Emancipação do Vivente

Emancipation of the Living presents an intersectional, critical discourse of empowerment and active resistance to injustice, violation and displacement of the human and the non-human. It is the first exhibition curated by Museum for the Displaced (Mf D), who have spent the past three years developing an alternative curatorial methodology by holding artist programs and residencies that give space for care and slowness, unlearning result-focused institutional frameworks and production demands, and choosing instead to support and use art to build inclusive futures.[1]

Shown across the Municipal Galleries of Lisbon (Galerias Municipais de Lisboa—Galeria da Boavista) and of Almada (Galeria Municipal de Arte), Emancipação do Vivente carefully balances the two spaces with the widely varied investigations of the seven invited artists and collectives.[2] The three members of Mf D—Ana Sophie Salazar, Mohammad Golabi and Leong Min Yu Samantha—approach the duality of the space with numerical equality: three commissioned and one existing work per space; one collective "acting as a bridge"[3] across the two spaces; while the remaining six participants are divided equally between the locations.

This grounds Emancipação do Vivente as a site- and time-specific project with two roots: the Lisbon space, with its international implications, sets the stage for responses to Europe as a colonising territory of races, histories and sexualities, while the Almada gallery shows localised movements of multiple resistances to issues related to land, encompassing eviction, erosion and extraction. Thereon, artistic investigations of "emancipation" of the displaced are played out: self-emancipation, collective emancipation, the emancipation of the urban landscape, of the soil, of the mountain; an intersectional statement first and foremost, as ‘Mf D understands Dis place/ment in an expansive way—something that can happen to humans and to non-humans … a physical, mental, and/or emotional way."[4]

Most pressing, and perhaps thereby most impactful, are two works that consider current, local emancipatory struggles: Frame Colectivo’s pro-sedimento (2023) and ETC’s Alto Tâmega no Chthuluceno (2023), both showcased in Almada. The former occupies the ground floor of the gallery, presenting the ongoing displacement and resistance hereto of residents of 2.º Torrão, Trafaria. The neighbourhood, where Frame Colectivo began a community-driven construction project in 2017, is located less than ten kilometres away from the gallery—the locus of a looming threat of coastal erosion that has come to a head with council-ordered demolition of homes due to the increased risk of flooding caused by construction on top of an underground waterway. Video and photography pieces raise awareness of the existential threat, worsened by the council’s failed planning that threatens to dispossess over 60 families of their self-built homes—often without realistic and just housing solutions.[5] The pro-sedimento installation is framed by an image of a bulldozer covering the window, photographs of the rubble of buildings mounted on the ceiling and a sound installation of house demolition. The latter is echoed by building works in front of the gallery, together creating a palpable feeling of impending doom countered only by the calls for direct action indicated in an informative timeline of resistance activities.

The second is architect studio ETC’s commissioned piece Alto Tâmega no Chthuluceno. Located on the floor below, it shows the expected dispossession and displacement of the environment caused by planned lithium mining in northern Portugal. Here, too, documentation of ongoing action is central with the mining companies’ to-be-approved environmental impact reports neatly positioned in protruding plastic cases on the wall. On one side of the reports there are large-scale photographs, and on the other a detailed mapping, both seemingly of the territories in northern Portugal. The totality creates a speculative story of the problematics in Montalegre and Covas do Barroso as simultaneous locations of lithium mining projects, power stations, agricultural projects and endangered species.[6]

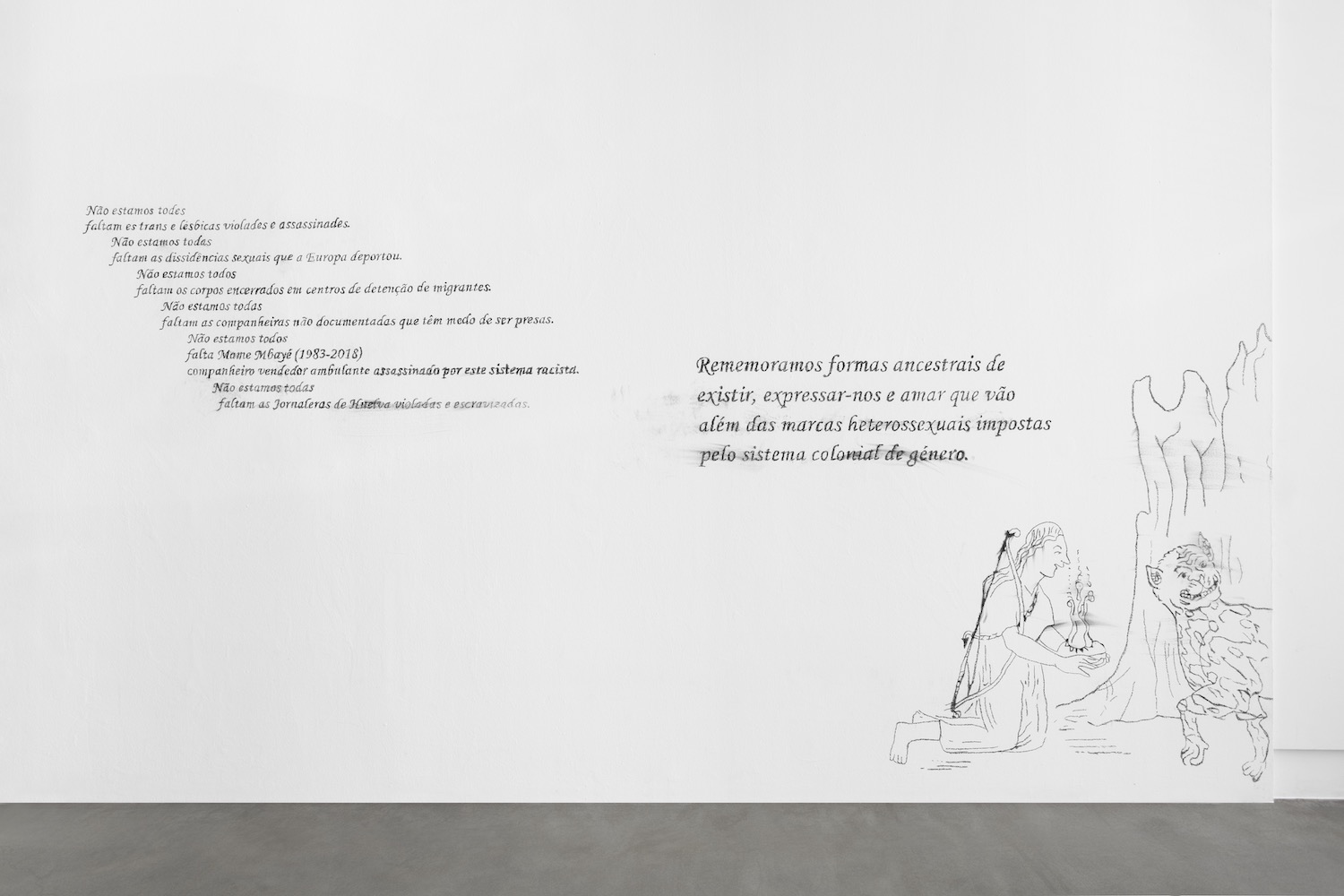

The first encountered work in the Lisbon gallery is Ações de rua, políticas e estéticas ancestrais (2014–2023), a site-specific installation by Colectivo Ayllu/Migrantes Transgresorxs that forms an archive of some of their street actions to date. Several large-scale banners document the Latin America-born Spain-based collective’s decolonising fight for emancipation from heteronormativity. The pieces are suspended from the ceiling following a triangular huaca design—an ancestral architectural pattern from the Andes which traditionally represents an object of reverence. Positioning their posters of activism in this way, Colectivo Ayllu creates a veneration for their queer decolonial protests and workshops, successfully bringing collective street protests into the museum in a way that encourages organised action. The installation is completed by the video installation Beautiful Creatures (2019), showing what the collective calls "Critical Pride": a protest for rights for queer people of colour. The video is empowering and joyful to watch—something that is directly countered by the words chalked on the wall stating that we are no longer all present—não estamos todes, as the violated, assassinated, detained and deported are not there to join the joyful protest.[7] This careful balancing between collective empowerment and critical remembrance persists throughout Emancipação do Vivente, in a simultaneous recognition of systematic injustice and the possibility of emancipatory change.

Two works, one in each of the galleries, draw connections beyond the European continent: Raquel Lima’s video and poetry installation in Lisbon and Dima Mabsout’s multimedia installation in Almada. Showcased in writing on the wall and read in combination with meditative breathing over the video of a waterfall filmed in São Tomé e Príncipe, Lima’s O Meu Útero Não Está na Europa (2023) reformulates migratory displacement that introduces the idea of the uterus as a place for intergenerational memories to be healed—beyond the rationalisations of the mind and the vocal expressions of resistance.[8] Creating a meditative healing space through video, audio and writing, further activated at the opening with a performance by the artist, the work draws on multiple colonial histories of early slave emancipation via the birth of the next generation; current race inequalities in healthcare specifically in connection to the uterus; the prevalence of waterfalls in São Tomé e Príncipe, where Lima lives, as well as spiritual understandings of the waterfall as a locus of beginnings.[9]

On the other side of the river, Mabsout’s Humbaba’s Womb: Mythologies of Fear (2022–2023) is parallel to Lima’s piece even by title, albeit using the synonym—womb instead of uterus—reserved for the time during pregnancy. In contrast to Lima’s metaphysical investigation of the waterfall, Mabsout investigates the illegal sand extraction in her homeland Lebanon and the dried leaves, stones, sticks and pigments in Portugal. Through a multitude of drawings, sculptures and found natural objects, including a display of the strength of natural pigments of the land, Humbaba’s Womb speaks to the resisting and powerful force of the land; three mythical poems written on the walls that tell a colonial story of conquest through a dialogue that circles an egg held and then dropped. One of the poems, entitled Confrontation, speaks to the wider discourse on the bottom floor of the Almada exhibition, related to the emancipatory possibilities of nature itself: "It can be easy to blame ourselves, / as monsters destroying her soils, / to forget sometimes, / that the slightest shift in her sleep is / an earthquake wiping out cities built by / our biggest machines."

Within this space of exploration of soil as a living body of memory with a past, a present and a future is Filipa César’s film essay Mined Soil (2012–2014), screened in the same room. It focuses on a dual timeline of Amílcar Cabral—the agronomist, intellectual and revolutionary leader campaigning for the emancipation of Portuguese-controlled Africa who in the 1950s was researching soil erosion in Alentejo on the one hand, and the current gold mine that is extracted in that very place on the other. One of only two previously existing works not involving site-specific compilation or documentation, it is in this respect mirrored in the Lisbon gallery by Alfredo Jaar’s 1992 (1992): a light-boxed photograph of the barbed-wired wall of Europe, protecting its borders from migrants in a stark reminder of Europe’s ongoing violence against displaced peoples that ties the Lisbon part of the show together.

Finally, Frame Colectivo’s second piece calibragem (2023) presents a text and video installation created from excerpts of the collective’s ongoing project that gathers motorway journey videos which "highlight eurocentric and nationalist narratives embedded in landscapes,"[10] this time showcasing a motorway in Lisbon coloured by the Estado Novo buildings set in contrast to a drive between Luxembourg and Antwerp, where the urban landscape shows the richest and most energy-consuming motorway network in Europe, drawing on Belgium’s colonial past.

Bringing together these various, multiple and diverse emancipatory acts of resistance to displacement, Emancipação do Vivente carefully balances between knowledge-power and hope-activism. The exhibition as a whole has a stark sense of resistance empowerment, while giving ample space to each installation’s depth of research and specificity. In fact, Mf D’s very contextualisation of the disparate pieces across two rather small spaces vis-à-vis one another makes visible the global power structure of the "dis place/ment" that pervades across groups, borders, species and elements.

Museum for the Displaced (Mf D)

Maria Kruglyak is a researcher, critic and writer specializing in contemporary art and culture. She is editor-in-chief and founder of Culturala, a networked art and cultural theory magazine that experiments with a direct and accessible language for contemporary art. She holds an MA in Art History from SOAS, University of London, where she focused on contemporary art from East and South East Asia. She completed a curatorial and editorial internship at MAAT in 2022 and currently works as a freelance art writer.

Proofreading: Diogo Montenegro

Emancipação do Vivente. Exhibition views Galeria da Boavista; 2023. Photos: © Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of Galerias Municipais de Lisboa.

Emancipação do Vivente. Exhibtion views Galeria Municipal de Arte de Almada. 2023. Photos: © Patricia Black. Courtesy of Museum for the Displaced.

Notes:

[1] "Museum for the Displaced: Conversation between Yvette Mutumba, Ana Sophie Salazar, Mohammad Golabi, and Leong Min Yu Samantha," Stedelijk Studies Journal 12 (23 January, 2023): stedelijkstudies.com/journal/museum-for-the-displaced-interview/.

[2] The exhibition participants are predominantly collectives or solo artists working collectively and in collaboration with communities and other artists on research-based projects actively striving for change.

[3] Emancipação do Vivente exhibition brochure.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ana Naomi de Sousa, "Portugal’s worsening housing crisis hits a diverse neighbourhood," Al Jazeera (5 April 2023): aljazeera.com/news/2023/4/5/portugals-worsening-housing-crisis-hits-a-diverse-neighbourhood.

[6] As ETC succinctly put it in a social media post from 13 March 2023: "In the same area : 2 lithium mining projects, 5 dams, 3 wind farms, 2 floating photovoltaic power stations, high-voltages lines, 6 agricultural colonies… and 3 endangered species. What future does all this hold for #barroso ?" instagram.com/p/CpvjdNHMIn9/.

[7] "Não estamos todes / faltam es trans e lesbicas violades e assassinades. / Não estamos todas / faltam as dissidências sexuais que a Europa deportou. / Não estamos todos / faltam os corpos encerrados em centro de detenção de migrantes." Excerpt of the first lines in Colectivo Ayllu, Ações de rua, políticas e estéticas ancestrais.

[8] The head rationalises, the voice expresses, but it is the uterus that holds the memories. Hence some wombs silently scream what others would say if they had not been historically silenced. // But all carry the memory that a day is not a measure of time, just as a waterfall is not a measure of space. … And if millennial waters always fall for the first time in a waterfall, the uterine waters, the ones that brought us here, are likely to be located, healed, and signified for the first time, again and again…" Excerpt from the English version Raquel Lima’s introductory text to O Meu Útero Não Está na Europa.

[9] In conversation with Raquel Lima, I discover that in her academic research work in orature, slavery and Afro-diasporic movements, she investigates TAFUA, songs of slavery between Angola and São Tomé. It is these songs that we find in the video installation and that the artist also sang during the performance at the exhibition opening. The theme of the uterus is instead part of Lima’s artistic research, dealing with the tension between uterine health and colonialism through several references such as the 1871 law in Brazil, The Law of the Free Womb / Lei do Ventre Livre, which stated that children of enslaved women would be born free. The law was widespread across Latin America.

[10] Emancipação do Vivente exhibition brochure.