, the architecture has been fully embraced when commissioning site-specific pieces such as Amina Agueznay’s intervention with naturally dyed thread around six columns, creating a warm welcome that interrupts the modernist symmetry of the building, with the henna ensuring an auspicious start for HKW. Tanka Fonta, Cameroonian composer, artist, author, performer, poet, and researcher, painted a 9-part musical score mural titled The Cosmogenic Interconnectedness ‘How Did We Talk Before the Roman Alphabet?’ The Picto-Sonic Dialogues I, a symbolic composition of non-verbal language outside of thought and within deep time that circles around the foyer in a narrow path and was live interpreted during the opening.

Art surrounds the House from the outdoor, too. Nigerian-American artist and writer Olu Oguibe was commissioned three 7m-wide flags over the terrace, visible from afar and the Government District. Three identical flags with the colours black, red, gold, and green combine the Pan-African flag, the Australian First Nations flag, and the German flag, bearing the initials DDR, which stand for Decarbonize, Decolonize, and Reparate / Repatriate / Rehabilitate, touching the nerve of our times while simultaneously reflecting the cold war history of the site. The façade walls of the building, left and right of the main entrance, are covered by two powerful series of seven panels each by Brazilian visual and Carnival artist Alberto Pitta, a pioneer of Afro-Bahian print inspired by the orishas. His canvases gently protect the house with a visual storytelling that, on one side, delves into the world of Ogun, the Candomblé orisha known as the path opener and cultivator, and on the other side studies and celebrates the aesthetics and systems of communal housing in Brazilian quilombos.

As Ndikung writes in the exhibition’s handbook, “quilombismo manifests itself as a philosophy of resistance through joy, as a space of practice of the technologies of enchantment, as real and facultative spaces of bliss and elation conceived around ethical and egalitarian values.” HKW has made its mission to become such a space, where the body and mind can free themselves—a space to retreat, repair, recalibrate. The feeling of being immersed in the philosophy and history of Quilombismo is healing and strengthening. All curatorial choices reflect a conscious need for multiplicity and astructurality, with the understanding of Quilombismo as an ongoing process that requires cultivating.

There is therefore no room for alleged neutrality, nor white cubes and grey backgrounds. Instead, we find a multi-sensorial feast that welcomes languages of all kinds, spoken, unspoken, musical, symbolic, spiritual, bodily, human, non-human. The languages that have been carried within and have survived through people’s minds and bodies, despite the unspeakable violence against those same minds and bodies. Quilombos started during the instituting of colonialism and capitalism, the legacies of which continue to run deep in our hyper-capitalistic societies. As a cultural institution in the heart of Europe, HKW is not only finally acknowledging and honouring Berlin’s profoundly multicultural identity, but is also crafting itself as a space where the process of resisting cultural colonization and imperialism today can be nurtured. May all the powers, embodied knowledges, sonorities, sororities, talismans, amulets, berimbaus, stars, good wishes, and the love visibly poured into this inaugural project by everyone involved safeguard this spirited commitment.

HKW [Haus der Kulturen der Welt]

Ana Salazar Herrera (1990) is a curator and writer, founder of the Museum for the Displaced (2019-ongoing), and currently Assistant Curator at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, Saudi Arabia. She explores nomadic, poly-linguistic, and transcultural subjectivities, proposing inventive questionings of hegemonic geopolitical mappings. She was interim Curator at the Ludwig Forum Aachen (2022-23), Germany, and Assistant Curator of Exhibitions at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (2016-20). Ana was Curator-in-Residence (2021-22) at Künstlerhaus Schloss Balmoral, Germany, mentee of the Project Anywhere programme (2020-21), and a fellow at the Shanghai Curators Lab (2018). She has an MA in Curatorial Practice from the School of Visual Arts, New York, and a BA in Piano from the Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa, Portugal. Her writing has appeared in art magazines, exhibition catalogues, and the academic journals Afterall and Stedelijk Studies.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro.

O Quilombismo: Of Resisting and Insisting. Of Flight as Fight. Of Other Democratic Egalitarian Political Philosophies, 2023. Exhibition views at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW). Photos: Laura Fiorio/HKW. Courtesy of HKW.